Attempts to tackle overcrowding at Denbigh Asylum by encouraging Poor Law Authorities to think twice about sending sick and harmless patients to the asylum rather than the workhouse hardly touched the problem. Although only the most urgent cases were being admitted by 1878, numbers continued to rise with beds pushed into any available space and sometimes so close together that patients had to get in and out at the foot of the bed. Dr Williams had to deal with regular criticism from the Commissioners in Lunacy about overcrowding and staff shortages but his major concern was for the patients in his care. In his annual report, he predicted that the hospital might become a ‘receptacle for the care and custody of the incurable’ rather than a place that patients might come to be cured and returned home.[1]

Even after the completion in 1881 of long overdue extensions it was clear that accommodation for patients remained insufficient. But this would not be a problem for Dr Williams who, after a visit from his nieces Hermina Eleanor (13) and Elizabeth Maude (11) in the spring of that year, left his post at Denbigh.

Dr Llewellyn Cox, who came to Denbigh from the Wiltshire County Asylum, inherited an ever more crowded and understaffed institution and from the outset had to field increasingly strong criticism from the Commissioners. But whatever arguments were taking place behind the scenes and however pressed asylum staff were to cope with their charges, increasingly using seclusion and restraint, the public image of Denbigh Asylum seemed to remain intact. In fact the asylum had become something of a tourist attraction and in 1881 visitors were impressed by the sight of ‘the lunatics walking beautifully in the grounds’.[2]

Dr William Whittington Herbert from Glamorgan, who had previously been employed as a ship’s doctor, was appointed to assist Dr Cox in 1883. The doctors would certainly have appreciated the degree of continuity provided by Mr John Robinson, who had been clerk and steward of the asylum since its opening in 1848, so his death in 1888 must have been a bitter blow in difficult times.

However, William Barker was to prove a worthy successor to Mr Robinson. When he arrived in 1889 from Lancaster Asylum it must have been immediately apparent to him that the situation at Denbigh Asylum was critical. The number of attendants was much below proper strength, sometimes not even sufficient for patient safety, let alone proper treatment as regards employment and exercise. The lunacy commissioners found in one male ward 43 of the most excited and turbulent patients, only 2 of whom were fit for work, supervised by just 4 attendants. Three nurses were in charge on a female ward with 46 very troublesome female patients.[3]

Officers and male staff 1884. Dr Llewelyn Cox, medical superintendent, is seated at the centre of the picture with Dr William Whittington Herbert, assistant medical officer, to his right and Mr John Robinson, clerk and steward, to his left. Denbighshire Record Office.

Officers and female staff 1884. Dr Cox stands at the centre next to matron, Miss Pugh, with Dr Herbert and Mr Robinson lying on the croquet lawn at the front of the picture. Sitting next to Dr Cox is Mrs Hannah Jones, head nurse. Denbighshire Record Office.

The steady increase in patients could largely be accounted for by the build up of chronic incurable cases and, although the number of new admissions was also rising, the house committee were at pains to deny any significant increase in lunacy. A table produced to illustrate their conclusion shows how the demand for asylum treatment had increased over a period of 25 years and how many patients continued to be looked after in the community.

No. of Pauper Lunatics over a 25 year period

| Date | Pauper Lunatics in Asylum | Pauper Lunatics not in Asylum | Total | Population last census | Proportion of insane to population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1864 | 260 | 516 | 776 | 360,831 | 1 in 464 |

| 1870 | 323 | 508 | 831 | 359,834 | 1 in 433 |

| 1876 | 374 | 480 | 854 | 394,921 | 1 in 462 |

| 1882 | 459 | 489 | 948 | 414,258 | 1 in 436 |

| 1888 | 554 | 497 | 1051 | 414,256 | 1 in 394 |

The committee offered the same reasons for the increase in numbers that Dr Williams had put forward in 1875, that strong feelings against sending a relative to the asylum continued to diminish, but added: ‘It must also be remembered that the average life of a lunatic in a well-managed Asylum is likely to be much prolonged beyond that of those who are maintained at home…where proper attention cannot be given to the mental and bodily wants of the afflicted’. [4]

They also noted the disparity between the five counties. The districts nearest to the asylum produced the greatest number of patients while North West Wales consistently remained ‘under quota’ and this bolstered an argument for providing increased accommodation for Flint and Denbigh by building a branch asylum for patients from Anglesey, Carnarvonshire and Merioneth in North West Wales. The alternative would be to extend the existing asylum at an estimated cost of £25,000.

