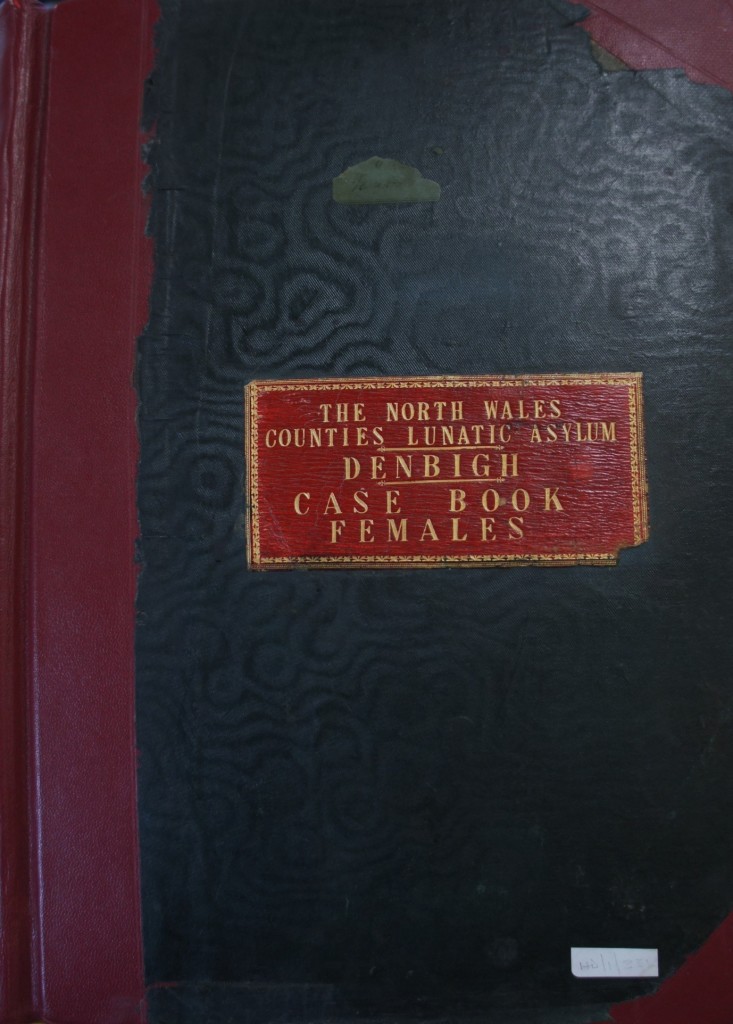

When Dr William Williams took up his post as Medical Superintendent in January 1875 the North Wales Lunatic Asylum was almost full, with 394 of its 400 beds occupied. And of these patients less than 10 per cent were thought likely to recover.

Despite this gloomy forecast the 29 year old Dr Williams would have found the asylum looking its best with Christmas decorations still in place and preparations well underway for the customary annual ball to be held on January 8th attended by patients, asylum officials, attendants, and local dignitaries (see also ‘Music: Entertainment and Therapy’). A staff ball for more than 200 people was held the following week when, according to a local newspaper report, dancing continued until 2 am and “a Christmas tree shone radiant with niceties which will be distributed to the patients”.[1]

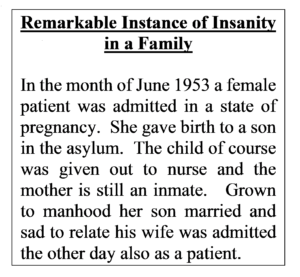

The readership of the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, the North Wales Chronicle and the North Wales Times clearly took an interest in the affairs of the asylum. Announcements and reports of social events and entertainments appeared frequently and annual general meetings were always covered in great detail. But the papers also carried short paragraphs like the one below[2], reported in the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, on 30th January 1875, which were thought to be of general interest to readers:

What will become apparent over time are the tensions between the press and institutional interests. Even in the 19th century – long before the age of ‘spin’ – asylum officials were keen to ensure that the press only published information which they thought cast the institution in a good light.

