In the 19th century “…the periodic discovery of a baby’s body in the street or river was shrugged off as a grim inevitability”.[1] And if infant life generally was held cheap this was especially true of illegitimate babies.

Infant deaths from homicide were difficult to detect at a time when so many children died from infection or neglect. Even so, from 1863 to 1887, the 0-1s formed 61 per cent of all known homicide victims in England and Wales while they constituted less than 3 per cent of the population.[2] And the greatest number of murdered babies were illegitimate.

The link between illegitimacy and infanticide may have been weaker in the rural districts of North West Wales than in the industrial cities of England. One cause of rural promiscuity was cottage overcrowding, where a lack of family privacy meant that girls were sexually experienced from an early age, and in many rural districts no shame was attached to a premarital pregnancy. In the notorious Blue Books of 1847, the commissioners refer to the difficulty of finding a cottage in North Wales “where some female of the family has not been enceinte before marriage”[3]. Allowing for the likelihood that some of these findings were merely verbatim reports of the prejudiced opinions of local landowners and Anglican clergy, North Wales was included in the Registrar General’s 1890 list of those districts where the percentage of illegitimate children was abnormally high. Numbers of illegitimate births in North Wales between 1891 and 1900 amounted to 59 births in 1000 compared with an average of 42 births per thousand for England and Wales. In Anglesey, between 1894 and 1903 the figure was 81 births per thousand.

By far the main area of employment for single women in 19th century Wales was domestic service – the 1881 census showed that 61 per cent of the 24,010 women living in Carnarvon, Merioneth or Anglesey who declared an occupation were domestic servants [4] – so that this group of women would inevitably be responsible for a high proportion of illegitimate births. And an unwanted pregnancy would spell economic disaster for a servant girl with no other means of support. A pregnant servant would be instantly dismissed without references and might more readily resort to desperate measures to conceal her condition and dispose of her burden than a farm girl.

Domestic servants suspected or known to have killed their newborn babies either by intention or neglect appear in the records of inquests held in Gwynedd between 1885 and 1924. However, because the archive is incomplete, it can be assumed that the records of infanticide it contains represent only a proportion of the infant deaths suspicious enough to invite inquests, and an even smaller proportion of the babies who were murdered or abandoned soon after birth.

