Even before the outbreak of World War I old certainties were being challenged. In North West Wales the number of men and women employed in agriculture was steadily falling and the slate industry upon which whole communities had depended was in irreversible decline. A succession of religious revivals culminating in the Great Revival of 1904 was followed by the emergence of a more secular society. And young women of the region could not have been unaware of the ground steadily being gained by various working women’s movements in cities across the border.

But these changes, only hinted at in earlier asylum notes, were accelerated by the war and the 1920 records from Denbigh more clearly reflect the profound economic and social changes experienced in North West Wales during the first quarter of the 20th century. They also evidence the move towards medical rather than moral treatments for insanity. Above all they are notable for the insight they provide into the suffering of soldiers and their families during and after the Great War.

‘These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished. Memory fingers in their hair of murders…’ Wilfred Owen ‘Mental Cases’ 1917

In April 1915 Thomas Williams, chairman of Denbigh Asylum’s Committee of Visitors reported that:

So far the War cannot be said to have had any remarkable influence on the number of admissions. The number of admissions in 1915 was 17 less than in 1914 and 4 less than in 1913….None of the male cases had been on active service. A marked increase in insanity is likely to take place after the War terminates.[1]

It soon became apparent that falling admissions into asylums was a national phenomenon and the following year Dr Frank Jones, who had taken over as Medical Superintendent in 1913, observed that the decrease would have been more marked had not the war itself been the actual cause of some cases of insanity.’[2] In fact the war played a part in 146 admissions from North West Wales between 1914 and 1924 and 90 of these admissions were from soldiers or sailors. But as predicted the numbers of ex-servicemen admitted to the asylum increased after the war and peaked in 1920. For a summary of all the admissions to the asylum during 1920 please see the Table below.

1920 Admissions: Current diagnoses

| Diagnoses | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Dementias | 3 | 1 |

| Organic disorders | 4 | 7 |

| Alcohol related disorder | 0 | 1 |

| Schizophrenia | 12 | 6 |

| Delusional disorder | 1 | 7 |

| Acute and transient psychosis | 3 | 4 |

| Unspecified psychosis | 3 | 1 |

| Manic episode | 1 | 1 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 5 | 3 |

| Depressive episode | 4 | 13 |

| Post partum disorder | – | 2 |

| Neurotic disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Personality disorder | 1 | – |

| Mental handicap | 2 | 3 |

| Epilepsy | 3 | 2 |

| General paralysis of the insane | 3 | 0 |

| Insufficient data (no case notes) | 1 | 1 |

| Not insane | 1 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 47 | 52 |

Young men from the quarry districts of North West Wales were likely to be conscripted to the Quarry Corps where their experience with explosives and tunnelling could be exploited and the impact of conscription on their communities must have devastating – in the same way that the practice of recruiting Pals battalions from young men from a particular region or trade left individual neighbourhoods without any young men when a battalion suffered heavy casualties.[3] With the introduction of conscription in January 1916, Pals battalions were no longer formed but the special expertise of quarrymen may have made it inevitable they would find themselves serving alongside others like themselves.[4]

HJ, a quarryman from Penmaenmawr, who served in France with the Royal Engineers Quarry Corps was admitted to Denbigh in 1918 from Murthly War Hospital in Perth with ‘the appearance of a man who has been insane for some considerable period’. HJ’s wife, whose voice he heard constantly telling him to ‘keep his heart up’, told Dr Jones her husband felt constantly pursued by soldiers and spent his time looking in the hedgerows around their home to see if any soldiers were hiding there. He also imagined his two brothers, one of them dead and the other still serving at the front, were in an upstairs room of his house. Classified as a ‘service patient’ HJ remained in the asylum tortured by his various delusions until 1931 when he was rushed to Denbigh Infirmary for surgery on a perforated gastric ulcer. The surgeon, Mr Duff, found the ulceration too extensive to repair and his patient died shortly after the operation.[5]

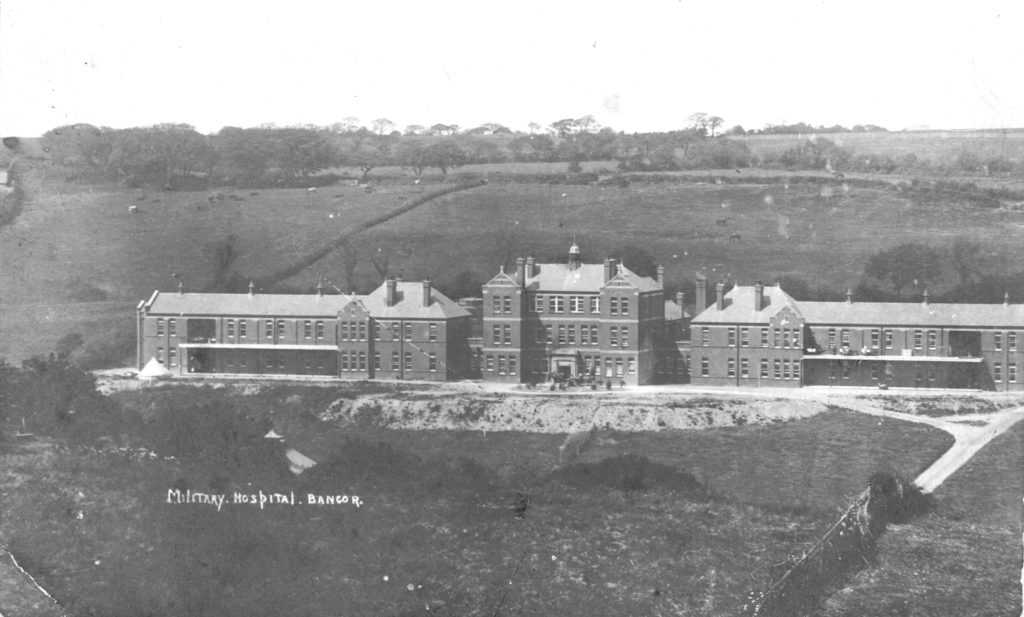

While HJ had initially been treated in Scotland most of the military patients admitted to Denbigh during the war were transferred from the military hospital in Bangor (pictured above). Built in 1913 to serve as a workhouse hospital to replace the old Bangor and Beaumaris Workhouse infirmary on Caernarfon Road, St David’s Hospital was just a year later commandeered by the Ministry of Pensions to serve as a military and rehabilitation hospital (for more on St David’s Hospital in general please visit Bangor Civic Society) [no longer available at http://www.bangorcivicsociety.org.uk/pages/hisso/v_stdavids.htm].

St David’s Hospital staff responsible for treating military patients 1917.

Most of the patients were soldiers who had lost limbs or were suffering from the effects of gas but others displayed behaviours which led to a diagnosis of insanity and were referred to the asylum for treatment.

Taken to the asylum in 1920 was EG from Llanfairfechan (9413) described as a ‘well-built young man with right eye missing – scar of old GSW over bridge of nose and right temple bone’ who was suffering from epilepsy as a result of his wound which was acknowledged to be severe and responsible for some injury to the brain. EG had been found in the lavatory attempting to kill himself with a razor and a leather strap.

Some of the soldiers at Bangor were accommodated in bell-tents sited in the gardens in front of the hospital. Amongst the treatments for cleaning wounds was Blue Stone – blue vitriol or hydrated copper sulphate – which was used to remove the infected skin and aid the formation of new skin. This treatment was later discontinued due to the poisonous effects of the copper sulphate![6]

Most of the ex-servicemen treated at Denbigh during and immediately after the war were classified as ‘service patients’ after admission which meant that their care was paid for by the state and that they were entitled to special privileges such as a weekly allowance – in 1920 this amounted to 2s 6d – and a special clothing allowance. The intention was to spare them the stigma of certification as pauper lunatics. WRL, a young farm labourer from Dolgelley (9449), described as a ‘very quiet and sad- looking individual’ who suffered from unshakeable delusions that he was being bayoneted, was one of these.

But it was up to the Ministry of Pensions to approve the classification and one of the grounds for turning down an application was if the patient had ever previously been diagnosed insane. Curiously though at least three of the servicemen accorded service class status were known to have had attacks of insanity before the start of the war.

RGD a 31 year old butcher living in Llanfairfechan had been treated in the asylum four times before his 1920 admission (9475) with recurrent mania. And HM’s diagnosis of melancholia on his transfer from the Lord Derby War Hospital in Warrington in 1918 was not his first. A private with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, he was suicidal when he arrived at Denbigh, believing that the authorities should have shot him in France, declaring that ‘his life is like hell on earth because he did wrong by trying to drown himself in France.’[7] The quarryman had been admitted to the asylum in 1912 for displaying similar suicidal thoughts.

Although there is no mention of an asylum admission, ETA’s reception order in 1919 refers to attacks 15 and 8 years earlier. A sapper with the Royal Engineers he had also been taken to the Warrington war hospital in the first instance before being transferred to Denbigh with melancholia ‘aggravated by active service’.[8]

PA from Colwyn Bay (9488) was not so fortunate. A letter from the Ministry of Pensions attached to his reception order in 1919 reads:

“With reference to Form I received in respect of the above named man you are informed that his present mental disability is considered by the Medical Branch of the Ministry to have no connection with his Military Service, and as the man was an inmate of an Asylum before enlistment, it is regretted that Authority cannot be given for A’s transfer to the Service Class”[9]

The 29 year old market gardener who had served as a gunner with the Royal Artillery was noted by the certifying doctor to have been treated at Cheadle Asylum for some months in 1914. He recovered quite quickly from his attack of mania and was discharged within three months but went on to have a further four admissions when he variously believed himself to be the Pope of Rome, the ‘cleverest man in the world’ and a friend of the Prince of Wales.

That HM and ETA were accorded service class status while PA was refused might be explained simply by their dates of admission. Very few soldiers were denied this special status during the war but the peacetime government was less willing to pay for the treatment of ex-servicemen, many of whom would clearly never recover from their sanity, so that by the mid-1920s 60 per cent were being refused.[10] PA may simply have been unlucky.