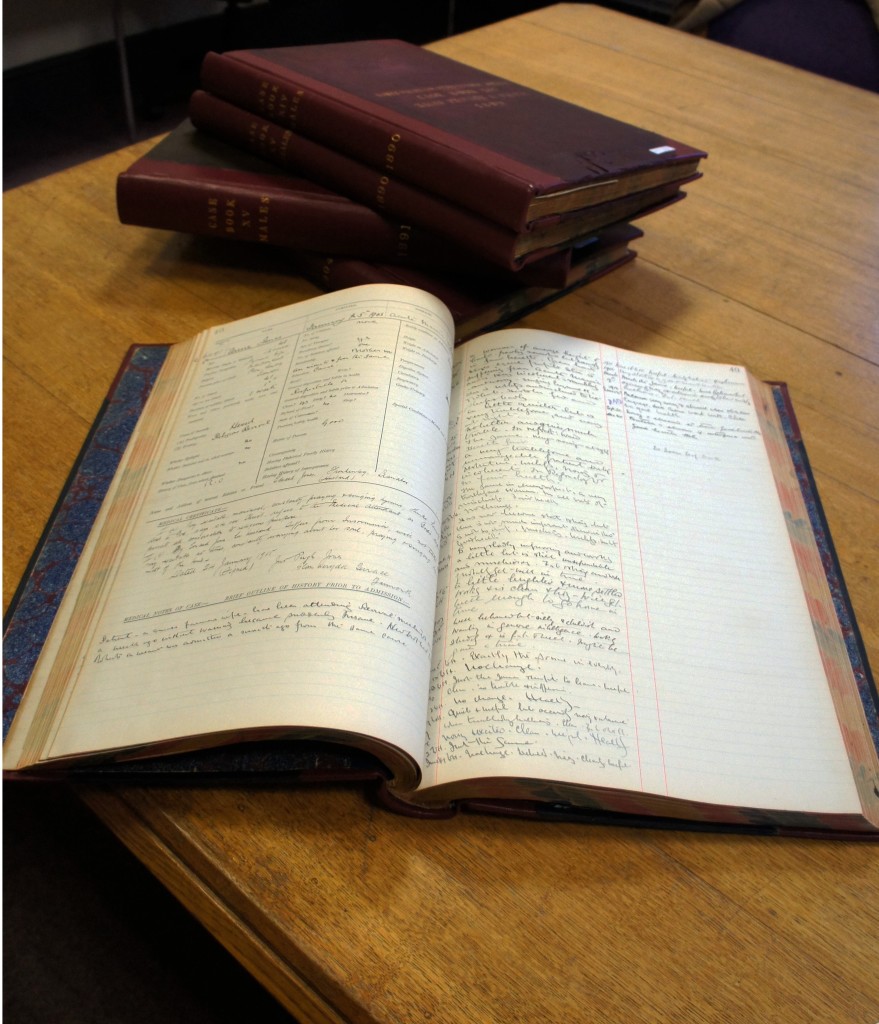

One of Dr Williams’ first objectives was to introduce new case books so that detailed information about family circumstances, employment and physical health could be recorded for each patient as well as the progress they made in the asylum.

The 1875 case notes are probably the richest of the 50 years of notes which have been collected. There would have been a will to make the new scheme successful and, although the asylum was already operating at full capacity, the situation at this stage was manageable. There was time for the medical superintendent to see each new patient regularly and for the clerk to write up detailed notes. These early cases give a good idea of the medications and treatments at Dr Williams’ disposal. In 1875 any drugs dispensed to patients were carefully recorded but in later years, as the asylum steadily filled up, there may have been less time available for such meticulous note taking. Certainly the case notes after 1890 appear to contain less detail in this respect.

Chloral Hydrate was commonly administered as a sedative and more than half of the 56 patients admitted from North West Wales in 1875 were prescribed a Chloral draught either as a general sedative or as a nightly draught. Castor oil, croton oil, turpentine and powdered jalap were employed as purgatives; opium, chalk and sulphuric acid as remedies for diarrhoea; quinine and iron as tonics; ammonium carbonate with squill or snakeroot as expectorants and dilute prussic acid to treat vomiting. A variety of ointments and lotions including calomel (mercurous chloride), zinc, lead, iodine and sulphur were employed to relieve skin diseases, wounds and ulcers. And at this time poultices and plasters remained a favoured treatment for superficial and deep-seated inflammation – linseed meal poultices for skin conditions such as erysipelas and a mustard plaster (synapism) or a lytta (‘Spanish Fly’) plaster to cause blistering in cases of pleurisy and pneumonia. The bill for drugs in 1875 amounted to £45 5s 8d and for surgical instruments £13 10s. The bill for wine, spirits and porter – still the basics of the therapeutic armoury in 1875 – was higher!

Restraint would have been a last resort and, according to the Annual Report, no restraint was used at all in 1875. But the case notes indicate that the padded room, the tick dress and strict one-to-one supervision were all part of the treatment regime for patients considered to be ‘refractory’.

A breakdown of the retrospective diagnoses of the 56 patients who were admitted to the asylum is shown in Table 1 below:

1875 Asylum Admissions: Current diagnoses

| Diagnosis | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Dementias | 3 | 3 |

| Organic disorders | 3 | 5 |

| Alcohol related disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Schizophrenia | 5 | 7 |

| Delusional disorder | 0 | 1 |

| Acute and transient psychosis | 2 | 1 |

| Manic episode | 1 | 0 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 1 | 2 |

| Depressive episode | 5 | 2 |

| Post partum disorder | 0 | 1 |

| Neurotic disorder | 1 | 1 |

| Personality disorder | 1 | 1 |

| Mental handicap | 0 | 2 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 0 |

| General paralysis of the insane | 3 | 0 |

| Insufficient data (no case notes) | 3 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 30 | 26 |

Dr Williams would see most of his new patients the day after admission and regularly afterwards until an improvement was seen. Routine examinations would then be gradually reduced and chronic patients might be seen by the Medical Superintendent or his assistant every six months, sometimes only once a year, unless there was a sudden deterioration in their condition or the onset of a physical illness.