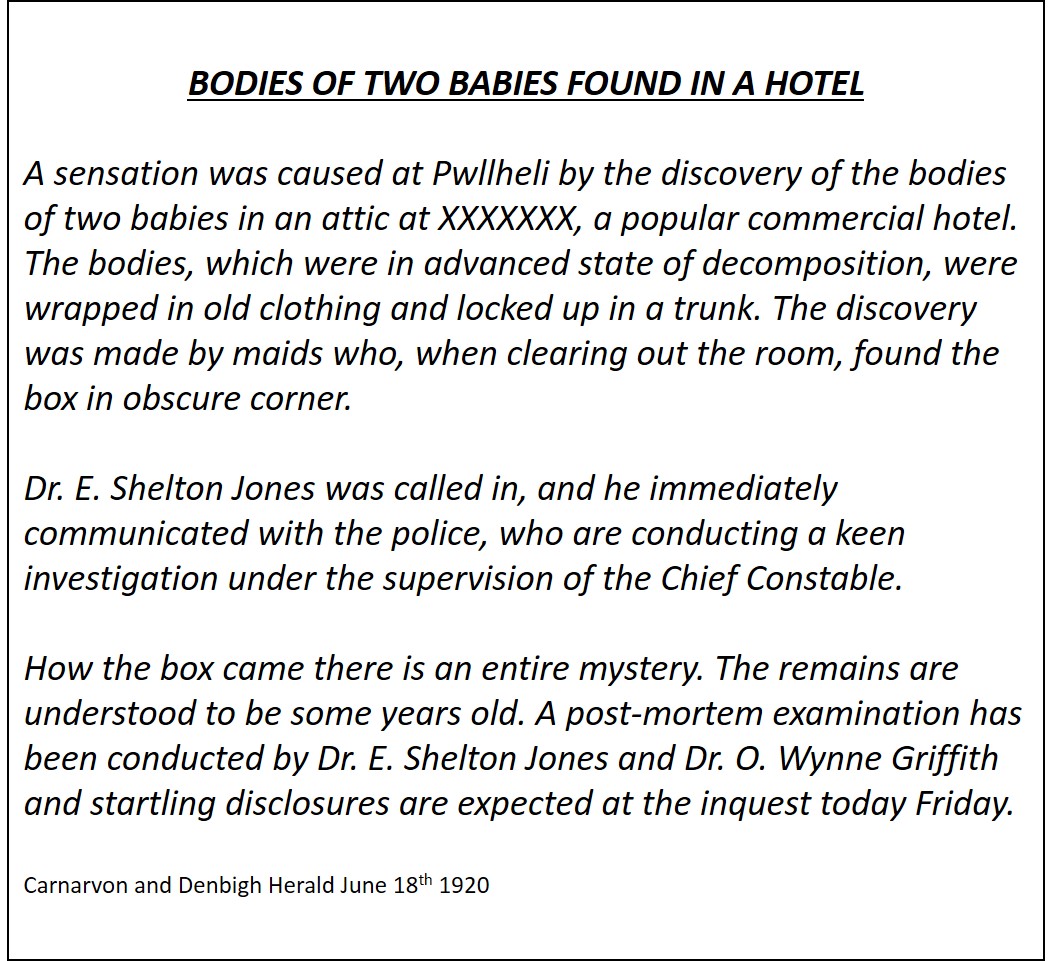

The court room at Pwllheli was crowded for the inquest and some of the women became so excited while the evidence was being given that the Coroner ordered the police to turn them out.

MO, a maid at the White Hall Hotel, was the first witness. She and another maid were clearing out the servants’ attic when, behind a curtained partition, they saw a basket of crockery, a cardboard box and a black tin box. As they removed the box to the middle of the room, they noticed an offensive smell and called for the daughter of the hotel licensee to come up to the attic. Miss MD used an iron bar to open the box and something like a piece of clothing came up with the bar. Dr. Shelton Jones arranged for the box to be removed to the stable.

Supt. G.J.Griffith, Pwllheli, was called to the yard of the hotel where Dr. Shelton Jones directed him to the black tin trunk and told him that he believed it contained human remains. Also in the box were fragments of female clothing and a portion of a newspaper dated 19th September 1915. A black leather satchel contained two penny pieces and a receipt dated 13th October 1915 for £4 13s 6d for a coat, muff and necklace from Pwlldefaid Shop. No name was given on the receipt.

Dr. Shelton Jones testified that the bones in the tin box were those of human beings. He had made a post-mortem examination with Dr. Wynne Griffith, and they had concluded that the bones were those of two children, one having died 18 -24 months previously and the other three years previously. The contents had been disturbed a little but Dr. Shelton Jones could perceive that the bodies had been separately packed. He confirmed they were fully developed to be born alive.

Mrs. WD, licensee of the White Hall Hotel said she had taken possession of the hotel in March 1919. A servant called MG was working there at that time and MG remained in her service for about three weeks after she had taken possession. MG had asked her to do her a favour by allowing her to leave some things there, she had agreed and had given MG assurance that nobody would touch her things. MG had since been back to the hotel on several occasions since then, sometimes assisting for the day.

Both Mrs. WD and Dr. Shelton Jones had been suspicious about MG’s condition about two years earlier. Mrs. LP, the previous licensee of the hotel and more recently proprietor of another hotel in Abersoch, where MG was currently in service, had shared these suspicions. At that time, she had confronted MG who denied she was pregnant.

MG was called to testify and, asked how she had felt when learning that the bodies had been found, said she had not been afraid and that her mind was perfectly at rest when she heard about the babies. She agreed she had left property at the hotel but she denied the black tin box was hers and said she had never seen it before. She also denied buying a coat, muff and necklace in Pwlldefaid Shop in 1915 although she agreed she had been a customer there on several occasions. Shown the black handbag, she denied it was her property. She also denied being in a “certain condition” in 1916.

The Coroner in summing up, said that the jury should dismiss all statements made outside the court and consider the evidence given on oath – which was very conflicting. It was impossible to say by whose hand the children had died. A verdict was given that there was no evidence to prove how, when, or by whom the bodies were placed in the box and no evidence to prove a cause of death.[6]

Drawn to the sheepfold by his dog he found a body

A verdict of ‘death by natural causes’ was given in the case of a newborn baby boy found in a dilapidated sheep fold on Moeltryfan Mountain on 15th September 1900. KJ was already pregnant at Whitsuntide when she went into service with an elderly couple who ran a smallholding near Llanwnda but they did not suspect her condition. A native of Anglesey, the young woman was a stranger to them when their daughter, who was living on the island, told them of her need for a place.