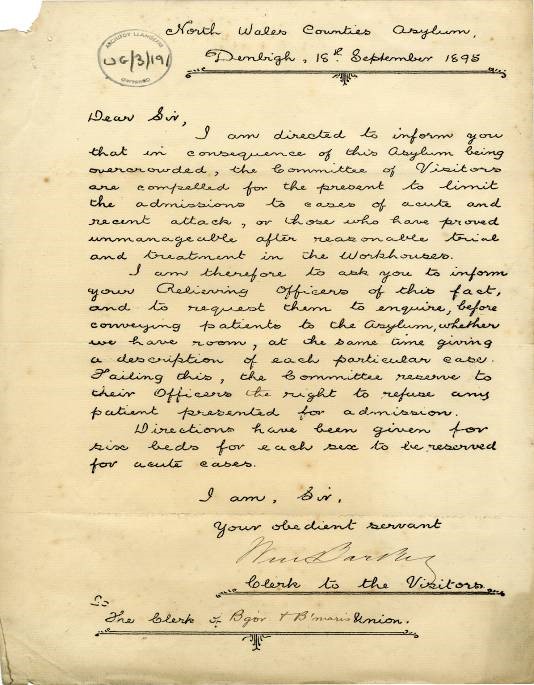

The house committee’s report marked the beginning of a lengthy and often vindictive dispute over which of these two options should be adopted with the committee of visitors favouring an extension and the lunacy commissioners preferring to build a new asylum in Carnarvon. The commissioners had observed that it was not possible to bring a patient from some places within a day and that patients from ‘distant parts’ would be rarely visited by family or friends. It would be another five years before the Secretary of State finally ruled in favour of enlarging the asylum at Denbigh. By which time it had become necessary to limit admissions to acute cases or to patients who had proved unmanageable in the workhouse. Relieving Officers were advised that six beds for each sex would be reserved for this purpose and that any other patients might be turned away.

Letter to Bangor and Beaumaris Union [5]

At the beginning of January 1890 there were 530 patients in the asylum – compared with 394 in January 1875 – and again only 10 per cent of them were expected to recover. A further 25 female paupers had been boarded out to Abergavenny Asylum at a cost of £300 per year to the North Wales counties.

The report of the lunacy commissioners on the previous year was fairly damning. They predictably expressed concerns about staff shortages but also drew attention to an increase in mortality from ‘causes of death which are not common in asylums’ such as dysentery, suffocation by food getting into air passages and the death of a violent patient caused by attempts to restrain him.

Arrangements for the supervision of suicidal patients were once again criticised. A negligent attendant had been reprimanded and had his wages reduced after the suicide of a severely depressed male patient and an unclimbable railing and locked gate ordered to be built around the pool in which the patient had drowned. Dr Cox was advised to issue special ‘caution cards’ to be kept by the attendants in charge, directing that suicidal patients be kept constantly in view, and that these cards should accompany the patients when they were moved from ward to ward, with counterfoils signed by each attendant to show his knowledge and responsibility. The cards should be withdrawn only when the doctors were satisfied that such strict supervision could safely be relaxed.

Twenty men had been secluded for a total of 1,289 hours and five women for 392 hours, the averages (64 and 78 respectively) suggesting that the women patients were more troublesome than the men. As indeed the commissioners had found in 1875.

One of the few positive notes in their report was that the Case Books were well kept. But by the following year the commissioners found these unsatisfactory too.

“Of course the case books are not as fully noted up as we are accustomed to see them, but they are better kept than we would expect with an overworked staff”.[6]