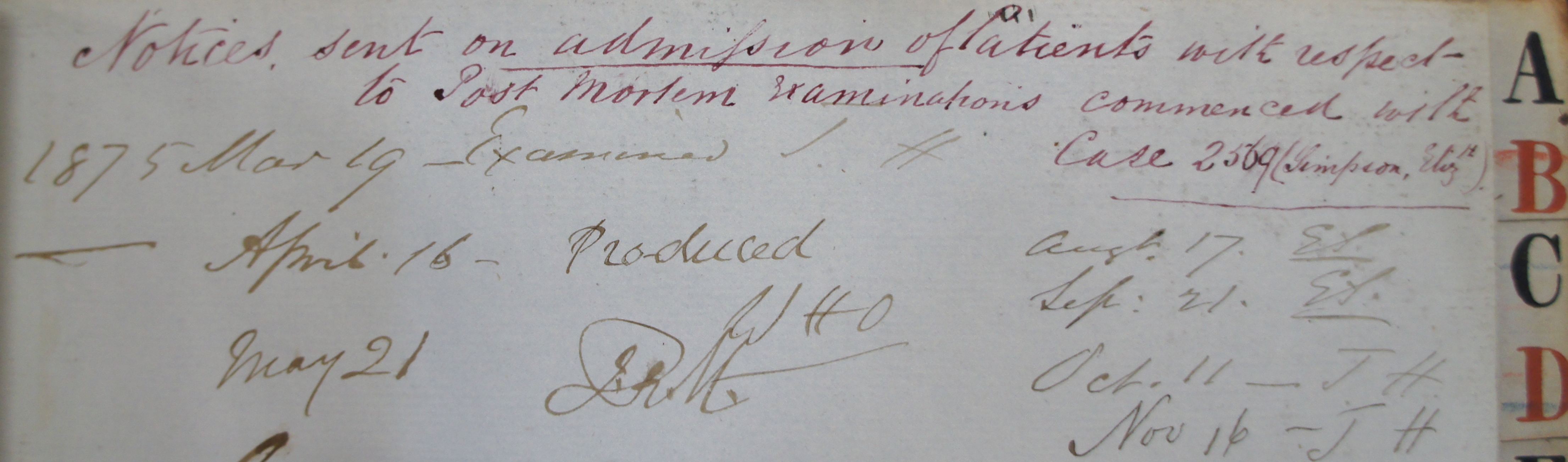

The 1875 case books indicate that Dr Williams took seriously his predecessor’s concerns about the small number of post mortems conducted at the asylum because of an unwillingness of relatives to consent and devised a new system, adopted the following year, where admission would be subject to consent to post mortem examinations. It is noted on the first page of the female case book that: “Notices sent on admission of patients with respect to Post Mortem examinations commenced with Case 2569 (Elizabeth Simpson of Wrexham, admitted May 1876)”.[3]

Poor Law officers continued to send an ‘unfavourable’ class of patients to the asylum for subsidised treatment at the asylum rather than care for them in the workhouse hospitals so that Dr Williams’ first year was clouded by having to deal with an unusually large number of deaths. 54 patients died in 1875 and 30 of these had been in the asylum less than twelve months, 14 less than six months. However, Dr Williams was keen to stress that government policy was not the only reason for the deaths, as a larger number of old and feeble patients were being admitted than in the earlier years of the asylum:

At that time there was a prejudice against Asylums; but the kind and efficient manner in which my predecessor managed this Institution for a lengthened period, dispelled that feeling, and relations at the present time do not make the same efforts as formerly to keep their friends at their homes. On the contrary, as illustrated in the case of one of the females … the reason for sending her, in the serious condition she was in, was, that her friends thought she would receive more unremitting Medical attendance here than they could procure for her at her own home.[4]