The man most likely to have made the decision to refuse PA service status was Dr William Whittington Herbert, who had retired in 1913 after 30 years as Medical Officer at Denbigh. After the war Dr Herbert was appointed neurological specialist to the Ministry of Pensions for the North Wales area.[11] Given Dr Herbert’s support for eugenics and advocacy of sterilization for the chronic mentally unfit[12] it is easy to imagine he would favour the policies increasingly adopted by the government and the military, along with significant elements of psychiatry, who ‘reasserted traditional classifications and diagnoses that peddled notions of ‘jerry-built brains collapsing under their own weight’, of class and gender stereotypes and or moral and social hierarchies’ in order to roll back pension awards to ex-servicemen.’[13]

Dr Herbert’s war effort also involved a year as medical officer in charge of POWs held at Queensferry and Lancaster internment camps. Wilhelm Helms, a fireman in the German army, was brought from Queensferry to Denbigh in 1915 fastened down on a stretcher owing to his violence. With the help of a German interpreter he blamed visual hallucinations for his noisy and violent behaviour at the camp but after admission remained quiet, well behaved and rational. The medical staff at the asylum found no evidence of insanity and he was returned to Queensferry a few weeks later.[14] In fact many of the camp residents were only technically POWs. German nationals living in Britain had been rounded up and arrested soon after the declaration of war as ‘alien enemies’ and since, without committing an offence, the police could not hold them as civilians, the War Office agreed to hold them as POWs. The Queensferry camp closed in May 1915.

The term ‘shell shock’ was first published in the Lancet in 1915 but the condition was poorly understood with some doctors believing it was the result of a physical damage to the brain, a cerebral lesion resulting from the shock waves of exploding shells, or from the carbon monoxide released from the shells and others considering it to be an ‘emotional condition’. The cost of shell shock in military and financial terms meant there was a strong push to avoid medicalising the condition and in 1917 the term was banned as a diagnosis by the British Army. Mentions of it were censored even in medical journals. This probably accounts for the fact that none of the ex-servicemen admitted to Denbigh were diagnosed with shell shock until after the war. TP from Llanrug was the first soldier recorded as suffering from shell shock and ‘slightly gassed’ when he was transferred from Whitchurch War Hospital to Denbigh in November 1918.[15] And shell shock is given as a cause of insanity in three 1920 admissions including in ST (9559) whose gunshot wounds to his hands and arms call to mind Wilfred Owen’s poem SIW: ‘ He’d seen men shoot their hands, on night patrol’. Although admitted in poor physical condition and the after effects of exposure and bronchitis, this young soldier would live in the asylum for another 57 years until his death from cancer at the age of 83.

ST shared with another long stay service patient, RW from Caernarfon, delusions that his drinking water was being poisoned. Ideas about being poisoned or drugged are not uncommon in the records but, during the war years, there were specific references to being poisoned by vaccination or inoculation.

Soldiers were inoculated against rabies, typhoid and smallpox before being sent to the front and at least 4 of the men admitted to Denbigh between 1915 and 1920 refer to after-effects. JK, admitted 1915 from Bangor Military Hospital stated on admission that he had ‘never been the same since he was inoculated against typhoid 2 months ago’[16] and ERJ, a young schoolmaster from Anglesey, complained of losing his memory ‘due to the fact that he was vaccinated secretly while in the Army’. [17] EOJ, who insisted that his illness was ‘due to being inoculated against typhoid and vaccinated against smallpox on the same day’ recovered so quickly that he was found to be not insane and discharged just 18 days after being examined. [18]

The asylum records paint a clear picture of the horrors endured by soldiers in the trenches. Slate quarryman and former solder DOT (9392) ran away from his home in Talysarn seeing ‘rats present in everything he looks at’ while JMJ’s firm belief that he was about to be shot for being a coward proved impossible to shake.[19] WO ‘suffering from some loss of memory’ denied he had ever served in France.[20] And the ‘unknown man’ (9554) found wandering in Aberffraw in 1920 and transferred to the service class on admission to Denbigh could not even remember who he was. The name ‘William Glynn’ is penciled into his case notes but it is impossible to say whether he recalled his name at some point or whether he was given the name by the staff who cared for him during the 42 years he spent in hospital.

To read more see: Linden, S. (2017) They Called It Shell Shock – Combat Stress in the First World War. Helion & Co Ltd.

Intimidated and teased

Among the patients granted service class status were some soldiers who had not seen active service, young men who had not been able to cope with the rigours of military training. EJJ was 19 when he was admitted to Denbigh from the military hospital at Kimnel Park Camp near Abergele after attempting to cut his throat. The only reason he could give for his suicide attempt was that he was ‘overworked in his training’.[21]

The asylum records suggest bullying was a significant problem at these training camps. EL was sent to the military hospital at Bangor when ‘teasing by fellow soldiers’ resulted in two suicide attempts[22] and JCO felt himself a victim of the Army authorities ‘constantly worried by their voices abusing him’. [23]

Built in 1914 as a training camp to prepare soldiers for service during the First World War, Kinmel Park Camp provided only the most basic accommodation but sold postcards like this one for soldiers to send home.

WJ, who was transferred to Denbigh from the military hospital at Oswestry Camp in 1917, hints at the difficulties young Welsh men in particular may have experienced during training. WJ could neither speak nor understand English and was described as anxious and depressed on admission. ‘But in a long interview conducted in his own language…his conversation was clear and rational’.[24]

A first hand description of one of these military camps was given by WJJ of Llanberis, who was treated at the asylum for six months after being found wandering in Denbigh in 1916.[25]

“The swearing there and the drinking was terrible…I was frightened. A very rough lot came up there. They even shouted at the officers. The wet canteen on the camp was closed for a week. All the public houses in the villages around were out of bounds. Coming into the hut every time of the night making terrible noise. I couldn’t sleep. I never slept but very little for about 11 weeks…”[26]

The letter was written from Bristol Prison where WJJ had been sent after absconding from a training camp outside the city in 1917 (to view the full letter click here). Before being called up, WJJ had been working at a Birmingham munitions factory where, with the experience of explosives he had gained at Dinorwic Slate Works, he had been appointed manager of the Hales-Grenade and Detonator departments.[27] Or as he put it: “I was the Explosive charge of two departments…”!

“I got quite mixed up in the Army. In the Factory I was doing well doing my best to my King and Country and helping my dear parents in there (sic) old days and keeping myself grand in health… Well Dr I am going to ask you will you kindly send on to me here a Certificate in connection with my health and an appeal to the Magistrates to help me to have a chance and get out of the Army to my own work of National Importance in the Factory…. They will be very pleased to have me back in the Factory. The case is next Monday”.[28]

It seems WJJ’s story had a happy ending. In August 1918 he wrote once again to Dr Frank Jones from The Shinglers Hotel, Wilson Street, Middlesborough:

“I never felt so well as I am today. I am in a very good position here. I am a Government Inspector at a Munition Factory, also I am married to the Proprietress of the above Hotel. She is 36 years of age and she was a widow and a very good one. Well Dr you have told me many a time that the best thing that I could do would be getting married. Well Dr I am going to ask a great favour from you. The Chief Constable of this town do want a Reference for me. My wife wants to have my name instead of hers. Well Dr you know that I had a bit of trouble and all due to Nerve Break-down. So I do hope that you will explain the circumstances clear to him. I have got a wife now to look after me and as you know I don’t touch drink. But I did abuse myself and there is no doubt it did affect the brain and I did few things against my own inclinations. But Dr I have married very wealthy. I am lucky and without a doubt I am looking forward to a very happy future and with your help there is a chance for me to come a prominent man in the town of Middlesborough. If you please will you kindly write the Chief Constable Middlesborough explaining all. I am in your good hands now and I will be allright waiting upon a reply from you… Your’s obedient servant, WJJ.

PS. Thanking you for your great kindness to me putting me in the Private Ward at Denbigh. We are staying with friends at Redcar for a few days. You can write if you please to us at the Hotel at Redcar.”

And he does not reappear in the Denbigh case notes.

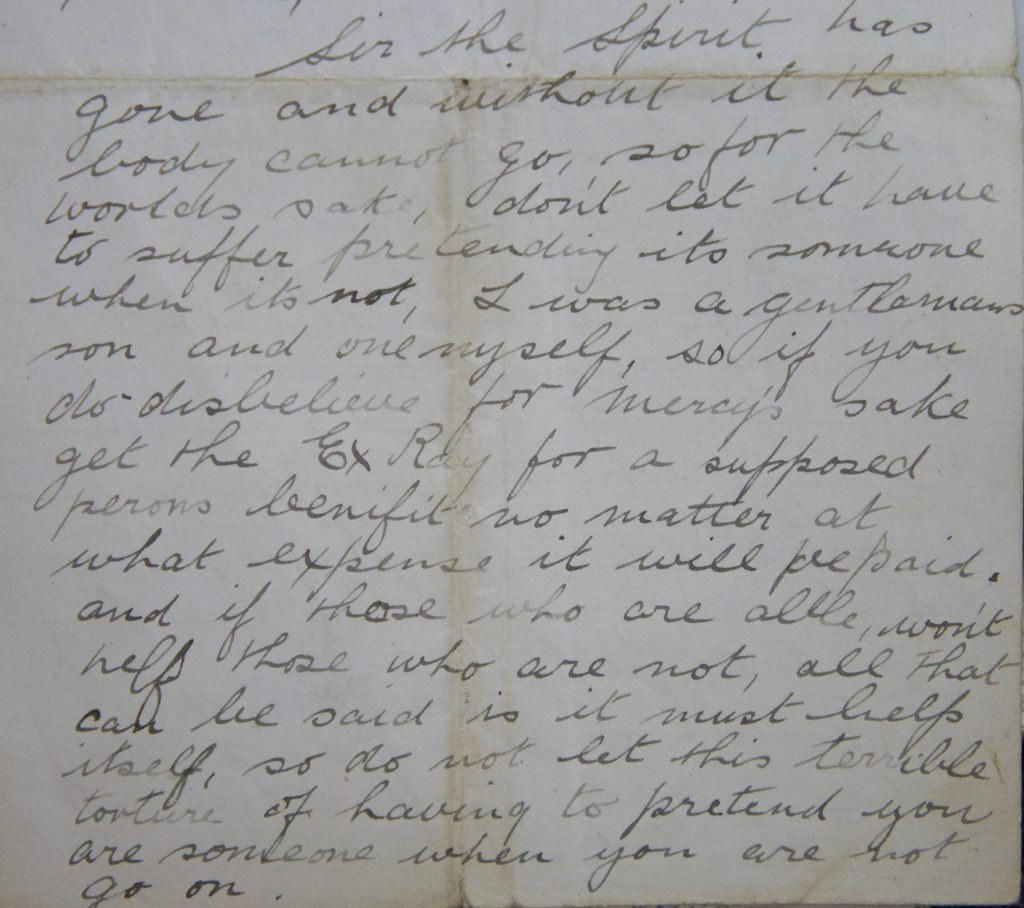

HTV from Arthog was just 17, his rank given as ‘Boy’, when he was admitted to Denbigh as a ‘Dangerous Lunatic Soldier’ in April 1918 and military training was cited as the cause of his catatonic condition. In two long letters, the first addressed to ‘The Medical Profession of all the World’, he referred to himself in the third person, as ‘IT’, and insisted that he was dead, that ‘nothing can bring him back to his body’. (see ‘HTV letters in casebook’).