Russian ‘Flu

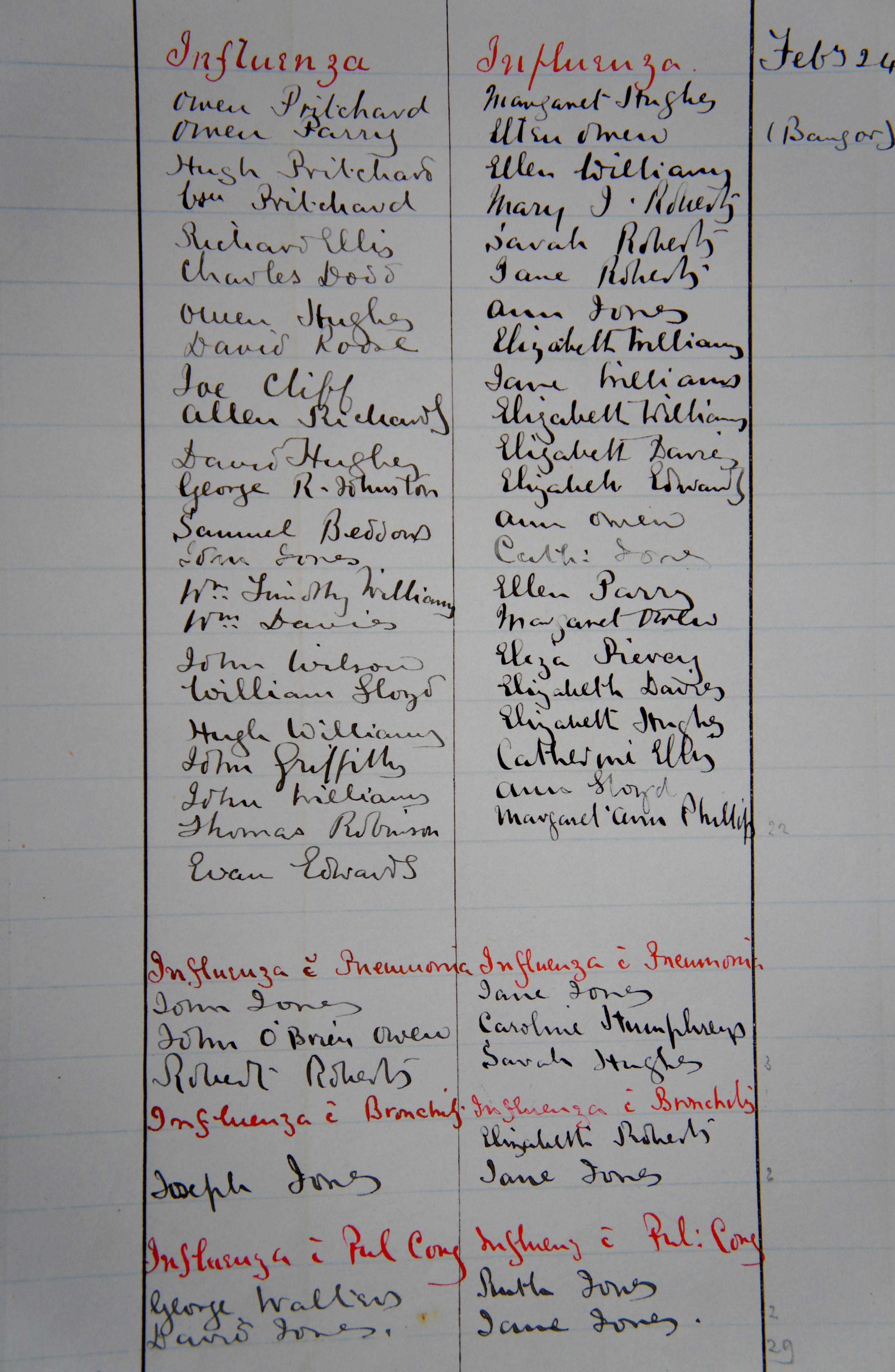

For the first three months of 1890 staff were particularly hard pressed. No sooner had a severe outbreak of pneumonia ‘of an extremely intractable character’ been contained than the asylum was invaded by an influenza epidemic then sweeping across most of Europe. Brought into the asylum by one of the female patients the Russian ‘Flu rapidly spread amongst patients and staff eventually attacking 131 patients and 26 attendants, proving fatal in a number of cases. Robert Williams, who had worked as a laundry attendant at the asylum for 27 years, died at his home after contracting the illness.

During the months of February, March and part of April, our dormitories adjoining the Hospital wards of each division were crowded with sick, the daily average number under treatment ranging from 25 to 30 males and 35 to 40 females, when the disease was at its height…. Towards the end of April many of the invalids were slowly recovering from the extreme nervous and physical prostration which followed the fever.[7]

Of course the staff had not only suffered from the same ‘nervous and physical prostration’ but also from the demands put upon them attending the sick while also taking care of the insane. For their efforts during the crisis they were rewarded by being granted a few days’ extra holiday.