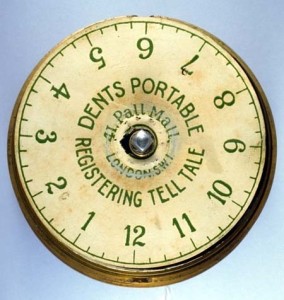

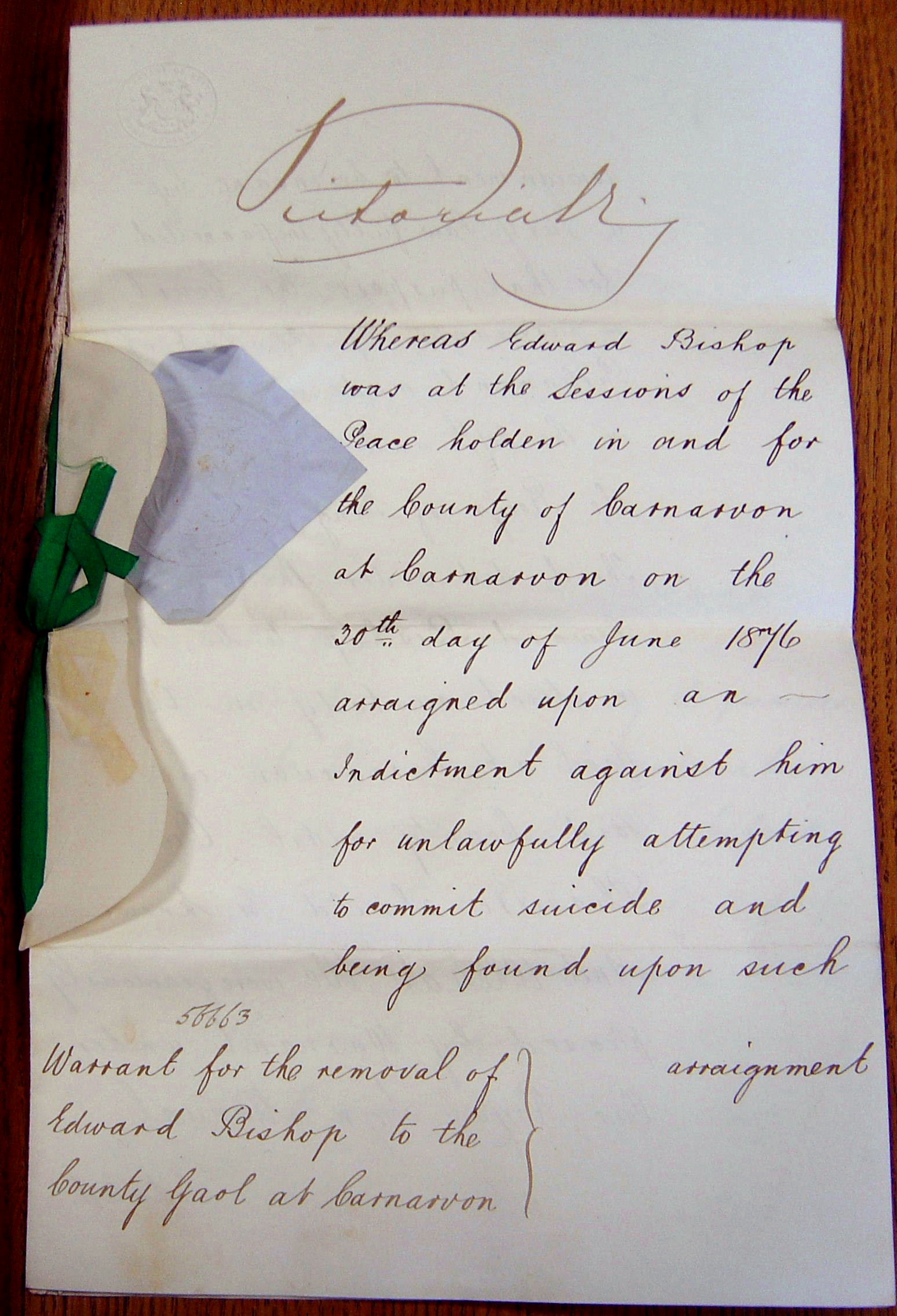

Forty patients thought about or attempted suicide in 1875 and the Commissioners in Lunacy noted in June of that year that, despite their earlier recommendations, nothing had been done to implement the continuous supervision at night of suicidal (and epileptic) patients. Although it proved impossible for special wards to be organised for this purpose, Dr Williams was able to report in January 1876 that Dent’s Tell Tale Clocks had been bought to register the work of the night attendants, presumably to make sure that patients thought to be at risk were regularly and carefully observed.

Under the paper disc a carbon and a second disc. Small glazed window in the cover to reveal the hour and a slot to allow an impression to be made on the disc.

Substantial brass casing and leather protective pouch with apertures for the window and slot. Patented 1862.

Whether or not because of the tell-tale clocks there were no successful suicides in 1875, in spite of a few determined attempts by hanging. But Dr Williams had to deal with a fatal accident in July of that year when a male patient removed the head gear from a horse in a cart to enable it to eat hay. The horse took fright and bolted and, in trying to stop it, the patient was run over and died within half an hour of the injuries he sustained. An inquest returned a verdict of accidental death with no blame attached to anyone.

The accident occurred after the Commissioners had made their inspection and so it did not appear in their June report. Nor did the case of smallpox which occurred in September. The male patient concerned did not live in North West Wales and so details of his treatment have not been recorded here but Dr Williams reported that he was “isolated as thoroughly as the structural arrangements of the Asylum enabled” and that this along with “other precautions” prevented any spread of the disease.[5] It could not have been easy, given the overcrowded condition of the asylum, to keep news of the man’s illness from his fellow patients and fears of an epidemic may have been widespread.

What the Commissioners were able to report was that the patients appeared clean and well cared for. The women were wearing print dresses of good quality and although only a third of the men had Sunday suits in 1875 it was hoped that a large number would have them before much longer. The pea soup, with ‘a certain amount of meat in it’, which constituted dinner on the day of their inspection, was very good. All in all they had nothing special to report about the condition of the patients besides noting that conduct of the men was better than that of the women. While there was some disorder in the female ward, in the corresponding male ward the patients were found quiet and well behaved.

Dr Evan Powell, who had acted as Medical Superintendent during Dr Turner Jones’ illness, resigned his post as Assistant Medical Officer shortly after Dr Williams took up his post[6] and Dr Lloyd Ellis was appointed in his place. But Dr Ellis left after just six months and was replaced in October 1875 by Dr George Miles whose appointment was somewhat problematic because he spoke no Welsh. This was an essential qualification for the post but, since there had been no applications from Welsh speakers, it was decided to appoint Dr Miles pro temp and reconsider the rule requiring “colloquial knowledge of the Welsh language” at the next annual general meeting.