KJ was missed from the house on the afternoon of the 15th September. Some neighbours went onto the mountain to search for her and, after 2 or 3 hours, she was found in an exhausted condition in an old sheep fold. Known to be ‘subject to fits’ she was taken home and put to bed. The following day WJW, a quarryman and farmer who lived close by, was attracted to the place by his dog and there he found the body of a fully-developed male child, partly concealed in a hole formed by the stones of the wall, a few tufts of withered grass laid on the lower portion of the body. WJW went to Bryn Hermon to tell his elderly neighbours that he had noticed their servant KJ ‘about the place’ the previous day. RPJ accompanied him to the sheepfold, along with WJW’s wife and mother in law. He wrapped the baby’s body in a cloth and carried it back to his house. WRW then informed the police of his discovery and Kate Jones was subsequently examined by Dr. Evans of Caernarfon. The child’s body, unmarked except for a few slight scratches and discolouration about the head, was conveyed to the police station at Bontnewydd.[7]

At the inquest, held the following day, WJW elaborated on the statement he had given to the police. He told the Coroner he had seen his neighbour’s son, RPJ junior, walking with KJ away from the sheepfold and that she appeared to be trying to get away from him.

KJ had been found in bed by her mistress during the afternoon of the 15th September when she complained of her heart. Mrs JJ told the Coroner: “I suspected what was the matter with her but I did not tell her my suspicions. She told me she felt better and went out, did not say where she was going. Next thing I saw her she was coming on the arm of my son into the house”. KJ went into her room and RPJ junior told his mother that he understood she had fallen, he had found her with her face to the ground.

When he came home to find KJ missing, RPJ had gone out to look for her but then saw her coming towards the house on his son’s arm. She appeared to be weak and in want of support. He did not think she could have walked by herself. “She went into the chamber with my son. She went to bed. I don’t know who put her to bed unless my son lifted her up. No female went to see her unless my wife did”.

RPJ junior noticed KJ was not in the house when he returned from work in the quarry and thought she had gone out. Only after a few hours did he start looking for her in case she had had a fit. Walking towards the mountain he noticed a young foal looking over the wall of the sheepfold. He looked over the wall and saw Kate Jones lying on her side in a fit. “I went to her, took hold of her and on her recovering I spoke to her in about a quarter of an hour’s time. I asked if she had got better and she said yes a little better. I asked what was the matter and she said her heart was bad. I saw a little blood on her face. I did not see any blood on her hands. I did not notice any blood on the ground.” On the way back to the house, they passed a well and KJ stopped to wash her hands. “I took her into the chamber and she did not take off her clothes or boots. I stayed with her for about half an hour. My mother was with her when I left the chamber. My mother gave her some scottyn. I saw KJ more than once in the evening. She did not tell me how the birth took place nor who placed the body where it was found”. RPJ had no suspicion that KJ was in the family way when she came to work for his parents.

Dr. J. Evans, practising in Caernarfon, had made a post mortem examination of the newborn child. He found the navel cord was torn, 6 inches in length from the body, and no attempt had been made to tie it. The falling of the child might have caused the rupture of the cord or the child might have been born by the cord being pulled. The lungs were healthy giving no suggestion of suffocation and he concluded that the child had breathed but only for a short time. In his opinion death had resulted from loss of blood through the navel cord not having been tied which induced syncope and death. “I am confident that the child was born alive and had a separate existence from its mother, there are no marks of violence and I attribute death solely to the loss of blood”.

KJ had consented to a medical examination when it was found that she had recently been delivered of a child. She said that she had had a fit whilst in the sheep fold and could remember nothing of what happened. Dr. Evans found KJ in a “state of hysteria” when he saw her. He thought it most likely that she had a fit in the course of delivery and, assuming an epileptic fit, she might have moved to push away the body whilst in a semi-conscious state. A fit would also account for the cord not being tied.

The verdict of the inquest was that the child had been born alive but died soon after birth through the inability of the mother to render it assistance owing to her own condition of weakness. Excessive bleeding from the untied navel cord was the cause of death.[8]

MG may have been lucky to escape a murder charge for the babies in the attic. And while KJ’s plea that a fit had left her incapable of tying off her baby’s navel cord was accepted her case raises questions about her relationship with the son of the house.

Drowned, strangled or simply abandoned

The Coroner’s records show that other newborn infants were found left on the beach, in a field, at the roadside or wrapped in a parcel…and that a possible mother was never identified.

