How it Began

The work that led to this website began in the early 1990s when the Department of History at Bangor University applied for a Wellcome Trust grant to investigate the history of the North Wales Asylum at Denbigh, sometimes called the Denbigh Asylum. The Wellcome Trust knocked the grant back. The world had too many asylum histories, it didn’t need another.

Merfyn Jones, then the Professor of History at Bangor, later Vice Chancellor of the University and Chair of Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, along with the lead researcher Pamela Michael recast the grant to cover the interaction between the asylum and social conditions in North Wales at the time. Why and when did the communities in North Wales use the Asylum?

They also tacked David Healy on as a medical element to the application. Healy had recently been appointed as a Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry based in North Wales.

The new application succeeded. It led to several papers by Pam Michael and to a wonderful book Care and Treatment of the Mentally Ill in North Wales 1800 – 2000, which brings out the politics of North Wales surrounding the building of the asylum, and the politics of healthcare in North Wales more generally that play similar roles now in 2017 as they did in 1847. The book gives a vivid picture of North Wales life and customs and the way mental illness presented in North Wales settings. This is traditional history well done. (The Table of Contents and Preface for this book has been provided by Cardiff University Press and can be found at the above link).

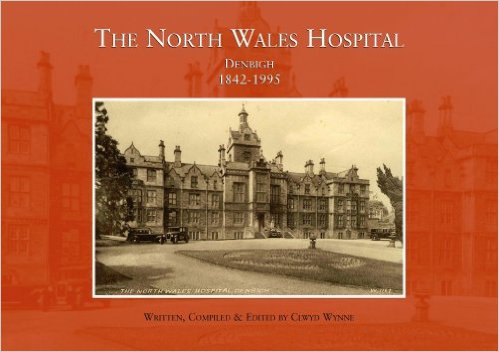

Even before this project had begun a lot of people within the North Wales Hospital were mobilising to preserve some record of the institution. The hospital was scheduled to close in 1995 and one of the senior nursing staff Clwyd Wynne had the brief to collect artefacts and photographs and testimony from both staff and patients about life in the hospital. This lead to the formation of the North Wales Hospital Historical Society and later their website [no longer available at http://northwaleshospital.btck.co.uk/]. It also lead to a book by Clwyd Wynne on the North Wales Hospital Denbigh 1842-1995, with the majority of the photographs featured on this website having been kindly donated by Clwyd.

Historical Epidemiology Emerges

The history embodied in Pam Michaels’ book illustrates the ways in which mental illness presented itself in North Wales 100 years ago. Compared with now it is striking how people for example declared their illness then by escaping from attention through the windows of their houses or by taking their clothes off. This doesn’t happen now. People then didn’t overdose or cut their wrists the way they do now.

Fascinating though this was and is, Healy and colleagues became interested in the quantitative opportunities thrown up by the North Wales Hospital records. Michael’s work involved entering 1 in 10 of all admission records to the asylum. Healy funded the project to enter all records of admissions from North West Wales for the years 1894, 1895 and 1896, with a view to comparing the profile of admissions to admissions to today’s replacement service, the then newly opened District General Hospital, Mental Health Unit, the Hergest Unit, in 1996.

North Wales was made by God for comparisons like this. It is the settling in which Tolkien based Lord of the Rings, with its mountains and castles. The maps of Middle Earth that appear in the Lord of the Rings show the same configuration as North West Wales.

- The region is bounded by the sea and mountains on all sides, so that 100 years ago and even now it is not easy to access mental health care from outside the area.

- The area was and is poor so that almost all healthcare access was and is through public facilities – there was very little private care.

- The area was rural then and remains so today.

- It was ethnically homogenous then with 80% of the surnames being traditional Welsh names and is ethnically homogenous now with over 60% still being traditional Welsh surnames.

This meant that with appropriate adjustments for population and control for shifting age bands, from a younger population 100 years ago to the population structure now, it becomes possible to compare the rates at which patients went into the North Wales Hospital 100 years ago and the rates that they enter the Hergest Unit now.

At this point – in September 1998 – Margaret Harris came into the frame. It was becoming clear that the differences between 1896 and 1996 were likely to be striking and that more work would be needed. Harris had majored in history in Bangor University as a mature student and answered an advert for a researcher on the project, a role she filled from 1998 to 2015.

- The first striking fact to emerge from the comparison of 1896 and 1996 was that there were far fewer admissions in 1896 compared with 1996. We had to bundle together 3 years’ worth of admissions to make it possible to compare what had been happening then with what happens now.