One of the first patients Dr Williams would have seen and the first patient from North West Wales whose admission was detailed in the new case books was Jeremiah Owen (2424), a copper miner working at Mynydd Parys near Amlwch, who was brought the 70 miles from Anglesey to Denbigh in manacles on 28th January 1875. When he was examined Jeremiah was not thought to be dangerous – even though his medical certificate suggests his mother had good reason to think that he might be!

After dominating the world copper market in 1780 the Parys mines were producing poor yields of ore by 1875 and men were being laid off, although it seems Jeremiah preferred to blame his mother for his worries about employment as well as the troubles he experienced during his time in both America and Yorkshire and disagreements he’d had with fellow members of his Calvinist Methodist chapel.

Jeremiah Owen’s case is a particularly interesting one because it introduces three themes which reappear in the case notes throughout the 19th century and beyond –concerns about work, emigration to the Americas and religious revivalism.

Strikes and scanty wages

Although copper was mined in Snowdonia for centuries it did not represent a major source of employment outside Amlwch and copper miners like Jeremiah accounted for only two of the recorded admissions to the asylum. It was the slate industry which dominated the economy of North West Wales during the second half of the 19th century with Bethesda and Llanberis having the two largest slate quarries in the world (Penrhyn and Dinorwig) and Blaenau Ffestiniog the largest slate mine. So although not proportionally over-represented quarrymen and slate miners form a significant group of asylum patients. [7] (See ‘Quarrymen and Insanity’ by Pamela Michael).

Ten per cent of the male patients admitted in 1875 were slate workers. One of them was Thomas Morris of Bethesda (2441), admitted on 16th April with melancholia after attempting to cut his throat with a pair of scissors. Thomas Morris believed that his neighbours and fellow workmen were ‘against him’ and it is possible he had good grounds for thinking this because he was one of the few Penrhyn quarrymen who had kept on working during a strike of the previous year aimed at founding a trade union. In October 1874 the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald described an air of desolation at the quarry where:

In place of 3000 men swarming about the galleries there are now but 30, chiefly old men for whom the pomps and vanities of trade unionism have had no charm and who, having worked in the quarry for 40 or 50 years, evidently mean to die in harness.

And it would have been during this action that Thomas, ‘greatly annoyed’ by the striking workmen, had shown the first symptoms of insanity. The strike lasted 16 weeks and resulted in the formation of the first quarrymen’s union. A report on the ‘happy termination’ of the strike which appeared in the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald in November 1874 gives a clue to how a bradwyr (blackleg, traitor) like Thomas might have been made to feel in the aftermath:

The few who remained at work were in no way molested, nor was there even a show of interference or yet of bad feeling towards them in the use of language or gesture. But these men are and have been held in supreme contempt; and last Saturday night…the pent up indignation for the first time found vent but only in murmurings loud and deep.

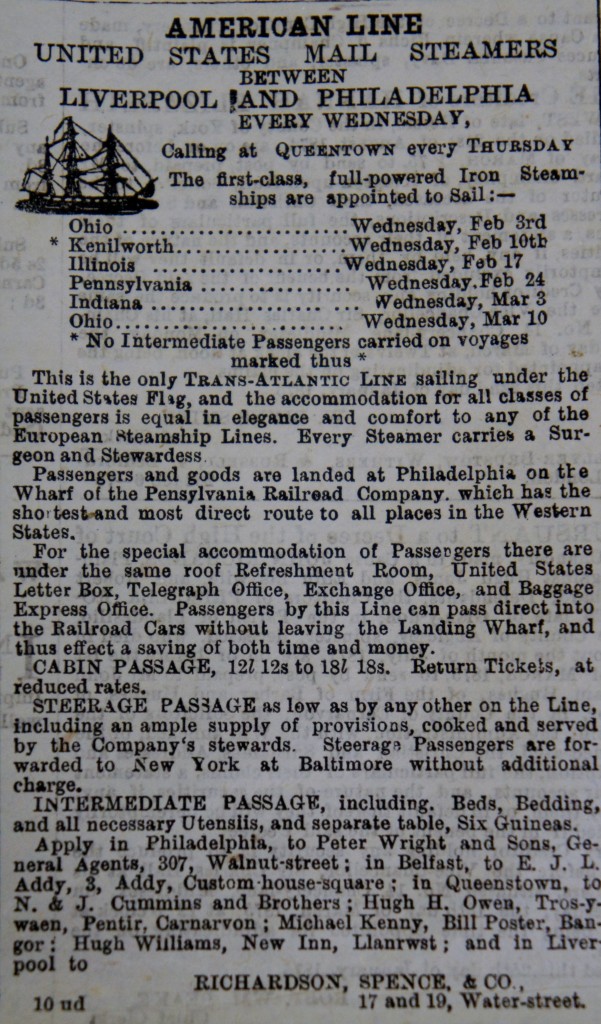

Steerage to a better life?