The X-rays that HTV insisted would prove ‘this young life is over’ were finally arranged for him at Denbigh Infirmary in the hope they would dispel his delusions and met with limited success – he ‘promised to try and combat his delusion’.

However, after four months at the asylum his mother insisted on taking him home and, after she had signed a disclaimer below, HTV was discharged relieved.[29]

“I acknowledge that the above step is contrary to the advice of the Medical Superintendent and also that I have been informed that the chance of (him) being again received as a ‘Service Patient’ will be jeopardized and that in addition he may possibly lose a part of his pension.”

More recently HTV’s letters provided inspiration for North Wales composer Ellie Davies, for her latest work ‘Night Terrors‘.

Fear of conscription

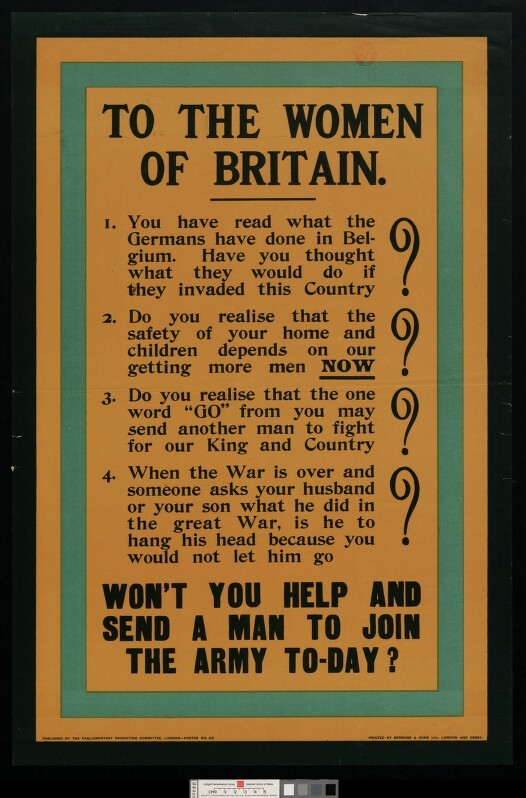

It would have been impossible for young men to ignore the many posters calling them to arms but after some initial enthusiasm for the war the number of men volunteering for military service sharply declined and in 1916 conscription was introduced. Under the National Registration Act any man between 18 and 41 would be called up and these conscripts made up the majority of serving British soldiers.

Fear of conscription was cited as a cause of insanity in several admissions from North West Wales. It seems that ER from Llangystennin feared the Army more than he feared remaining in Conway Workhouse because the medical officer at Denbigh entered ‘The National Registration Act’ as the suggested cause of his melancholia. With 8 months to go until his 42nd birthday it was not impossible that he would be sent to the front.[30]

Even though health requirements for conscription were progressively reduced, WT’s anxiety was probably unnecessary. His father, a Pwllheli farmer, told the certifying doctor in 1920 that his son had taken to his bed four years earlier ‘for fear of being conscripted to the Army’ (9485) but WT’s medical history suggests he may have suffered brain damage as the result of a childhood fall.

OR’s melancholia was attributed to an attack of influenza but it was also noted in 1919 that he had been ‘decidedly anxious about conscription during the last two years’.[31]

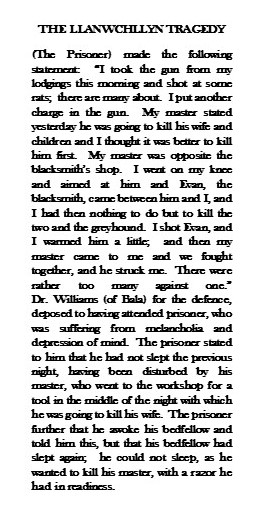

Proposals to introduce conscription in Ireland may have enhanced support for Sinn Fein. But it can be assumed that WTH, brought by ambulance to the asylum from the ‘Irish Prisoners’ Camp’ near Bala after a suicide attempt, was already firmly committed to the cause of independence by this time.

Frongoch was an internment camp for Irish rebels set up after the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and Michael Collins was interred there for a period during which he provided lessons in guerrilla tactics for his fellow prisoners so that the camp became known as the ‘University of Revolution’ or ‘Sinn Fein University’.[32] WTH was transferred to Grangegorman Asylum in Dublin by the Home Secretary in 1917 and died there shortly afterwards.[33]

The presence of Irish revolutionaries in the region may have accounted for the delusions of a woman who was brought to the asylum by her husband in 1920 talking incessantly and incoherently ‘about Sinn Feiners…and various other things’ (897).

‘When they have gone, we in a twilight place

Meet Terror, face to face…’

Evelyn Underhill ‘Non Combatants’ 1917[34]

Posters like this one acknowledged the power of women to influence husband and sons to volunteer. How effective they were can only be guessed but for women like AEJ and CJH, whose men had volunteered – with or without their encouragement – fears for their safety at the front were exacerbated by childbirth and both women were admitted during the early part of 1916 suffering from postnatal insanity. AEJ fell into severe depression, threatening to throw her baby on the fire, while CJH was convinced there were German and Jewish women in her bedroom and that her baby was dead.[35]

BP became insane shortly after her husband, a motor mechanic from Colwyn Bay, was conscripted. A neighbour who had looked after her for a few days reported that she was continually talking and crying about her husband and ‘eats none, will not have it and sleeps none’. Mr P’s employers, J Fred Francis and Sons, Coachbuilders, tried unsuccessfully to obtain his discharge from the Army and wrote to Dr Frank Jones in 1919 asking him to help:

“Now the Army people at P’s depot in France require more particulars to enable P to be demobilised on compassionate grounds. Providing you can see your way to please be good enough to say, either that his wife is fit to leave the Asylum if Price is home to look after her or, that if he was home it would mean that his wife would be more contented and perhaps it would be the means of improving her state of mind and be the means of her release. If he has this note from you, they tell him that it will only mean a few days before he can be demobilised.” [36]

However they had not given the patient’s name and Dr Jones pencilled a note at the top of the letter ‘I don’t feel inclined to give a certificate.’ It seems unlikely that BP’s condition would have improved had her husband been demobbed. He survived the war but his wife remained in hospital until 1946 when she died from heart disease.

MT, who had continued to farm at Blaenau Ffestiniog after her husband’s suicide, saw three of her sons conscripted. JT, a banker, was first hospitalized in France after attempting to drown himself at Le Havre and admitted twice to Denbigh Asylum suffering from melancholia.[37] Displaying the physical symptoms of general paralysis – ‘gait unsteady, reflexes exaggerated’, he was discharged after three months to the Neurological Hospital, Queen Square, London[38] (see Linden et al 2013 ‘Shell Shock at Queens Square’) but readmitted ‘raving mad and uncontrollable’ in 1922, again as a service patient, after trying to cut his throat.[39] His brother WT, who had helped his mother on the farm before the war, died after ten years being treated at the asylum for melancholia.[40] The admission of a third brother appears in J’s and W’s case notes but no record of this can be traced.

The loss of husbands, sons and brothers are all recorded in the Denbigh asylum case notes. EAR, a Blaenau Festiniog clergyman’s daughter, attempted to cut her throat when she learned her husband had been killed in action and continued to be suicidal in hospital – ‘said she was going to swallow her false teeth and was found with her handkerchief around her neck’.[41] EAR recovered from her melancholia and was never readmitted but the war ‘finished the battle’ for at least one other woman. MJH, who died in the Caernarfonshire and Anglesey Infirmary in 1916 from loss of blood resulting from self inflicted injuries, left this note:

“I have fought hard for over two years. I can’t sleep. The war has finished the battle. Dear and faithful William, dear Katie, Willie my brave son, little Emrys, remember to lead a good life…”

The family physician, Dr R J Helsby, who had been treating MJH at home for depression told the inquest that in his opinion ‘the worry of the war, her eldest son having been out at the front and wounded’ had aggravated symptoms first manifested two or three years earlier.[42]

Amongst the female ‘war casualties’ admitted to Denbigh was EMP, a nurse in training who may have worked at the front during the conflict. She and her brother HMP were admitted together having been taken into police custody after causing a disturbance at Evans Hotel, Llandudno. HMP, an architect and ex-serviceman, was discharged within six months to the care of a sister living in Abersoch, while for EMP it was a different story.[43]

Mrs E, her sister was keen to care for EMP at home and wrote angrily to Dr Jones in 1920:

“Do you think it businesslike or kind to keep my brother and Miss P (L, another sister) from Monday to Saturday without letting them know the Committee’s decision on their sister’s case? Were there any Drs on the Committee or only lay men? Will you kindly give me the list. I only asked that Miss EMP might come to me for a few weeks to see if a different treatment and surroundings would benefit her and, if not, then I would take her back to you. Dr Jones says she is no better mentally – physically she is much worse and has already lost 20 lbs in weight; also the Dr is of the opinion that a lady who has taken a Sister’s duties in one of the most advanced and important hospitals in the Kingdom and with the doctor living within five minutes walk from here are (sic) not as capable of taking charge of a mental case as one of his own nurses! If this is how the ones broken through serving their country are treated it is no wonder there is such terrible unrest. We thank you for your kind suggestion re the cost of maintenance but the point is that Mr and Miss P are determined to have their sister out and I am prepared to take her any time the Dr will allow her to come.”

EMP’s recovering brother also wrote to discuss EMP’s maintenance at the asylum – she had been transferred to the private class after admission – explaining that he found it increasing difficult to continue the monthly payments of £4 4s.

“We are ready to have her out and Mrs E has made it clear that she will take the responsibility for my sister – she was a sister-in-charge of one of the largest hospitals in the kingdom before she married. In addition there is if necessary a Doctor within 5 minutes walk. I myself have been examined by 2 nerve specialists since I have been away from Denbigh and they differ very much indeed from Dr Jones’ point of view. We think my sister’s physical condition when we last saw her was so changed as to be in the nature of a shock to me. Her letters to us are normal. Her conversations with me were normal. Will you therefore please put the matter before the Guardians. PS: Will you kindly let me know when we may take my sister away from Denbigh.”

EMP’s condition varied from ‘quiet and well conducted’ to ‘impulsive and threatening’ and in 1923 she was diagnosed with chronic mania, later with schizophrenia. HMP signed an agreement in 1924 to pay 3 guineas per week for the care of his sister but she was re-transferred to the pauper class ‘destitute’ in 1927 and, in 1951, the Acting Medical Superintendent recorded that nothing had been heard from the brother for very many years.