At Dwygyfylchi on 17th January 1898 a male child was found dead on the beach by a schoolboy Robert Jones. It had been washed by the tide and there were bruises on the body and fresh blood. The Coroner concluded the child had been born alive and that there was no evidence as to the cause of death.[9]

In a field adjoining the Conway Road in the parish of Eglwysrhos on 15th October 1900 the body of a female child was turned over by a plough. There was nothing found to indicate that the child had been buried as there was no hole dug. And no paper or clothing in which it could have been wrapped. Owing to the advanced state of decomposition it was impossible for the examining doctor to state whether it was a full term child or to state whether the child had ever had a separate existence.[10]

The much decomposed body of a newly born female baby was found in a pond near Waen Morfa Nevin on 4th June 1910. The remains were removed to St Mary’s Church Morfa Nevin where an inquest was held. The Coroner found the cause of death to be drowning but there was no evidence to prove how, when or by whom the child was placed in the water.[11]

A fully developed male child was found on the top of a wall surrounding one of the disused copper mine shafts on the Great Orme and an inquest held in Llandudno on 3rd April 1916. Dr H. Bold Williams could see no external marks of violence aside from bruises on the nose and mouth but he could feel there was a fracture of the skull through the skin and a post mortem examination indicated that there was some bleeding beneath the skull. Dr Williams said it was difficult to say how the fracture of the skull came about. It was not caused by a sharp instrument. It could have been caused, and probably was caused, by the child falling on the floor at birth. He thought the child had been dead from 24 to 48 hours but no longer. An examination of the lungs showed that the child had breathed but had not been properly attended to at birth and may not have had had a separate existence.

Witness Mr TS said that he and the landlord of the house in which he was billeted went for a walk on the Great Orme on Sunday morning. When they got as far as the shaft of an old copper mine they climbed up the protecting wall out of curiosity and they saw the body of the baby lying on top of the wall. They did not touch it but went away to inform the police.

There was no blood on the top of wall and his opinion was that the intention was to throw the body of the baby over the wall (which was 8ft to 12ft high). It would then have fallen down the shaft which was open and appeared to be very deep. At a distance it would be difficult to distinguish the body from a stone. The body had been placed on the wall very recently.

The jury returned a verdict that the child died through lack of attention at birth.[12]

A clerk was checking lost parcels at Bangor Railway Parcels Office on 24th August 1918 when he noticed a strong smell coming from an unaddressed parcel. In the parcel he found the body of a newly born baby boy wrapped in pieces of female underclothing.

Dr. E. O. Price found that child had breathed fully and completely after birth. Around the neck was a stocking firmly tied, the foot end of a stocking being forced into the mouth. The cause of death was strangulation and the Coroner returned a verdict of “wilful murder by some person or persons unknown”.[13]

The body of a newborn baby was found on the banks of a stream near Aber on 29th June 1925 wrapped up in brown paper. The paper had an address written on it but enquiries failed to provide any useful information. It proved impossible to say whether the child had had a separate existence and so the Coroner registered a verdict that there was no evidence as to how the body came to be where it was found and no evidence to show who the mother was.[14]

Found floating in the inner harbour at Pwllheli on 29th December 1915 was the body of a newborn female child. The body was spotted by two friends walking across the embankment bridge close to the sluice gates. They reported their discovery to the police and a local fisherman bought the baby, who appeared to have been in the water for some days, ashore in his landing net. A piece of lady’s black veil was tied tightly around the child’s throat.

Dr. Owen Wynne Griffith made a post mortem examination of the body and confirmed it had been in the water at least five days. The child was fully developed and the cause of death was strangulation.

Footnotes

[1] Lionel Rose, Massacre of the Innocents: Infanticide in Great Britain 1800-1939, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, Boston and Henley, 1986, p.35.

[2] Rose, 1986, p. 8

[3] Reports of the commissioners of enquiry into the state of education in Wales Part III, p.67

[4] 1881 census Carnarvon, Merioneth, Anglesey

[5] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald June 18th 1920

[6] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, June 25th 1920

[7]Gwynedd Record Office XCR/1900/106

[8] Gwynedd Record Office XCR/1900/111

[9] Gwynedd Record Office XCR/1898/4/5

[10] Gwynedd Record Office XCR/1900/116/11

[11] Gwynedd Record Office XCR/1910/20

[12] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald April 7th 1916

[13] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald 30th August 1918

[14] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald 29th June 1925