The North Wales newspapers were saturated with alarmist stories about the ‘Russian Plague’. In January the North Wales Chronicle described the furnaces at Pere Lachaise being well employed with the cremation of the epidemic’s many Parisian victims.

However, it seems the press was keen to bring the panic a little nearer home and on January 25th an article headlined ‘INFLUENZA AT THE ASYLUM’ referred to rumours that patients were victims of the ‘dreaded disease’ and that at one time seven corpses lay awaiting burial in the house. The reported response from the asylum was that patients had indeed died – but from natural causes – and that the number was by no means out of the ordinary ratio in so large a population insisting that:

There has not been a single case of influenza within the walls of the asylum and the rumour was without the slightest foundation.[8]

Perhaps a somewhat disingenuous response, given that a pneumonia epidemic was raging on the male side throughout January, but the Russian ‘Flu seems to have arrived in the asylum rather later than it spread in the surrounding communities. Cases of influenza are entered into the Medical Journal in red ink with the first confirmed case written up on 12th February. This was John Jones of Llanrwst (4068) who died less than two weeks later by which time the names of patients being treated for influenza, with or without complications, covered an entire page of the journal.

The asylum’s handling of the press in relation to the epidemic is interesting. Newspaper readers clearly took an interest, sometimes a morbid interest, in events at the asylum and the institution was keen to be shown in the best possible light. The management would not be happy for rumours of unburied corpses to continue to circulate.

They would not have wanted stories of overcrowding to be made public either and in the same edition of the Chronicle another headline ‘NORTH WALES ASYLUM: IMPORTANT SUBJECTS DISCUSSED’ introduces a paragraph reporting that representatives of the press were asked to retire while discussions regarding additional accommodation took place and discreetly announcing that “…there is no diminution in the demand for accommodation of the Asylum”.

Even after the epidemics had abated, asylum staff were still clearly overstretched. In April a patient claimed that he had been kicked by an attendant resulting in broken ribs. His story was believed and the attendant in question, who denied any ill-treatment, was summarily dismissed. The lunacy commissioners regretted that a fellow attendant, who had backed up his lie, was left unpunished. They also regretted that the ‘Suicide Caution Cards’ they had recommended the previous year were not yet being used.

The commissioners’ observation that the 1890 case books were not as fully noted as usual seems borne out by entries relating to treatments. Whereas 72% of patients admitted in 1875 had their treatments noted, only 27% of those admitted in 1890 had recorded interventions. Chloral hydrate – a drug which had been administered to more than half of the patients admitted in 1875 – appears just once in the 1890 records. However, whether these scantier notes regarding medication can be blamed entirely on overwork during the influenza epidemic is questionable. Treatment entries had diminished over the previous 15 years at a more or less steady rate. And it is unlikely this was because fewer treatments were being administered.

In fact, although daily dispensary costs amounted to just £0.03/8, new drugs were appearing in the notes. Pepsin was found to ease vomiting in one female patient, a mixture of ipecacuanha and opium – later marketed as Dover’s Powder – was given to treat influenza, atropine used to treat an eye injury, chlorodyne to relieve bronchitis. Arsenic was administered in 1883 to a patient suffering from chorea and thought to make a significant improvement with ‘her speech being more distinct and the choreic movements not being so violent’. Another patient, whose insanity was put down to intemperance, ‘made considerable progress under the use of Iron and Strych(nine)’. In fact poisons like arsenic, strychnine, belladonna, hemlock and even cyanide were commonly used medicinally in the late 19th/early 20th centuries as draughts, liniments, tinctures, ointments and tonics. (For more information see ‘Poisons as Treatments’ a document produced by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in 2006, also available directly from their online collection).