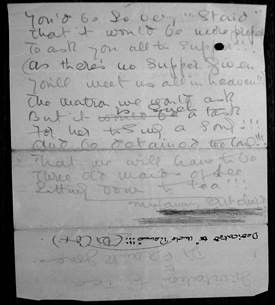

This rhyme written in pencil by EMP is pasted into the case book:

Three old maids of Lee

Tomorrow meet for tea

No men will be allowed

As we are rather proud!!!

And cannot be as swell

As some who’ll go to hell!???!

(Though L _perchance will be

A merry place you see!!!)

Had the kitchen been whitewashed

Three men we would have squashed

Into so small a space

That it would be a case!!!

Of standing up to tea

And sitting down to grace!

And making a great haste

There’d hardly be a taste

Of jelly and blanc-mange

And we’d be so afraid

You’d be so very “staid”

That it would be…..prefer

To ask you all to supper!!!

(As there’s no supper given

You’ll meet us all in heaven!!!

The matron we won’t ask

But it is such a task

For her to sing a song!!!

And be detained too long!!!

That we will have to be

Three old maids of Lee

Sitting down to tea!!!

EMP was to remain in care for more than 40 years in total until her death in 1962.

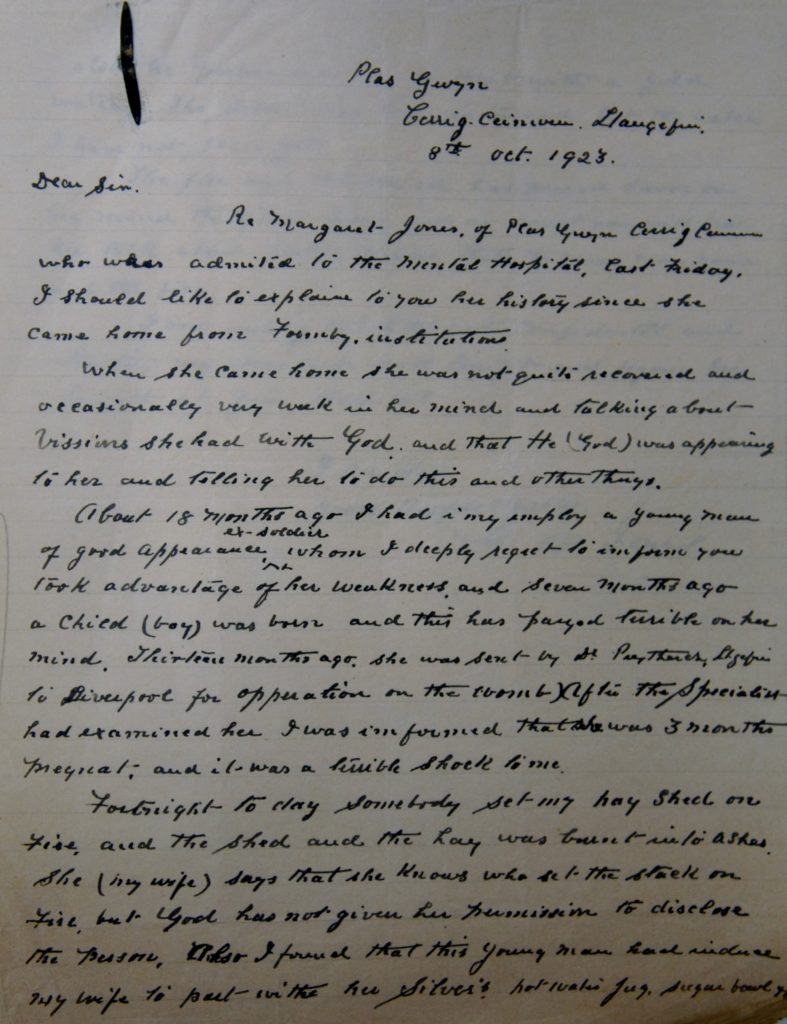

Other female victims of the Great War were European refugees who had lost their homes in the conflict and they are remembered in street names across North West Wales. Families in Caernarfon and Merioneth were sometimes called upon to take in war refugees like Mathilde A, whose neurotic condition – which caused her to attack her landlady in Towyn with a knife – was brought on by the loss of her home and capital in Belgium. [44] Mathilde had first become ill in Glasgow a year earlier where she was given the option of being removed to an asylum or leave the city. When the war was over Mr A wrote to Denbigh to request his wife’s discharge ‘as recommended by the Local Government for the purpose of repatriation to Belgium’ and she was accordingly discharged relieved to his care. Another reference to Belgian refugees is made in the case of GW from Barmouth who was reported by her daughter to be ‘maniacal at times towards the Belgians who stay in the house’.[45] The placing of these refugees with families in NW Wales gave rise to street names like Belgian Terrace in Caernarfon and the Belgian Promenade in Menai Bridge which was built by refugees grateful to the townspeople who had offered them somewhere to live until they were able to return home.

Keeping the home fires burning

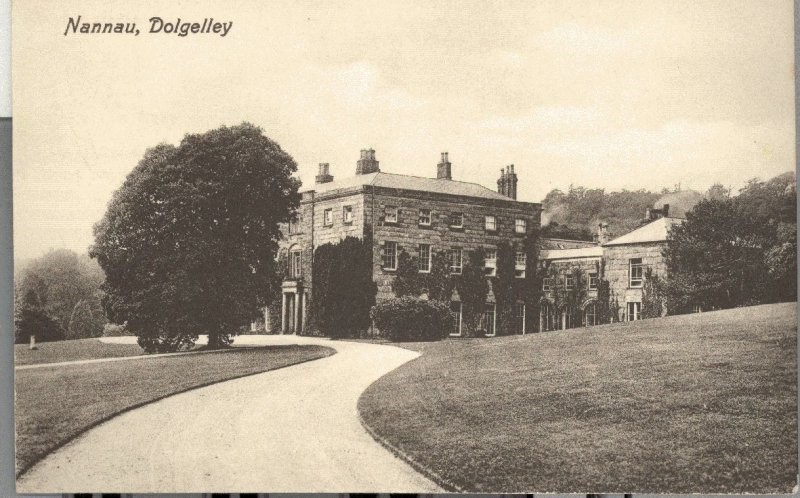

Nannau House, Dolgellau, was used as an officer’s neurological hospital during the war and local women volunteered, often on a part-time basis, to help nurse patients, cook and clean. In a letter home an RAF pilot who briefly stayed at Nannau in 1918 writes that:

“The sisters and nurses are very nice but are all ancient – you understand me better perhaps if I say ‘stricken with years’. The hospital is beautifully situated up in the hills and stands in its own grounds…for recreation there are plenty of nice walks and about two miles away there is a stream and a small lake where there is trout fishing. There is also shooting and I think that I will get more shots at rabbits before long.” [46]

Nursing was not the only contribution women in North Wales made to the war. Those ‘less stricken with years’ would have ‘filled in’ for the men at the front by working on railways and farms, policing their communities, delivering the post.

Ammunition factories were built along the North Wales coast with TNT produced in a factory at Penrhyndeudraeth and shells made at Portmadoc in workshops belonging to the Festiniog Railway Company.

The ‘munitionettes’ who worked in the ammunition factories were sometimes called ‘canaries’ because working with TNT caused their skin to yellow and their hair to fall out. But despite the risk of ill health and the danger of being severely injured or burned, morale in the factories remained generally high because for many women it was their first opportunity to work outside the home alongside other women. Like WJJ these women would have felt proud of the contribution they were making to the war effort and it permanently changed their expectations of work after the war had ended.

However, ABJ’s experience of work in a munitions factory did not last long. While travelling from her home in Towyn to Birmingham in March 1916 a box fell from a luggage rack onto her head and when she was brought back to North Wales just three weeks later suffering from mania her mother blamed this for her insanity – although it was not A’s first attack.[47]

Hopes that women had of continuing to earn their own living after the war proved in many cases unrealistic because those who had taken men’s jobs were forced to give them up for returning soldiers but even so there were more women in the workplace in 1920 than there had been in 1914. And although the outbreak of war had halted the long campaign for women’s suffrage in 1918, with a new view of what women were capable of doing, parliament granted women over 30 the right to vote.

Wartime asylum

If the war had relatively little effect on the number of admissions to Denbigh Asylum its impact on the operation of the institution was much greater. By 1916, 33 male staff were in active service including assistant medical officer Dr Benson Evans, 24 attendants, 7 craftsmen and a storekeeper. By the end of the war two of the nursing attendants, W Morris Williams and William Pritchard, had been killed in action and painter, TA Davies had also died in France. William Parry died later from pneumonia, his health having broken down during military service. Three attendants had been awarded Military Medals – W D Roberts, Robert Roberts and Edward Williams.

Staff shortages resulting from the loss of nursing attendants to military service were dealt with by appointing a number of men above military age or otherwise disqualified from serving in the forces as temporary attendants and by recalling several pensioners. Dr Jones also successfully appealed for the exemption of four attendants who were likely to be conscripted and a further four staff were temporarily exempted for three months. These measures provided a ‘generally satisfactory’ solution.

However, female nurses and attendants were being drawn to better paid ‘male’ jobs outside the asylum and 17 nurses left in 1915.

Recruiting suitable female staff remained a problem after the war and in 1920 Dr Jones reported ‘difficulty in obtaining candidates whose education would permit of them passing the necessary examinations in Mental Nursing’.[48] The same year, a group of (presumably well educated!) nurses posed for the photograph above.

Another ‘flu epidemic and the continuing battle with tuberculosis

Influenza outbreaks had been a regular occurrence at Denbigh Asylum and the ‘Russian Flu’ of 1890 had been responsible for a significant number of patient deaths. The 1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic, which resulted in the deaths of more than 50 million young previously healthy adults, attacked 88 patients and 36 members of the staff, including Dr Frank Jones, with six male patients dying as a direct result and others from respiratory complications. [49]

Another outbreak of influenza in 1920 affected 27 patients with fatal results to six of them. Although none of the affected patients were from North West Wales, influenza was identified as a cause of insanity in two admissions from the region during that year (9534 and 9446) and as the cause of earlier attacks in a further three patients admitted during the year.

The female sick ward 1920

However, it was not influenza which pre-occupied the Medical Superintendent in 1920. Tuberculosis continued to be the greatest risk to patients even though the wards were no longer overcrowded. The number of deaths had risen relentlessly since 1905, peaking at the end of the war, and in 1920 tuberculosis accounted for 29 deaths. The dairy cows on the asylum farm were tested for the disease and all the samples came back negative which ruled out the milk supply as a source of infection so that the blame fell on the asylum buildings and the wards and dormitories were accordingly sprayed with germicide. Wherever possible sick patients were nursed day and night in open air huts or on the verandahs and the Isolation Hospital was reopened to supplement this fresh-air therapy. The lunacy commissioners recommended that the weight of patients should be closely monitored and where any weight loss was identified that patient should be dosed with cod liver oil.