Jeremiah Owen’s anxieties about employment, in the face of declining copper yields, may have underpinned his emigration to America. However, most of the Welsh emigrants were farmers who settled in Ohio, colliers from South Wales who headed for Pennsylvania and then in the latter half of the 19th century quarrymen and miners from North Wales were drawn to the ‘Slate Valley’ regions of Vermont and New York. Local newspapers regularly carried advertisements for steerage passage on the United States mail steamers which left Liverpool several times a week.

Clearly Jeremiah Owen’s experience in America did not live up to expectations and his family and neighbours thought he had not been sane in the two years since his return. The 19th century asylum case notes indicate that his was not an isolated case.

Howell Evans had gone to America as a colonist and built up a good farm but when he fell out with his wife and she left him he became insane and spent eighteen months in an asylum there. After being discharged he found that all his property had gone and so he was forced to come home to Tremadoc and work as a farm labourer. Just before his admission to Denbigh in April 1876 his wife had offered to rejoin him and ‘brooding over the expense of her passage’ is offered as a cause for his relapse, although regular attendance at religious revival meetings was also thought to have contributed.[8]

It’s fair to say that the emigrants who turn up in the asylum records represent the most negative aspects of trying to make a new life thousands of miles away from home and that for many others the decision to leave North Wales was a good one. Perhaps if Joseph Jones, a quarryman at Festiniog who had been earning ‘but scanty wages’ for some time because of a depression in the slate trade, had managed to save enough to emigrate to America with his family in 1884 he would never have become melancholic. A concert held to raise the money needed for his passage did not even clear enough to cover its expenses and a week or two later Joseph became low spirited and suicidal thinking of little else but ‘that his family and self will have to go to the Workhouse or starve’.[9] By the time he was discharged less than two months later he had given up all idea of going to America.

It may not have been the desire for higher wages and a better life that prompted Richard Williams to emigrate but rather the wish to rid himself of his wife. He had deserted his wife, gone to America and later returned to Conwy. Some years later he was admitted to Denbigh with a delusional disorder manifested by the unshakeable belief that he was destined to marry a Miss Ellis. His existing wife would not be a problem, he told the Medical Superintendent. His first marriage had been a marriage of convenience and could be ended at any time while the ‘law of God’ had made Miss Ellis his wife. The case notes suggest that Richard Williams, ‘highly erotic and decidedly dangerous to females’ had already been prosecuted twice for ‘molesting’ Miss Ellis but so determined was he to marry her that he asked Dr Williams to be his best man.[10]

Anne Jones of Bryngwran had also been deserted for America although it became apparent that her husband had no long term plans to cast her off. After hearing nothing of him for a period of ten years, she concluded he was dead and remarried. But while she was living with her second husband, Anne’s first husband returned and the ‘mental shock’ of his reappearance is given as the cause of her first episode of insanity.[11] We must assume that Anne renounced her bigamous relationship with Mr. Jones because when she was admitted again in 1889, her name is given as Anne Roberts. Now 75 years old and in poor circumstances she had been taken to Valley Workhouse after being found ‘wandering at large and running after her husband with a spade going to kill him’. She died in the asylum from pneumonia in 1892.

Jane Owen (2464) who ‘threw herself away when she got married’ and had never been perfectly sane since, may have been delighted for her husband to take himself off to America without her! She had been a private patient at the asylum a few years earlier but in 1875 ‘marrying an old man’ was given as the cause of her mania. Richard Owen, a farmer, was 25 years older than Jane and her symptoms – an unwillingness to go to bed, tying her dress fast around her legs and pushing her underclothing into her vagina, feeling herself to be on fire – may go some way towards explaining why this was given as a cause of her insanity. There is a suggestion that when this patient was examined on admission she was investigated for diabetes since it is recorded that, despite slight emaciation and very copious urine, there was an ‘absence of albumen and sugar’. By the early 19th century chemical tests had been devised to detect excess sugar in the urine and it can be seen that diabetes was rare amongst admitted patients and that very few patients with a serious mental illness went on to develop the disease during their time at the asylum. (For further details see Le Noury et al 2008).

Preaching, singing and the ‘sinfulness of dancing’

In 19th century Wales the nonconformist chapel was becoming the centre of social as well as religious life and Jeremiah Owen’s case provides a good illustration of this. Eloquent preachers attracted growing congregations to new and ever larger chapels where, in addition to Sunday worship and evening prayer meetings there were lectures, cultural meetings, singing and preaching festivals. But, however large their congregations, fears remained that the radical evangelical message of Welsh non-conformity might lose its direction. So from the middle of the century a succession of religious revivals where the faithful were called upon to testify to being ‘chosen’ for salvation through public demonstrations of belief generated intense spiritual experiences. And falling out with chapel elders was more than a religious concern because, so central was chapel to the life of the community, it was a social disaster too. Jeremiah Owen’s belief that the Chapel people had treated him unfairly and were ‘setting upon him’ seems to have made a major contribution to his severe depression.

John Williams (2428), an agricultural labourer from Llandwrog near Caernarfon, was ‘full of religious ideas’ when he was admitted to Denbigh in February 1875 with acute mania and he spent much of his time there engaged in reading the bible and arguing ‘very reasonably’ with another patient about the sinfulness of dancing!