Cannabis indica was employed as a sedative in the case of a ‘very respectable village postmaster’ suffering from general paralysis of the insane. However, from the same case notes, is seems that as well as these medications the place of exercise in the therapeutic regime is reinforced. The patient was:

Exercised all day long. The advantages of the latter are very marked. Instead of boxing a patient in a dark room as used to be done where his appetite failed and his irritation and restlessness are increased. We thus restrain the outward muscular movements while the motor energy is still being generated in the brain, a most unphysiological thing to do. Our great aim should be how to find suitable outlets for this morbid motor excitement instead of penning it in the system to give rise to Structural Cerebral Change with Dementia or Chronic Mania. We can best do this I think by letting the patient dance sing and shout as much as he likes and if possible put him to hard work of some sort. [9]

Such apparent disdain for restraint and seclusion did not prevent its use becoming more frequent and references to the padded room, the long sleeved jacket, the straight waistcoat, the closed sleeves and the locked gloves are scattered throughout the case notes. Although it should be noted that restraint was used outside the hospital too. For example, Mary Ellis was found to be ‘so wild that it was necessary to confine her in a straight jacket’ at least a week before her admission to Denbigh.[10]

In addition, despite more medications becoming available patients were bled and blistered well into the 1890s. A young quarryman suffering from mania who was noted as ‘always attempting to commit unnatural offences on his fellow patients’ had his penis blistered to ‘excellent effect’.[11]

A technological breakthrough!

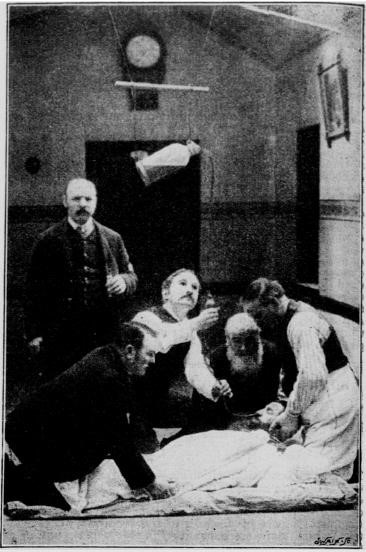

The treatment for patients who refused food was force feeding ‘by nose’ of milk or beef tea with wine or brandy and any prescribed medication. During the 1890s Dr Herbert would refine this procedure, using an old sweet jar suspended from a hook in the ceiling to dispense the liquid through a rubber tube inserted into the patient’s nose, and publish his improved technique in the British Medical Journal in 1894.

(Photo reproduced by kind permission of the Wellcome Library, London)

‘Fed by pump’ leaves little to the imagination and, not surprisingly, many patients did not require a second treatment. Perhaps out of respect for her age and feeble physical condition it was thought more appropriate to feed Ellen Jones from Penmachno ‘forcibly with fluids from the Teapot’![12] An alternative method of dealing with patients who refused food and medication was the enema and the Denbigh notes refer to feeding per rectum of beef tea and brandy and the administration of chloral, quinine and opiate enemata. It appears rectal nutrition remained popular into the 20th century with ‘long but scientifically unconvincing papers’ extolling its perceived benefits.[13]

Reports and case notes leave an impression that the asylum may have felt generally more regimented and rather less benign by 1890. There were several escapes during that year and one woman was missing for almost four days. On a stormy November night she had slipped through a door inadvertently left unlocked and avoided discovery by hiding during the day and seeking food and shelter at nightfall. Dr Cox reported that, with the exception of being tired and footsore, the woman did not suffer any serious physical harm and that she had been ‘treated with much kindness by the country people she approached’.[14] Nevertheless it was thought important to prevent further escapes by introducing a revised system of counting and recording patients before and after they assembled for mealtimes. Attendants were also provided with waist belts and chains to secure their keys which would surely have made them appear to their patients more like prison warders than carers.

Old friends

Jeremiah Owen who had been brought to the asylum manacled in 1875 remained a patient in 1890 and by this time was extremely unwell with symptoms of the tuberculosis which would eventually cause his death five years later. Throughout 1890 he suffered extreme pain from diseased bones in his foot and lower leg and Dr Cox, using an ether anaesthetic[15], was eventually forced to amputate the leg, optimistically observing some time later: “An excellent stump and will carry an artificial leg well and painlessly”.[16] But it seems Jeremiah never did get his artificial leg because in June 1891 he was said to be getting about easily on crutches and a prosthesis is never mentioned again. Only one other patient from North West Wales remained in the asylum from 1875 to 1890. William Owen, a wandering lunatic admitted from Llanerchymedd Workhouse after striking the matron there, remained at Denbigh until his death in 1910.[17]

Two other 1875 patients had readmissions in 1890. The Llysfaen laundress Anne Hughes had been admitted nine times since 1875 and by 1890 she was presenting with melancholia rather than mania (4160), her expression ‘that of a dazed person, with her hair hanging down, and which she is constantly pulling at’. Her son had needed to take time from work to look after her for fear that she would harm herself.