It was not only patients who were at risk of contracting tuberculosis. In his annual reports, Dr Jones referred to the deaths of at least two nurses after sanatorium treatment and in 1916 recorded the ‘serious illness’ of Dr Robert F Manifold, his Senior Assistant Medical Officer. In 1914 Dr Manifold had prepared four of the asylum nurses for Medico-Psychological examinations – ‘the first time that any Nurses from this Institution have entered’ – and all were awarded certificates. Even after his health began to break down, Dr Manifold remained responsible for preparing nurses and attendants for examinations but in 1920 he was admitted to Matlock Sanatorium and had to resign from his asylum post at the end of the year.[50] He died a few months later at a nursing home in West Kirby.

Dr Manifold was replaced by Dr Eustace Hutton, the Junior Assistant who had stood in for him during his long absence. Dr Hutton also took over Dr Manifold’s lectures on mental nursing with two staff passing the final Medico-Psychological examination in May 1920. A succession of locums were appointed to assist with his asylum duties – Dr Norman Thomas, Dr Ivor Lewis and Dr Sidney Davies – all of them Welsh speaking.

Diarrhoea and dysentery remained a problem with 49 cases occurring during 1920 despite the earlier construction of a disinfecting tank to sterilize all soiled and infected clothing and only ‘a short time after the thorough fumigation of all the wards’. Four patients from North West Wales died from dysentery, diarrhoea or colitis during the year.

A laboratory which would be useful in controlling epidemic diarrhoea as well as tuberculosis had become a pressing issue by 1920 largely because of growing concern about another disease which, could be diagnosed with the help of a blood test.

Tests and treatments for GPI herald ‘laboratory era’

Over the fifty year period – 1875-1924 – 164 patients from North West Wales were admitted to Denbigh suffering from general paralysis of the insane (GPI) and incidence of the disease reached a high point during the final decade of the 19th century. In 1895 it accounted for one fifth of male admissions from this largely rural region. In city asylums the rate of admissions was even higher with some reporting a third of male patients displaying the characteristic symptoms of GPI – loss of inhibitions, grandiose delusions, loss of memory, shambling gait and slurred speech.

The link between syphilis and GPI which had been suspected towards the end of the 19th century was generally recognised by 1905 and when the syphilitic spirochaete was identified in the brains of asylum patients diagnosed with the disease in 1913 there could no longer be any doubt. The Wassermann test had been introduced into Britain in 1908 as a means of managing syphilis but now it was adopted as a means of diagnosing GPI. The advent of the test promised greater scientific credibility for psychiatry and possibly stimulated the development of asylum laboratories although no pathologist was appointed at Denbigh until 1929 and the Wassermann blood tests had to be sent to Cardiff for analysis along with tests for dysentery and tuberculosis.

Until GPI was identified with syphilis it was often attributed to intemperance, ‘dissolute’ behaviour or heredity although the Denbigh notes suggest a link was being drawn as early as 1902. When ER was examined on admission in March of that year, although no cause for her insanity is recorded, she was ‘said to have contracted Syphilis from her husband, a seaman’.[51] The first case of GPI directly attributed to syphilis was an old soldier, JO, admitted in 1903[52] but there was still a reluctance to lift the blame entirely from the old culprits with JH’s insanity initially linked to his heavy drinking despite ‘old ulcer scars on both shins also old scars on the scrotum’[53] while responsibility for the GPI diagnosed in JR, ‘a great poacher’, was spread between the syphilis he had contracted 18 years earlier, intemperance and a strong family history of insanity.[54] With a tremulous tongue, shaky hands and marked knee reflexes MW looked ‘suspiciously like an incipient case of General Paralysis’ when he was admitted in 1906 but the diagnosis the stonemason was given – almost certainly on the basis that he had ‘lately been charged with bestiality and such offences’ – was Moral Insanity. In an apparently happy state he treated ‘all his disgraceful offences in a light jolly manner’ and he remained relatively content until a series of seizures confined him to bed and ultimately led to his death.[55]

The number of men admitted from North West Wales with GPI far exceeded the number of women. Of the 16 women diagnosed with the disease 12 were married or widowed and most of them were respectable housewives. EW’s medical history was provided by her quarryman husband who described her ‘chief symptom being a propensity for decorating her home etc with pictures etc’’![56] Among the symptoms of ER’s mania were that she had, perhaps understandably, taken a dislike to her husband from whom she had contracted syphilis four years earlier and that she ‘manifests now and again some most peculiar ideas chiefly matrimonial’.[57] A suggested cause for MW’s GPI symptoms in 1922 was ‘loss of husband in the War’ but, possibly out of respect for a dead serviceman or possibly because she was a private patient, syphilis is not mentioned in her case notes.[58] In contrast, when MAJ was brought from Caernarfon Workhouse in 1919 syphilis was given as the cause of her mania and it was noted that she had a ‘husband in Workhouse also infected’.[59]

A striking feature of the GPI admissions to Denbigh was the wide range of people affected. At one end of the spectrum were prostitutes and criminal hawkers and at the other engineers, clergymen and surgeons.

One of the two ‘clerks in holy orders’ diagnosed with GPI was JJJ, a 30 year old Oxford graduate, who was brought to the asylum from Caernarfon Gaol where he had been held on a charge of ‘Attempted Carnal Knowledge of a Child’.[60] He denied being on Bangor Mountain, where the offence had occurred, on the day in question and asserted that ‘he had never seen any of the children who had made a charge against him until he saw them in the Court’. Although he appeared to show no concern for his position the young clergyman’s case notes record that he had written to the representative of the Bishop of Pretoria in London and to the Secretary of the Immigration Society asking them to consider him for a living in Africa on the basis that he thought a change to a foreign country would do him good and the Medical Superintendent was careful to note that ‘he must have written to these people AFTER (sic) the charge had been brought against him’. JJJ did not think his prospects would be injured by the charge brought against him or by being declared insane declaring that ‘he had known other clergymen who became really insane and who recovered and returned to their church duties and did well’. He believed he would soon be back at his duties in Bangor.

However, within six months of his trial at Caernarfon Assizes, where he was ordered to be held at His Majesty’s pleasure and readmitted to Denbigh as a criminal lunatic, he was feeling sure that he had committed the offence although he insisted he had no recollection of being on Bangor Mountain on the day in question despite the fact that at this point his memory remained generally very good. Shortly afterwards a marked change in JJJ’s condition was noted: ‘His conversation is often very silly and his chief topic is about girls and most of it is disgusting and filthy…a young girl was very much frightened by something the patient said to her on the Asylum drive. His letters to his wife have been of a disgusting nature and have been stopped.’ By 1905 he had become helpless and increasingly feeble but survived another eight years. At no point in JJJ’s notes is syphilis mentioned and the cause of his insanity was recorded as overstudy.

Overwork was also thought to be the cause of surgeon WRH’s GPI which was initially diagnosed as melancholia although it was accompanied by difficulties with speech, loss of memory and ‘ideas of greatness – very proud of his jewellery and insisting on a clean shirt each day – constantly brushing’.[61] RHO, another surgeon, whose condition was put down to ‘an excess of stimulants’ believed his wife was trying to poison him, that people were sending out his bills without his consent and that he was pursued by ‘Moonlighters’ wanting to murder him. He was brought to Denbigh from Tuebrook Private Asylum, Liverpool, arriving late at night accompanied by the head attendant. He spent only a month at the asylum, dressed in strong clothing to prevent him stripping himself naked and sleeping on straw in the ‘refractory wards’ before becoming paralysed and dying from exhaustion after more than 100 seizures.[62]

Proportionally more GPI patients were treated privately at Denbigh Asylum. Amongst the businessmen and professionals admitted were a wine merchant, a shipbuilder, a chemist, a newspaper reporter and a district nurse. A photographer with an interest in astronomy and alchemy was admitted believing ‘all base metals to be pure gold’[63] and an artist deluded that he had made a fortune from his paintings. A Llandudno stage manager saw his bed at Conway Workhouse covered with monkeys and his daughter – who was touring on the stage at this time as Alma Zola – ‘larking at him outside the window’.[64] There were policemen, engineers, clerks, tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, stonemasons and insurance agents. However, sailors and soldiers formed the largest group of GPI patients with sunstroke often offered as a cause of their insanity as in the case of AHR who had been badly sunburned seven years before his admission to Denbigh while serving abroad in Burma, India and South Africa.[65] (see ‘Sunstroke & Insanity’).

Another sailor’s fears of having a venereal disease appear to have been unfounded. When TT was admitted in March 1920 the Medical Officer, examining the testicles which the patient insisted were being eaten away inwardly, recorded ‘I find nothing wrong with them’ (9394).

HJ, a young slate quarryman, was not so fortunate. He presented with clearly active disease and, suffering from a rash, sore throat and swollen glands, he was given a diagnosis of ‘syphilitic mania’ from which he is stated to have recovered within a year after treatment with mercury.[66]

Mercury in the form of an ointment, originally known as ‘Saracen’s ointment’, had been used to treat skin diseases since the time of the Crusades. Much later it was also administered orally, in HJ’s case as Mercury. Pil. Hydrarg., or as a liquor, a powder or a fumigation (see also ‘The Role of Mercury in the Treatment of Syphilis’). An arsenical compound Salvarsan was introduced in 1909 and also became a mainstay in the treatment of syphilis. Both continued to be used as treatments for syphilis until 1943 when penicillin was used for the first time.

However effective these poisonous ointments (see ‘A complexion to die for’) and pills seemed to be in treating the outward manifestations of syphilis they could not cure insanity but in 1917 an Austrian physician offered a new treatment for tertiary syphilis based on the observation that after a fever the symptoms of GPI appeared to diminish. After experimenting with pyrotherapy for around 20 years – first by attempting to transmit erysipelas to patients – without any satisfactory results, Julius Wagner-Jauregg infected a group of GPI patients with malaria and found that almost half of them achieved complete remission and were discharged able to work after 6 months from the start of treatment. The discovery represented a major breakthrough in the treatment of mental illness. Psychiatry had been brought into the laboratory era by the Wassermann test and malariotherapy offered the profession even greater scientific credibility.

Malariotherapy was introduced into Britain in 1922 by Dr R M Clark of Whittingham Asylum and proved so successful that in 1924 the Board of Control issued a circular letter to all institutions directing them to investigate the new remedy. A special mosquito centre was started at Horton Hospital in Epsom where a laboratory based in the 14-bed isolation unit at Horton became a national centre for mosquito breeding and sent infected mosquitoes to all British hospitals which used the treatment.