John Jones (2465) was a shoemaker by trade but also a Calvinist Methodist preacher with ambitions to qualify for the ministry. He had been preparing hard for entry examinations to Bala College – too hard it seems because he gave up at the last moment and overstudy is given as the cause of his insanity in June 1875. This patient’s reception order gives an indication of how parish clergy might be involved in certifying pauper lunatics and, in this particular case, how burdensome they might find the task. Unable to answer questions relating to epilepsy and suicidality, ‘the officiating clergyman of the parish of Llanerchymedd Hugh Owen’, has written on the reverse of the order:

“It is not part of my duty to fill up these forms and I did not fill this up beyond what was required of me as the Clergyman of the Parish. I therefore hope that no more trouble will be caused me about them”.

Even before the great revival of 1905 (see also If everybody went crazy), when there was a significant increase in admissions for brief polymorphic psychoses the vast majority of which were associated with revival meetings[12], religious concerns were thought to be responsible for many of the admissions to Denbigh. In 1875 a religious element can be identified in the case notes of eleven patients, representing almost 20 per cent of admissions .

Mad in March, sad in September

In June 1875 Ann Hughes (2462) of Llysfaen, a flourishing limestone quarrying village near Colwyn Bay, became a patient for the third time. Ann’s psychiatric career spanned 28 years and 14 asylum admissions until she died at the asylum in 1901 from congestion of the lungs. From her case notes, it is possible to trace not only the the course of her illness but also its effects upon family and friends. A fearsome foul-mouthed woman when she was ill, violent and suspicious of everyone around her, she could inspire great affection when she was well so that Dr Cox described her in 1898 as ‘a wonderful old woman in every way’.[13]

There is some evidence that Ann enjoyed a trusting relationship with her local clergyman because prior to her fourth committal in 1876 she had apparently ‘told the clergyman she felt herself getting ill and would have to be sent back to the asylum’.[14]

And in 1880 we learn that Ann was employed as a housekeeper by the Rev Jones at Llysfaen. This may have represented an attempt by the minister to support and rehabilitate her, a practice perhaps not uncommon at the time. In Caradog Pritchard’s semi-autobiographical novel Un Nos Ola Leuad (One Moonlit Night) the boy narrator describes going to the vicarage after school ‘to help Mam with the washing’. The boy’s mother was, like Ann Hughes, a widow, a laundress and a patient at Denbigh Asylum.

Ann’s case notes are remarkable for the insight they offer into the progress of her illness, the character of which was most clearly indicated in 1880. Noisy and mischievous in March, by September she was observed to be ‘rather despondent, cannot sew even, sits dreamily with sewing in her hands, voice feeble and high pitched’. And from1886 Ann was no longer diagnosed with mania as before but melancholia characterised by ‘a great restlessness and depression of mind, almost total sleeplessness’. Her son, Henry, reported that his mother would not stay in bed at night and had been found about a mile from home on her way to the sea. For the first time, Ann was thought to be suicidal.

Henry Hughes and his wife were caring and supportive throughout a long series of relapses, bringing Ann home to live with them when she became low spirited and taking time away from work to look after her. But in 1892 Henry was forced to admit that he was no longer able to care for his mother and asked that she be removed to some place of control. Ann once more recovered and pronounced ‘quite fit to be at home had she one to go to, but it seems she has not’.[15] Although it is possible that Henry and/or his wife had died by this time it seems more likely that they no longer felt able to take responsibility for the old lady, whose condition was still fluctuating between depression and exaltation.

These case notes indicate that the revolving door analogy often applied to modern acute psychiatric units also applied throughout the period North West Wales was served by Denbigh Asylum. Patients like Ann Hughes, retrospectively diagnosed with bipolar disorder, had anything up to 19 admissions and it has been possible to construct similar psychiatric histories for several of these patients. Between 1875 and 1924 134 individuals shared 430 asylum admissions, an average of three admissions each, with two thirds of these patients admitted for the first time with a manic episode.

This is presumably explained by the greater difficulties manic behaviours would have presented for the patient’s family and community compared with a withdrawal into melancholia. It was perhaps only when a suicide risk was identified that hospital treatment was considered necessary for melancholic patients. The incidence of bipolar disorder has remained fairly constant from the 19th century until the present day (see Healy, 2011 ‘Mania: A short history of bipolar disorder’ Chapter 1, Chapter 2 & Chapter 3) – and, in this respect, it contrasts markedly with schizophrenia which arguably saw a dramatic increase during the 19th century [16] and appears to have fallen in incidence over recent years (Healy et al, 2012).

