‘An instructive and interesting lecture on Missionary Life and Experience in West Africa, accompanied by lime-light views*, was delivered by the Rev. Joseph Rhodes, and constituted an agreeable addition to our winter evening programme.’[1]

When the Rev. Joseph Rhodes, a Wesleyan minister living in Colwyn Bay, visited Denbigh Asylum during the winter of 1904 to deliver his lecture he would have found himself in familiar surroundings. He had been to the hospital two years earlier as a patient.

His admission to Denbigh as a patient in October 1902, aged 59, was not his first asylum admission. He had been treated at Stone Asylum in 1900 so that the cause of his current mania was supposed to be a previous attack. However, his case notes date the onset of his insanity to his return from the west coast of Africa where he had spent six years as a missionary and where he had contracted malaria.

Although admitted as a pauper, Rev. Rhodes was transferred to the private class the following day. He is described as ‘a very troublesome patient’:

‘He talks incessantly, rambling from one subject to another, first religion, then billiards, then hymns and so on. He is most restless and destructive and very inclined to quarrel with the other patients and use his fists. At night he generally sleeps badly and has to be put in a side room where he ties the blanket with hard knots and smashes the glass in the doors.’ [2]

His condition improved and deteriorated from week to week. Just a few days after the case notes record a little steady improvement, Rev. Rhodes struck three of his fellow patients:

‘Was playing chess today with…another patient who happened to disturb one of the pieces, when Rev. Rhodes slapped him in the face and, in return, got stuck on the head by the fist. There is a tiny wound on the right temple.’[3]

Rev. Rhodes was discharged on trial in April 1903, not recovered but ‘relieved’. The trial was successful and, when he returned to the asylum to give his lime-light lecture, he was quite well. He remained well for almost another year but in August 1905 began to suffer from insomnia, the precursor to another attack of mania, and was readmitted as a private patient the following month.

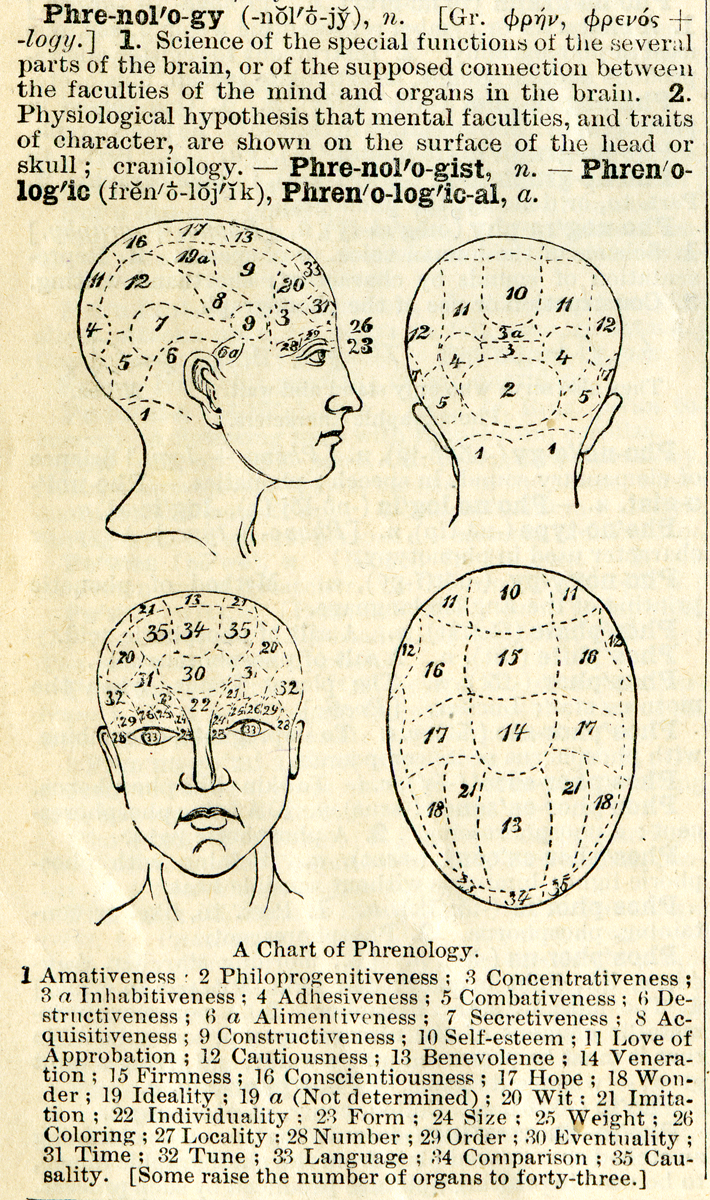

This time he was said to have removed articles from a pedlar’s basket, refusing either to replace them or pay for them. He had gone into a phrenologist’s room and pulled down pictures from the walls.[4] Perhaps surprisingly – he was after all a Methodist minister, this was 1905 and the religious revival was raging – his ‘preaching in the open air’ was also given as evidence of his insanity.

The case notes show that he was as troublesome during this admission as he had been in 1902 – restless, talkative and inclined to be violent and destructive – but very indignant about being detained. He was said to be smoking far too much and, in December 1905, it was noted that Rev. Rhodes was ‘much worse since his wife has been allowed to get him out daily’! He was discharged in February 1906, again ‘relieved’ rather than recovered.[5]

Rev. Rhodes had no further readmissions to Denbigh but his daughter FL was admitted to the asylum in 1931 as a certified patient. She had been deserted by her husband, Mr L, 15 years earlier and was living in poverty. These circumstances were given as the principle causes for her insanity but her father’s history of almost 30 years earlier was also noted in the case book and heredity given as an underlying cause.

FL’s condition is given as dementia and she spent ten years in the asylum, becoming increasingly uncommunicative and feeble, and died there from pneumonia in 1941.[6]

Footnotes

[1] 56th Annual Report 1904

*Lime-light or ‘calcium light’ was a type of stage lighting in widespread use in theatres by the 1870s. Created by directing an oxyhydrogen flame at a cylinder of quicklime, it was used to highlight solo performers. Rev. Rhodes may have used the light to show photographs of West Africa to his audience.

[2] DRO/HD1/372/151/adm no. 6079

[3] DRO/HD1/372/151/adm no. 6079

[4] Phrenology introduced the idea that character, thoughts and emotions were located in specific areas of the brain and that the capacity of these different areas could be inferred by an examination of the skull. Phrenological thinking was influential in 19th century psychiatry and also represented an important advance towards neuropsychology (Simpson, D. 2005. Prenology and the neurosciences: contributions of F.J. Gall and J.G. Spurzheim ANZ Journal of Surgery, Oxford, Vol.75.6; p.475). During the 19th century, some unscrupulous people abused the science for commercial purposes and ‘the Victorian period saw the emergence of phrenological parlours which were closer to astrology, chiromancy and the like than to real scientific characterology (Hoon, L. 1998 – www.phrenology.org).

[5] DRO/HD1/374/149/Adm no. 704

[6] DRO/HD1/359/Adm no. 11586