Patients with GPI were intentionally infected with malaria to create a fever. Three or four bouts of fever were enough to kill the temperature sensitive syphilis spirochaetes and these induced fevers were controlled by the use of quinine. The fevers could not always be accurately controlled and from 5% to 13% of patients died from malaria but so inevitable and so horrifying was the prospect of death from GPI – once into the final stage of the disease patients were bed bound, sometimes with their knees contracted up to their chin, and could do nothing for themselves – that the benefits were thought to outweigh the risk. Only after World War II, with the development of ethical parameters for research involving human beings, was the ‘do no harm’ principle given prevalence over the notion that ‘desperate maladies justify desperate remedies’.

A Llanrwst farmer who was transferred from a Yorkshire asylum in 1924 was one of the first Denbigh Asylum patients to receive malaria treatment. For this purpose he was boarded out to a specialized unit at Chester Asylum. It seems he never returned to Denbigh and there is no record of how he responded to the treatment[67] but it is possible he was discharged home after being inoculated. The case notes of three other GPI patients from North West Wales provide no real evidence of success for malariotherapy – they were all transferred back to the asylum after treatment at Chester and two died there. For the remaining patient no outcome is recorded. However, news on the efficacy of malariotherapy spread across the world with some experiments indicating that around a half of GPI patients showed some improvement after treatment and in 1927 Wagner-Jauregg won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his discovery, the first and only psychiatrist to be awarded the prize.

Malariotherapy came to be used in some hospitals to relieve other psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, manic-depressive psychosis, psychomotor cortical irritation syndromes, post-Parkinson’s encephalitis and psychoses of epilepsy and the area of research it had opened up continued into the 1950s. It was a far cry from the ‘poultices’, ‘champagne half hourly’ and ‘venesection of left forearm’ which had been prescribed for BJ who had been admitted to Denbigh in 1913 with symptoms of GPI[68]. Only in 1975 was its use in Britain finally abandoned.[69]

However unreliable the Wassermann test and however risky and unpredictable malaria treatment might have been, these developments were perceived as opening up possibilities for the scientific rather than the moral treatment of insanity and the asylum case notes from this period hint at a new confidence amongst the medical staff. It may not be entirely coincidental that descriptions of GPI symptoms around this period include a more ‘scientific’ terminology – references to Rombergism[70] rather than ‘unsteady gait’, Argyll-Robertson pupils[71] rather than ‘pupils unequal’ and to the Babinski sign[72] when testing reflexes.

The records for 1920 generally indicate a new spirit of experimentation. An ‘electrical apparatus’ was purchased in 1918 and five patients treated the following year by cerebral galvanism but with disappointing results.[73] Electricity had long been used to treat a variety of medical conditions and psychiatrists were keen to keep pace with the successes of their medical peers. In early experiments electrodes would be placed on the patient’s hands but by the end of the 19th century with the aim of more directly influencing the brain they were placed on the head. The results were generally disappointing so that interest in galvanism as a treatment for insanity declined and interest in electrical therapies was only reawakened by the introduction of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) which was first used at Denbigh in 1941.

Dr Jones also notes in 1920 that ‘an operation on the Brain for the relief of Epilepsy’ had been performed by Dr Thelwell Thomas at Denbigh Infirmary but reports that, although carried out successfully, the surgery had little effect on the patient’s mental condition.[74] The Medical Superintendent’s earlier experiments with vegetarian diets for patients with epilepsy, where he had noted a reduction in the number of seizures in most cases, had been rather more encouraging.

While chemotherapeutic treatments for insanity remained few at this point the 1920 case notes open a window onto some of the treatments which would be brought into use over the hospital lifetime of the patients admitted during that year. Apart from sedatives, night draughts and stimulants long stay patients would eventually be treated with drugs like Largactil, Reserpine, Disipal, Vallergan – a whole range of psychotropic medicines which could never have been imagined in 1920.

ORR, a farm labourer diagnosed with dementia on admission in 1920 (9439) was ordered ‘Special Treatment’ with Largactil in 1957 and appeared to show a definite improvement, remaining quieter and steadier. When after two months of the treatment his face became red and puffy he was switched to Notensil but, when he was noted to be ‘manic and talking loudly and incessantly’, the Largactil was resumed and he remained intermittently on the drug until 1974. He had been at the asylum for over 50 years by this time and, after visiting him there and ‘taking into consideration his age’, a niece wrote to enquire about any help the family might expect with burial expenses! There is no record of a reply.

MP’s daughter was also concerned with funeral costs. She wrote to the asylum in 1934 to ask for a letter confirming her mother’s incapacity so that she would be able to claim insurance money for her father’s funeral – ‘They won’t let me have the money unless I get a letter from you. I can’t pay myself as I haven’t any money’. A pencilled note indicates the necessary certificate was forwarded. MP, who had been admitted in 1920 with delusions about ‘some furniture at Mr Lloyd George’s house’ (9469) began ‘Special Treatment’ with Largactil in 1961 and although the dose had to be adjusted to reduce the drowsiness it caused, and phenobarbitone withheld for a period also, she appears to have remained on the drug until her death two years later.

A ‘Dangerous Lunatic Soldier’, so convinced that he was suffering from gonorrhoea that he kept his penis tied up in a brown paper bag, also seems to have been adversely affected by Largactil – just one day after starting the drug he ‘was noticed to be pale at tea time and pulses very slow’. He recovered almost immediately after the drug was discontinued and, although it was not blamed for his symptoms on this occasion, when the Largactil was restarted a year later he was once again taken ill.[75]

A former guardsman admitted in 1920 suffering from neurasthenia as a result of ‘war strain’ and much later diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia was treated with Largactil in 1960 and the side effects were dramatic. His face had become very swollen at a dose of 100mg tds and the treatment stopped. However, this earlier adverse reaction did not prevent another course of Largactil being prescribed 1965. After two weeks, the drug once again had to be discontinued but just three days later the patient was dead. The notes do not link JMH’s death to his medication but rather to myocardial degeneration with acute pulmonary oedema (9383). As part of a much earlier experiment to find a remedy for long-term conditions, this patient had been given a course of sulphur oil injections in 1932 but for some weeks afterwards ‘there was considerably increased restlessness and activity with constant singing and chanting prolonged far into the night’ and the treatment was not repeated.

In 1920 Dr Jones complained that the ‘apparatus for the continuous hot bath treatment’ was still not in place but this was in use during the 1930’s at Gwynfryn, one of the houses in the hospital grounds, to treat patients displaying agitated, excited behaviour or patients suffering from insomnia. This relatively benign treatment which might last several hours and sometimes overnight – with patients served meals in the tub – involved fresh hot water constantly being poured in and the old water being drained away.

Shocking developments

Improvement in a patient’s mental condition after a fever or physical crisis of some kind had long been noted (and probably underpinned malariotherapy) but JET’s 1920 case notes make specific reference to the link between an epileptic seizure and an improvement:

‘He has had since my last report, had a slight apoplectiform seizure and was unconscious for some minutes. This was followed by a marked improvement in his mental symptoms’.[76]

Subsequent research into the link between epilepsy and insanity resulted in the discovery of drugs to bring on artificial convulsions which it was thought might prove effective in treating schizophrenia. In 1937 Cardiazol Convulsion Therapy, a method of inducing seizures, was claimed to bring about remission in over 80 per cent of cases and was eagerly taken up by asylums across the UK. The following year, a young shipping office clerk from Amlwch Port admitted in a stuporose condition and diagnosed with hebephrenia (the first time such a diagnosis appears in the Denbigh records) improved so significantly after a course of cardiazol that he was discharged home recovered within a fortnight.[77]

A young voluntary patient from Llandudno whose intense interest in spiritualism was believed to be responsible for her ‘confusional insanity’ in 1937 was also given a course of cardiazol – after prolonged sleep therapy had failed to produce an improvement – and she recovered sufficiently within a month to be discharged. The following year 50 patients at Denbigh were treated with cardiazol with what seemed to be promising results – even patients who did not recover sufficiently to be discharged showed some improvement.

Another of the ‘shock treatments’ introduced during the 1930s was insulin coma therapy to treat schizophrenia. This pre-dated cardiazol convulsion therapy but was potentially so dangerous and demanded such a high level of nursing to monitor the patient’s condition and terminate the coma with a timely infusion of glucose that a specialist unit had to be provided and this was not established at Denbigh until 1939.

Insulin coma therapy was used throughout the 1940s, often in a ‘modified’ form where the dosage of insulin was adjusted to provide the expected beneficial effects without the patient being fully comatose. Although in the case of EMP, admitted in 1919, a ‘special treatment’ with modified insulin begun in October 1947 was discontinued a month later when she fell ‘into coma and collapsed state’.[78]