‘Enceinte’ and a long way from home

Maria O’Brien (2454), a 24 year old domestic servant, was admitted in May 1875 with puerperal mania and her case does much to reveal the economic and sexual vulnerability of women in the 19th century which has been documented in detail by the social historian Lionel Rose.[17] Maria was turned out of her situation in Manchester after finding herself pregnant and in her desperation to find her way home to Co. Sligo, she walked more than 120 miles from Manchester to Holyhead. Her child was delivered at Valley Workhouse but three weeks later Maria was admitted to Denbigh Asylum after she had been found trying to hang herself at Holyhead railway station. If she became pregnant, commonly through a relationship with a male servant but sometimes their employer, a domestic servant would be instantly dismissed without references leaving her homeless and penniless. Records of inquests held in Gwynedd during the 19th and early 20th centuries suggest that an unwanted pregnancy would adequately explain a suicide attempt. For example a Glasinfryn farmer, when questioned, testified that a young servant who shot herself in the stomach had earlier confessed to him that she was ‘in trouble since she came from service in London’.[18]

Maria has been retrospectively diagnosed with a postpartum disorder and the Denbigh case notes support a strong association with suicide. Two of the 101 post partum patients in the 50 year sample committed suicide within a week of their discharge – the highest suicide rate of any diagnostic group admitted to the asylum.

The case of Catherine Jones, a farmer’s wife from Llanllyfni who was transferred to Denbigh Asylum from Broadmoor in July 1879, also suggests a link between postpartum illness and infanticide. Catherine’s Broadmoor case notes and correspondence have made it possible to build up a fascinating story of the way her family and neighbours tried to deal with her illness before she killed her 18 month old baby. They outline the difficulties she experienced of caring for a monoglot Welsh speaker so far from home which in turn were compounded by the arrival of another baby in Broadmoor. The case notes also describe William Jones’ made strenuous efforts to have his wife transferred to an asylum nearer home and the apparent willingness of neighbours to forgive and accept Catherine back into the Llanllyfni community. We hear no more of her after her discharge from Denbigh. (To read more of Catherine’s story see: A Mind ‘different from the minds of other people’).

However, if the murder of Sarah Jones by her mother makes grim reading, the Gwynedd Coroner’s records contain much grimmer stories of infanticide which may have been caused by postpartum illness but may quite simply have been a practical solution for frightened domestic servants who would otherwise end up in the workhouse or on the streets (see ‘Evil Crime or Desperate Remedy –infanticide’).

Truly ‘asylum’

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the1875 case notes is the shocking insight they provide into the desperately harsh conditions of poor people living in North West Wales in the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

There is the shoemaker who first became insane after losing three of his children to Scarlet Fever;[19] the domestic servant found wandering the streets of Holyhead homeless and suffering from tuberculosis;[20] the iron moulder who lost an eye when struck by a piece of metal at Valley Foundry and went on to develop epilepsy;[21] the Irishman picked up by the police suffering from starvation and exposure who left the asylum ‘quite plump and fat’ a few months later;[22] and the elderly woman who had endured a severe prolapse probably for many years before it was treated with a Smith-Hodge pessary at the asylum. [23] More than a third of the patients admitted in 1875 were stated to be in feeble health. And almost a third of them were thought to be suicidal, 11 having threatened or attempted suicide before their committal. The fear of suicide was commonly a reason for families to have a relative taken to the asylum because, quite apart from the grief it would cause, suicide was illegal and might result in a gaol sentence.[24]

All this lends weight to Dr Williams’s conviction that it was the shelter Denbigh Asylum offered, the regular meals and the medical attendance which accounted in some measure for the willingness of families to hand over the care of their relatives to himself and his colleagues.

But overcrowding was already becoming a pressing issue and in their report the following year the Committee of Visitors warned that:

…the day is fast approaching when either the asylum must be again enlarged or a new Asylum erected, unless the number can be reduced by other means.[25]

Read on ‘1890’.

Footnotes

[1] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, January 23rd 1875

[2] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, January 30th 1875

[3] DRO/HD/1/336/Case no. 2569

[4] 27th Annual Report, Annual Medical Report, p.12

[5] 27th Annual Report, Annual Medical Report, p. 13

[6] Dr Powell appears on the 1876-77 list of members of the Medico-Psychological Association as Assistant Medical Officer at the Kent County Asylum, Barming Heath. He was later appointed Medical Superintendent at the Borough Lunatic Asylum, Nottingham.

[7] Pam Michael (1997), Quarrymen and Insanity in North Wales, Industrial Gwynedd Vol. 2, pp 34-43.

[8] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2552

[9] DRO/HD/1/362/Case no. 3486

[10] DRO/HD/1/365/Case no. 3975

[11] DRO/HD/1/335/Case no. 3738

[12] S. Linden, M. Harris, C. Whitaker and D. Healy (2010) Religion and psychosis: the effects of the Welsh religious revival in 1904-1905, Psychological Medicine, 40, 1317-1323.

[13] DRO/HD/1/338/Case no. 4429

[14] DRO/HD/1/331/Case no. 2622

[15] DRO/HD/1/338/Case no. 4429

[16] Edward H Hare (1999), On the History of Lunacy: The 19th century and after, London: Gabbay.

[17] Lionel Rose (1986), Massacre of the Innocents: Infanticide in Great Britain 1800-1939, London, Boston and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

[18] Caernarvon & Denbigh Herald, 31st July 1913.

[19] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2442

[20] DRO/HD/1/331/Case no. 2452

[21] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2439

[22] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2433

[23] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2435

[24] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2593

[25] 28th Annual Report, Committee of Visitors Report, 1876.