John Jones, quite literally a ‘lunatic’ (his father had attributed his first attack to the full moon), was admitted for a fifth time in 1890 (4194). He was working in South Wales as a labourer when he became unwell again and Richard Jones had to travel south to bring his son home. It appears John was quite content to be back at Denbigh, happily greeting his former acquaintances and ‘expressing a great desire to stay here to assist with the harvesting’. His case notes indicate his condition was extremely variable, at one time low at other times excited, and he remained in hospital for more than 10 years never remaining well long enough to be discharged. By 1902 when he was considered ready to leave the asylum he was spending much of his time in bed with imaginary complaints. He went from Denbigh to the workhouse at Penrhyndeudraeth, not cured but ‘relieved’, and no more is heard of him.

Despite attempts over the intervening years to persuade Relieving Officers to send to the asylum only those lunatics impossible to manage in the workhouse 62 patients were admitted from North West Wales in 1890 – 6 more than in 1875. This may not signify an unwillingness on the part of the Poor Law authorities to comply with requests from the asylum because the figures show that it was admissions for serious mental illness which increased – admissions for schizophrenia, acute psychoses and bipolar disorder – while there were fewer admissions for dementias and organic disorders. 61% of the 1890 patients had a serious mental illness compared with 32% in 1875 (see Table below – ‘1890 Asylum Admissions’). Taking bipolar disorder out of the mix, a significant increase in admissions for schizophrenia and related psychoses remains apparent and these figures from North West Wales support theories of an ‘epidemic’ of these conditions during the 19th century.[18]

1890 Asylum Admission: Current diagnoses

| Diagnosis | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Dementias | 3 | 1 |

| Organic Disorders | 2 | 1 |

| Alcohol related disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Schizophrenia | 12 | 8 |

| Delusional disorder | 1 | 1 |

| Acute and transient psychosis | 3 | 2 |

| Manic episode | 1 | 0 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 3 | 6 |

| Depressive episode | 4 | 2 |

| Post partum disorder | 0 | 3 |

| Neurotic disorder | 1 | 1 |

| Personality disorder | 1 | 1 |

| Mental handicap | 1 | 1 |

| Epilepsy | 2 | 0 |

| General paralysis of the insane | 0 | 1 |

| Insufficient data (no case notes) | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 34 | 28 |

Recent studies have shown a decline in the incidence of schizophrenia after 2005 and this raises questions about the possible causes of such a rise and fall (see Healy et al, 2012). Could it have been an increasing exposure to lead during the 19th century and a reduced exposure from the mid-1970s? Perhaps changes in obstetric practices? Anaesthesia had made way for clumsy and sometimes brutal measures in the 19th century whereas after the mid-1970s problematic births were managed by caesarean section. Or maybe it was the smallpox vaccinations made mandatory for infants in 1853 and discontinued when the disease was declared eradicated in 1980. Changes in ambient lead, developments in obstetric medicine and the vaccination programme all closely follow a schizophrenia ‘timeline’.

The asylum doctors were keen to find a cause for the insanity of the patients they admitted and, although Dr Cox reported that heredity and previous attacks remained the prevailing factors, old age, bereavement, money worries and ‘irregular habits of life’ also accounted for a fair proportion of admissions. And five female disorders were identified as causes of madness – puberty, childbirth, lactation, uterine and ovarian disorders and menopause. Miriam Williams had been admitted a few years earlier with mania characterised by ‘hypersthenia of the sexual organs: a thing not uncommon at her time of life’. Miriam, aged 47, had been visiting the houses of clergymen in Llandudno and ‘solicited intercourse with them’ her behaviour otherwise being quite rational. Her case was thought by Dr Herbert to provide a good example of symptoms dependent upon ‘ovarian or internal derangement’.[19]

A table included in the 1890 annual report not only assigns causes for that year’s admissions but also relates causes of insanity to outcomes (see ‘Causes of Insanity 1890’).

Perhaps not surprisingly, patients whose insanity was attributed to old age, epilepsy or a ‘congenital defect’ were likely to die in care. This was also true for intemperate patients and for patients whose insanity was not attributable to any particular cause. But an episode assigned to a bout of ill health might expect a more positive outcome and patients suffering from general anxiety and ‘worry’ would usually recover.