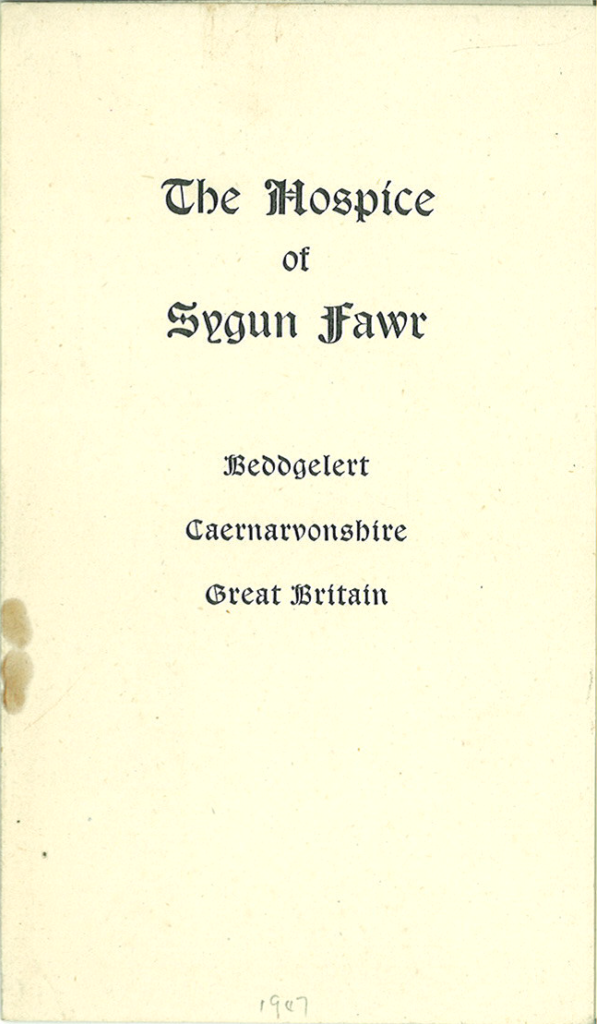

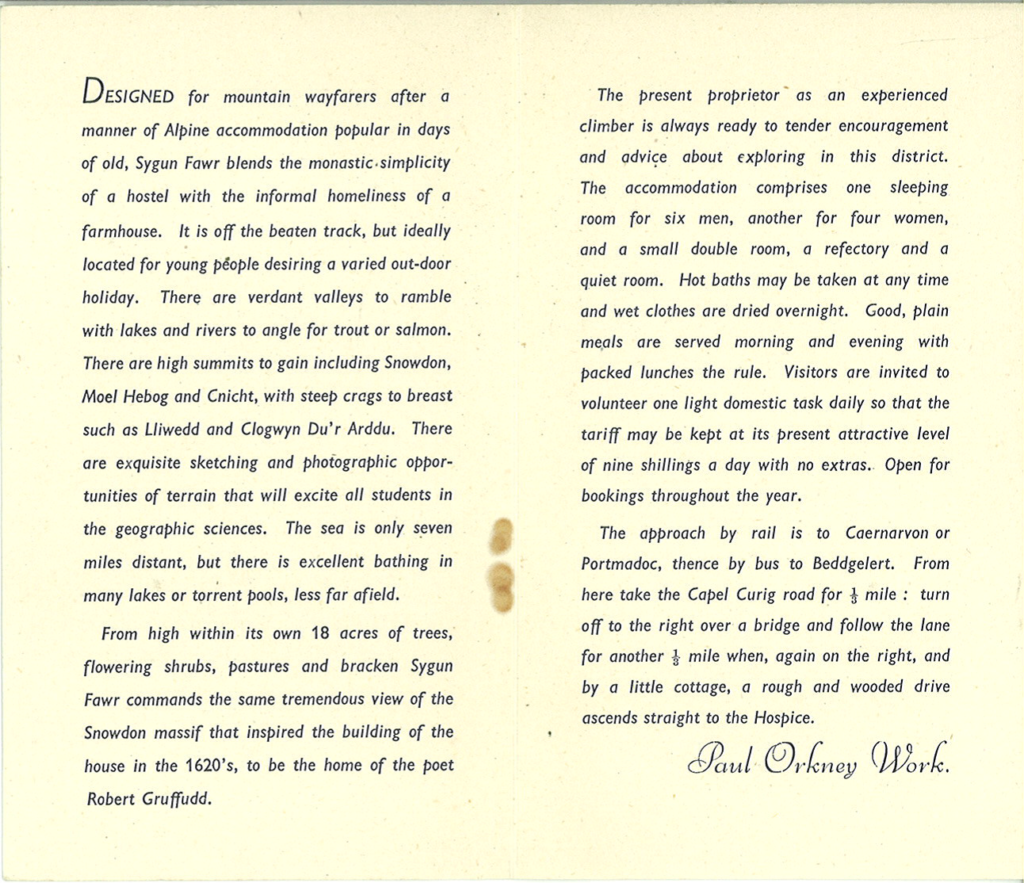

John Menlove Edwards, a psychiatrist and writer but perhaps best known as a pioneering rock climber, who spent four months at Gwynfryn after attempting suicide, described in a letter to his brother in 1950 a ‘rather vicious and long course of deep Insulin’[79] combined with electro-convulsive therapy. In his biography of the mountaineer Jim Perrin describes Menlove’s struggles to maintain sanity after being discharged from the asylum when he was taken by his cousin to Sygun Fawr Hospice near Beddgelert to convalesce in ‘the monastic simplicity of a hostel with the informal homeliness of a farmhouse’. The hospice was run at that time by another climber and author Paul Orkney Work whose co-authored book ‘A Walker’s Guide to Snowdon and the Beddgelert District’ had been published the year before.

Introduced at Denbigh in 1941, the first recorded use of ECT – the only convulsive therapy which remains in use today – on the 1875-1924 cohort of patients from North West Wales is encountered in the records of DW who was admitted in 1922 from Penrhyndeudraeth Workhouse at the age of 19. His early case notes are missing but he was given ‘electrical treatment’ in 1952. A letter from DW’s brother encloses a signed form consenting to the treatment to which the Medical Superintendent replied:

‘Thank you for your letter and the permission for treatment. His mental condition is very poor, we have asked for your agreement to give him electrical treatment, as when he gets very noisy and difficult to manage he wears himself out and tends to make his tendency to bronchitis worse.’

Early ECT patients were not anaesthetized as they would be today and the strength of the shock not tailored to individual requirements so that some sustained bone fractures as a result of the force of their fits.

In DW’s case the convulsive therapy appears to have been a last resort. But he had already been subjected to another ‘last resort’ treatment being one of the first patients at Denbigh to undergo psychosurgery. Correspondence with relatives, much of it in Welsh, points to the patient being noisy and difficult to manage and in 1944 permission was sought from relatives for a leucotomy:

‘Chances of a complete recovery are not good but it is hoped that his life may be made happier and more comfortable. There is a risk but this seems justifiable. Please let me know your opinion, and, if you wish to discuss the matter with the patient’s doctor, please write in order to make an appointment.’[80]

Leucotomy involved making a hole in the scalp and extracting a circular piece of bone. A wire loop would cut through the white matter at the centre of the brain’s two front lobes. In his annual report for 1943, the Medical Superintendent stressed that leucotomy was reserved for ‘hopeless cases – as a last resort after the demonstrated failure of all other forms of treatment’.

GJW visited his brother, catching the 8.38 train from Bryncir Station, and after discussions with medical staff, signed a consent form. DW’s operation was scheduled for 22nd September 1944 and he was one of the patients whose condition before and after surgery was recorded as a part of a research exercise to assess the effectiveness of the procedure. Described before his leucotomy as ‘restless, very destructive, faulty, homicidal, has completely lost contact with reality’ at a six-month follow up he was ‘rather inert, not aggressive, occasionally tears things, employed on simple tasks’.[81] However, a letter dated 1950 refers to DW as unoccupied and noisy and whether the subsequent course of ECT made any difference is not recorded. After 44 years at the asylum, this patient died from pneumonia in 1966 following surgery for a duodenal ulcer.

Around 300 patients were operated on at Denbigh before leucotomy – described in 1993 by David Crossley in his article, ‘The Introduction of Leucotomy: A British Case History’, as ‘something of a historical embarrassment’ – was discontinued in the early 1960s around the time that the photograph above was taken.

Learning Disability

Among the patients admitted during 1920 were five who had a learning disability even though the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913 had established a board of control to ensure local authorities made provision outside existing institutions for the care and management of people deemed to be ‘idiots’, ‘imbeciles’, ‘feeble minded persons’ or ‘moral imbeciles’. A report commissioned in 1908 had found that around 1 person in every 180 had a learning disability of some kind and recommended that these people should be cared for in special institutions or ‘colonies’ rather than in workhouse infirmaries or asylums.

Annual reports from Denbigh Asylum show that progress was slow:

‘The provision of accommodation for mental deficients within the counties in Union cannot be said to have made much progress since the last report and, as a consequence of the war, may be considered as relegated further into the background. In view of the fact that, as intimated by the Medical Superintendent, about 130 of the patients in the Asylum might be considered as coming within the terms of the Act.’[82]

After the war the Committee of Visitors reported no progress at all beyond a proposal to convene another conference to discuss a ‘joint scheme for the accommodation of Mental Deficients’ being agreed to by four of the North Wales county councils but not accepted by the remaining one.[83] Dr Jones’ was as concerned with the interests of the institution as with the wellbeing of his affected patients:

‘The removal of all Mental Deficients as well as the quiet and harmless chronic cases to ‘homes of a more simple character’ would enable certain wards at Denbigh to be set apart for acute cases and also allow for private class accommodation to be improved and thereby help the financial position of the Institution.’[84]

From reports in the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald in April 1921, it appears that at least one of these ‘homes’ was up and running by this time. A 15 year old boy had disappeared from the ‘home for Mental Deficients recently opened at Carnarvon’ and had not been seen since. Young WG – ‘height 5ft 4in, wears a blue Guernsey, brown corduroy knickers, black stockings and new heavy laced boots’ – suffered from epilepsy and was unable to speak coherently. Last seen alive passing through Betws Garmon, his body was found in Gader Lake a week later and it was presumed that he had been making for his parents’ home in Penygroes when he fell into the water.[85]

Among the patients admitted to Denbigh Asylum with a learning disability in 1920 was EW, a 14 year old girl from Llanerchymedd (9481) who was being cared for in Valley Workhouse before becoming ‘uncontrollable, dangerous to herself and others’. EW died in the asylum from general tuberculosis in 1926 but MEO, a domestic servant who had been certified under the Mental Deficiency Act in 1917 and had been a workhouse resident since the birth of an illegitimate child three years earlier, spent 50 years at Denbigh. Soon after her admissions she had a seizure and in 1924 her diagnosis was changed from congenital imbecility to imbecility with epilepsy. She was treated with Disipal and Reserpine (1958) and Largactil and Vallergan (1965), her name appearing on the drug sheets as ‘MEO (Rubbish)’ – presumably a nickname derived from her habit of picking up and storing any kind of rubbish (9383).