- The second was that the perception that mental health care takes place in small hotel like units now with patients staying for much shorter periods of time and that the care is more effective than before was wrong. We have an enduring image that patients then spent their whole life in the asylum along with over a thousand other inmates in hospitals that had been built to accommodate 100-200 patients at the most but had expanded to hold 1500-2000. This image began to seem wrong.

- The third was that the conditions people had were recognisably the same 100 years ago as they are now. Indeed faced with clinical records that contained not just the descriptions of the patient when they came into hospital 100 years ago but also a full record of all later admissions if there were any or the entire course of the patients admission in hospital if they stayed in hospital, it was easier to make diagnosis that several clinicians agreed upon than it is to get agreement on the diagnosis for patients today. Today’s patient on first presentation without the evidence of a clinical course can be far harder to diagnose.

The first article laying out these findings was published in 2001 (see Psychiatric Bed Utilization: 1896 and 1996 compared). To publish it, Harris, Healy and others needed to learn the language of epidemiology and the epidemiologists to whom they turned – Ezra Susser and colleagues in Columbia – had to learn some history.

It was now clear we needed to enter as many records from the past and the present as we could. The records from 1875 to 1924 provided a particular complete group. The Hergest Unit had opened up in 1993. We entered the key demographic and clinical details of all patients entering this Unit between 1994 and 2010.

The ability to make diagnoses and track the course of an illness but also the ability to have a system which gave us a good estimate of the actual number cases each year in a population which remained curiously constant over 100 years then threw up a real surprise – the appearance and disappearance of illnesses.

- The first intimation that illnesses might appear and disappear came with the evidence of the disappearance of classic post-partum psychosis. The usual response to this statement is that we still have post-partum psychoses – what are you talking about? There are experts on post-partum psychosis and the profile of this condition remains quite high but in fact the traditional illness has disappeared. Of the cases admitted 100 years ago, 80% were de novo onset in women who had no prior mental health histories and who had not further mental illness once the problem cleared up. It was an intense disorder, with features of delirium. This disorder rarely if ever happens today. The cases we have now are in fact first or further episodes of bipolar disorder that often antedate the post-partum episode which clinically look very different to the cases of post-partum psychoses 100 years ago. And while we were mapping admissions in the modern period, the mother and baby unit in the Hergest Unit, set up for post-partum psychoses closed down. There were no cases. Other mother and baby units across Britain also closed (see Tschinkel et al 2007: Post Partum Psychosis: two cohorts compared, 1875-1924 and 1994-2005).

- A second surprise came with our abilities to map the clinical course of Jerusalem syndrome or the schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorders that happen at times of social dislocation. The Welsh Revival in 1904 led to a spike in admissions to the asylum of people with acute and transient psychoses. We were able to track these patients later in life and see what happened. Did they come back into hospital or was the temporary insanity linked to the enthusiasm of the revival against a background of strikes in the North Wales quarries something that was a once off episode? The data made it clear that there were indeed schizophreniform psychoses that have a good outcome.

- The biggest beast in all psychiatry, lurking in these and other records, is the question of schizophrenia. The records made clear that for the first 20 years of the period we looked at, the incidence of admissions for schizophrenia was on the rise during the 1875 to 1924 period.

- But an equal surprise came in the 1994 to 2010 cohort where admissions began to fall after 2003. This rise in the 19th Century and contemporary fall offers scope to investigate what factors might have appeared during the 19th Century to help make certain psychoses chronic and whether those factors have shown a fall recently that coincides with the drop in the incidence of chronic psychoses. Two factors have been of particular interest to us. One has been the issue of lead contamination and the other has been changes in the nature of obstetrical care during the 19th Century and more recently (see The Incidence of Admissions for Schizophrenia).

At several points during this work over a 20 year period we applied to the Wellcome Trust to fund the work and found that they were reluctant to do so. The contemporary material wasn’t history we were told. When we looked for research funding from epidemiological or other contemporary sources, we heard the historical component was a problem – how can one be certain about events in the past like this.

We ended up creating historical epidemiology – something that hasn’t existed up till this and remains largely unrecognised.

Related to this is the fact that when diseases rise this is wonderful for business and everyone is interested but when they disappear as we found with the post-partum psychoses none of those who have an investment in the disorder are pleased. Our article and our data has fallen on deaf ears even though it has been accompanied by a closure of mother and baby unit across North Wales and elsewhere in the UK. The changes have been as visible as they were with the disappearance of tuberculosis.

In the same way one might have thought that evidence for an increase in the incidence and then a fall in the incidence of schizophrenia would be of wider interest but to date there has been very little interest in this possibility even though there are enormous service implications. Mental health services will need to be reconfigured in their entirety if what we’ve found holds true.

All of the above underpins the reasons for wanting to create this website.

To read more and find out how you can get involved see North Wales & You.