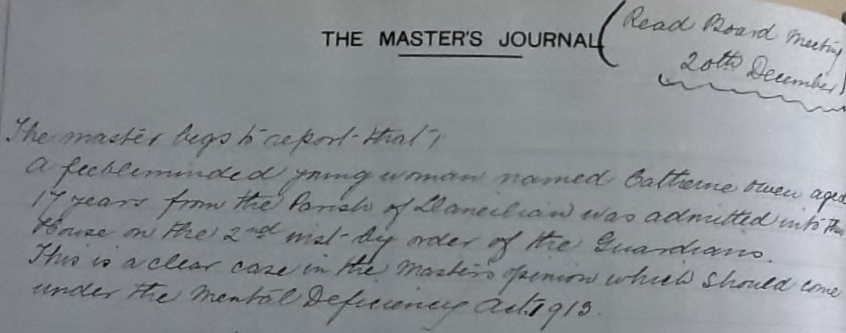

Cassie (Catherine) Owen was sent to Llanerchymedd Workhouse by her grandmother at the age of 17 after losing two of her ‘places’ in domestic service. Classed as ‘feeble minded’, Cassie spent the following 40 years as a workhouse inmate, first at Llanerchymedd and later at Valley, followed by 27 years in residential care and, when she was well into her eighties, an extraordinary oral history of her institutionalised life was recorded on 1st March 1984. (See ‘Cassie Owen Interview Summary’ for further details).[86]

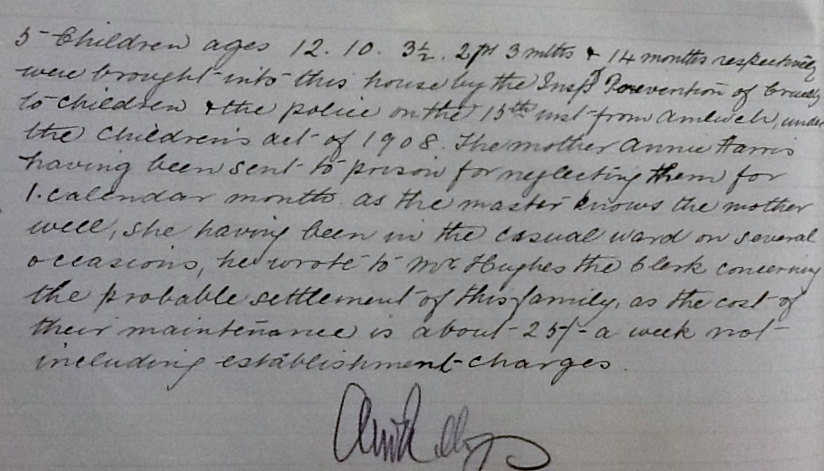

This entry in the Llanerchymedd Master’s Journal records Cassie’s admission to Llanerchymedd Workhouse

Cassie was happy at Llanerchymedd where she was well fed and kindly treated. The master and matron, Mr and Mrs Waterson, allowed the inmates to wear their own clothes and their birthdays were celebrated with cakes and jelly and trifle. Mr Waterson built a swing for the women – ‘He made the swing by the gate for us to have, to make us jolly, you know, not to be unhappy’ – and he brought a gramophone for them to listen to after supper. When Mrs Waterson died in 1918 Llanerchymedd Workhouse was closed and, with her fellow inmates, Cassie was moved to Valley Workhouse where she was never again referred to as ‘feeble minded’ and where she found herself subjected to a much stricter regime.

Cassie’s interview can be heard in full here:

Early interventions for ‘incipient insanity’

Dr Jones’ concerns about providing care for ‘mental deficients’ outside the asylum was matched by his enthusiasm ‘for the early and prompt treatment of mental cases, before certification and removal to Asylums’.[87] In this he echoed the earlier ideas of his predecessor Dr Stanley Hughes, who had been appointed Medical Superintendent at Denbigh in 1910. Dr Hughes’ progressive ideas about treating ‘incipient insanity’ included a network of outpatient clinics and a new reception hospital especially for these cases but, because he remained in post at Denbigh for just three years, his proposals were not implemented.

In 1919 Dr Jones attributed the high recovery rate in military mental hospitals to the fact that the former soldiers were not certified so did not feel stigmatized by their admission and that they did not come into contact with the chronic insane.[88] He thought mental wards should be provided within general hospitals for inpatient and outpatient care so that asylum admissions might be avoided and treatment delivered promptly, noting that almost 20 per cent of patients admitted in 1918 had been unwell for over a month prior to admission and nearly 50 per cent had been unwell for more than three months ‘such delay being always to the disadvantage of the patient’. He recommended three centres for North Wales – Bangor Infirmary, Wrexham Infirmary, and Denbigh Infirmary.”[89] However, annual reports after 1920 indicate that treatment for ‘incipient cases of insanity’ still remained a cause for concern.

Dora or David?

Dora L had been suffering from insomnia for six weeks before being certified in 1920 when the cause of her mania was suggested to be worry. One of the reasons for Dora’s ‘worry’ was undoubtedly her sexual identity because when examined on admission she was found to have few female characteristics (9425). Described as a ‘pseudo hermaphrodite’ the young domestic servant was, following correspondence with the Board of Control, re-classified as a male and made a full recovery within six months feeling ‘much relieved’ to be classed as a man. By the time he was readmitted in 1936, again with mania, David L had married and was running a farm. It was noted that his wife made no reference to any sexual difficulties.

Seclusion as a last resort

By 1920 diagnoses were becoming more varied although the term ‘schizophrenia’ which had been in use since 1908 does not appear in the Denbigh records until after 1930 with the earlier ‘dementia praecox’ diagnosis being applied to patients like DG (893) whose condition had been coming on gradually since adolescence and who was described as ‘a typical Dementia Praecox case’, ‘a perfect example of Flexibilitas Cerea’ and a ‘first rate example of Catalepsy’.

A young man admitted as ‘manic depressive’ the same year but retrospectively diagnosed with schizophrenia was a sailor boy from Holyhead (9513). During his manic episodes RWP would become violent and destructive and at one point ‘did his best to swallow his false teeth’ – which resulted in his being put on ‘the Card’ and deprived of the said teeth! Another attack led to a few days of seclusion.

The seclusion of a patient, and the hours of seclusion, had always to be carefully recorded. In 1889 for example the Commissioners in Lunacy reported that 20 of the male patients at Denbigh had been secluded during the past year for a total of 1289 hours (an average of 64.48 hours per patient) and 5 women secluded for 392 hours (an average of 78.4 hours per patient).[91]

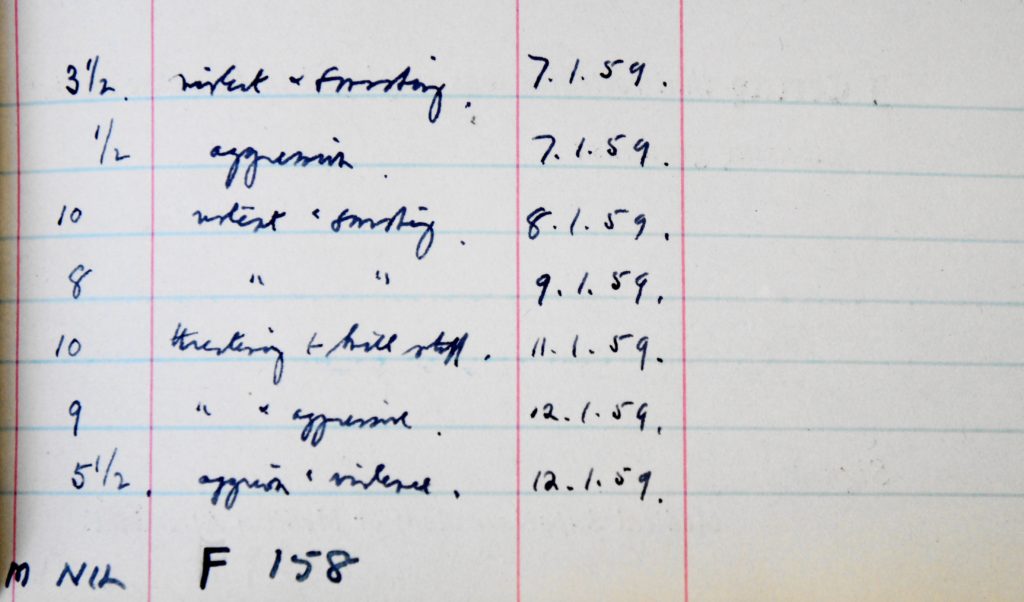

A ‘Register of Mechanical Restraint and Seclusion 1925-1960’ suggests that during this later period the majority of seclusions came to be imposed on women. MJH when ‘uncontrollable’ was secluded 14 times over a period of three months in 1929 for a total of 53 hours, the shortest period of seclusion being half an hour, the longest 7 and a half hours. Only two male patients were secluded during the same period with the longest single period of seclusion being 12 hours. And a ‘totting up’ of hours in January 1959 (above) showed no male patients had been isolated for destructive or aggressive behaviour during the previous three months.

Seclusion and restraint seem to have been measures of last resort and restraint was often imposed to protect patients from harming themselves. So in 1925 ED, who had gouged out an eye on a previous occasion, had special gloves put on both of his hands and tied at the wrists for 14 days in case he tried to do the same to the other eye. And MC was put in a long sleeve jacket for 8 hours after trying to tear off her left breast.[92]

In the 50 years from 1875 only eight patients from North West Wales are known to have committed suicide and just four killed themselves whilst in care which suggests that the measures taken to prevent suicide – seclusion, close observation, ‘caution cards’ etc – were largely effective despite periods of overcrowding and staff shortages. But in March 1920 MP, a hospital nurse from Bethesda who was thought sufficiently recovered from her melancholia to be considered for discharge, used the belt of her jersey to hang herself from a ventilator grid in the ceiling of her room.[90]

Bad stock…

Hereditary causes of insanity were reassessed after the war by which time it had become apparent that a poor family history, coming from ‘insane stock’, could not account for all cases of mental illness. The front-line experiences of ex-soldiers, the grief of women who had lost husbands or sons in the conflict and anxieties about work and relationships showed that trauma and social pressures were as likely to cause a breakdown in mental health.

However, fifty years of case notes from Denbigh reveal several families in NW Wales with more than one member seriously mentally ill. Amongst the patients admitted during 1920 was AW (9448), retrospectively diagnosed with bipolar disorder, some of whose descendants are today known to suffer from a similar condition.[93]

The daughter of an elderly station master Alice had first been admitted to Denbigh in 1892 at the age of 22 after an attack of influenza when it was noted that her older sister E had been an inmate of the asylum for six months in 1876 and that her mother M-A was also insane although being cared for at home.[94] M-A had been admitted to the asylum with acute melancholia in 1904 and discharged ‘relieved’ two years later after a trial of four months at home.[95]

The following year, the two sisters were readmitted within three months of each other, both from Penrhyndeudraeth Workhouse where they had been sent by their father who was presumably finding it difficult to cope at home with two insane daughters as well as a melancholic wife. Alice recovered from her subacute mania within a few months and returned to looking after the refreshment rooms at her father’s station until 1911 when, after exhibiting ‘irregular behaviour with men’, she was readmitted insisting that she had been returned to the asylum to look after her sister.[96] Unfortunately, however, E suffered a heart attack and died in the asylum in 1913.

By the time she was readmitted in 1920, from the police station at Barmouth, A was no longer her father’s problem. After remaining single well into her 40s she had married and it was her husband who reported her inclination to wander and that she had been ‘buying unnecessary things for household and was very extravagant and destructive’. There were three more admissions between 1923 and 1925 with maniacal attacks occurring ever more regularly and A died in the asylum from cellulitis in 1933.[97]

‘Liz Carnarvon’ was another mother whose two daughters became asylum patients.[98] EKD’s condition was described as the ‘ordinary acute mania of puberty’ but lasted well over a year while GD, who had ‘not been as others are since the age of 14’, was admitted twice, once in 1905 when the cause was thought to be the religious revival and the second in 1920 from which she did not recover (9566).[99]