FOR BETTER…?

‘Love affairs (including seduction)’ was defined as a moral cause for insanity. ‘Love disappointment’ was not exclusively associated with female patients but in the late 19th century there were practical as well as emotional reasons why a woman might feel overwhelmingly upset when a promise was broken or affections not returned. A single woman from a wealthy background could live comfortably with a sibling’s family in the role of ‘maiden aunt’ but a poor woman would be forced into domestic service of some kind. And few women of any social status would have chosen to remain unmarried in the Victorian era when the ideal woman was a wife and mother.

The asylum records reflect this state of affairs. Fewer married female patients are recorded as having an occupation and were likely to be identified by their husband’s occupation, for example ‘wife of an engine driver’ or simply as ‘a respectable housewife’.

Margaret Rees, a former domestic servant, was thought to be suffering from ‘a species of Old Maid’s Insanity’ [20] when she was admitted from Bala Workhouse. The symptoms which prompted this diagnosis included the use of obscene language with delusions about men coming to her room at night. And Dr Cox’s description of her as an ‘old fashioned little woman’ suggests his assessment may also have been influenced by a centuries old stereotype!

Margaret is the only female patient whose single status was so explicitly pathologized but fear of becoming an ‘old maid’ may have underpinned the distress felt by other female patients whose insanity was thought to have been triggered by ‘love disappointment’. In the 25 years from 1875 to 1899, where an exciting cause was recorded, ‘love disappointment’ was the third most common cause of insanity in single women, after ill health and general unspecified anxiety.

Catherine Beck was approaching middle age when she was admitted to the asylum convinced that she was married to a Mr Vallance. She had been very friendly, if not engaged, to Mr Vallance twelve months earlier. They had quarrelled and since then there had been no contact between them but her sister-in-law had found Miss Beck walking about the house at night looking for Mr Vallance.[21] Living as housekeeper to her brother and family in Upper Bangor at 40 perhaps she saw Mr Vallance as her last chance of becoming a ‘respectable housewife’ with her own home.

In the rural communities of North Wales, a couple’s suitability for marriage might be tested by ‘bundling’ where the courting couple would spend a night together in the girl’s bed – each wrapped in a separate sheet or separated by a ‘bundling board’. The practice would no doubt intensify sexual desire between a compatible couple but add to the disappointment and humiliation of a girl whose partner changed his mind.

Annie would like a word

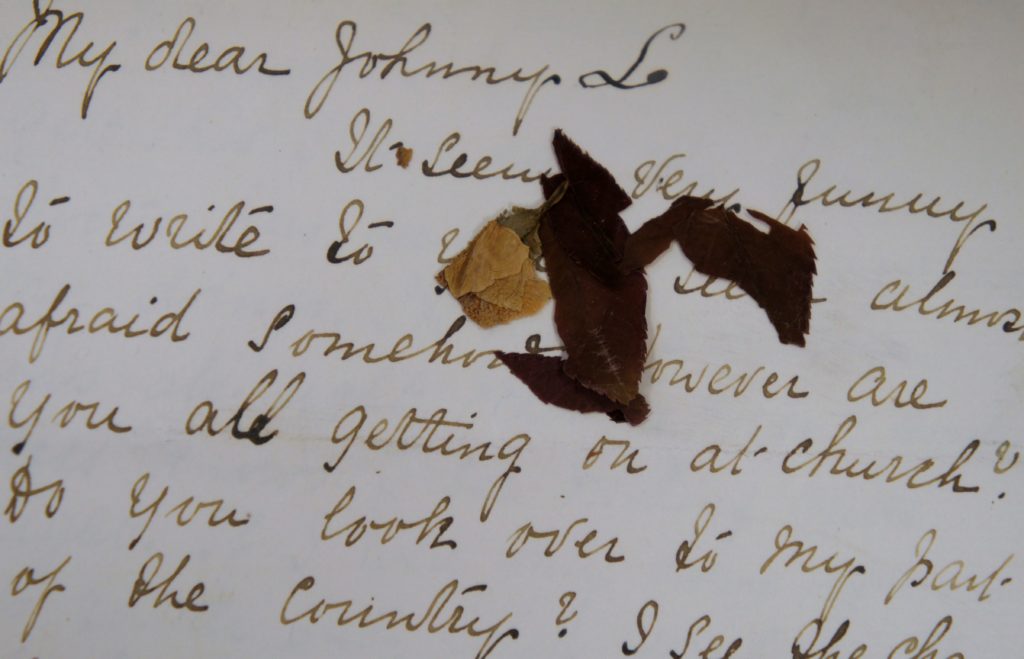

It is unlikely that Ann Beatrice Ward (511), the daughter of a high ranking army officer, would have been ‘bundled’ into bed with Dear Johnny. In any case, she felt their compatibility had been tested and ordained in heaven:

‘Although he (Mr Williams, her music teacher) has never proposed to her, she knows it thro’ a particular hymn which she hears in church’.

A letter to Dear Johnny, dated July 1890, containing pressed rose petals, suggests the hymn might have been ‘Abide with me’.

It seems very funny to write to you. I seem almost afraid somehow. However are you all getting on at church? Do you look over to my part of the country? I see the chancel ever so much. I don’t know how you would feel or what you would do if you were here. Do you remember “Abide with me” when you came in at the end of the sermon and the text was “He sighed”. Something is the matter. I seem to be in your hands. Pa don’t seem to be in a hurry to take me from here for what reason I don’t know. It must seem strange to you. I feel inclined to cry very much. I do cry. Will you get this I wonder.

The senior doctor has been here to overhaul my doings. He said something was all right. What he meant goodness knows. I see nothing quite right. If I were only home again – it is rather sad when you come to think of it, being in an asylum without knowing the reason for what I am here. “Thou fool”, investigate the matter, the root is truth. Christ before Pilate. “What is Truth?” TRUTH is the UNION OF TWO BODIES. ANNIE would very much like a word.

Ann is described as ‘a selfish and self-willed girl’ and when her father came to collect her for transfer to Portsmouth Asylum in 1891 her case notes record that ‘none regrets the step he is taking’.

The things that people do in books…

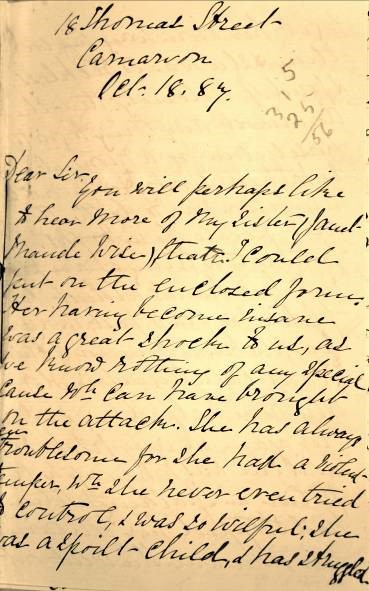

Another self-willed young lady, governess Janet Maude Wise was inspired by the novels she read to take a more adventurous approach to her search for a husband.[22] She was brought to Denbigh from Lincoln County Asylum, where she had been taken after ‘stalking’ a young lawyer in Spalding and being sentenced to 14 days in gaol for vagrancy. In response to Dr Cox’s request for a more detailed patient history, Miss Mira A Wise wrote that her sister had been a constant anxiety to her family in Caernarfon ever since she was a child.

You will perhaps like to hear more of my sister (Janet Maude Wise) than I could put on the enclosed form. Her having become insane was a great shock to us, as we know nothing of any special cause wh. can have brought on the attack. She has always been troublesome for she had a violent temper which she never even tried to control, and was so wilful. She was a spoilt child and has struggled……to get her own way in everything. She was so reckless and fond of notoriety that she would do almost anything to gratify herself, even for a moment, and to be talked about. Her favourite ambition was “to do the things that people do in books”. Unfortunately, things have played into her hands almost completely for years past, in every way; she has a number of chums (I can’t call them friends) here who have helped her and would help her again in any fix. So that until she was taken up by the police in Spalding nothing had stopped her following her own way. She went out as a governess five years ago last May; had some very good situations but was sent away from them at a few hours notice; from the first for ill temper. She lost her last situation of that kind a year ago last March and after that was I believe (but am not sure) a housemaid and possibly a nurse in 2 or 3 places in and about London until she went to Spalding in August 1886. An uncle of ours went to see her there and started her from Peterboro for home, but she changed her ticket at Rugby and went back. Than at the end of September my father went for her, but she wd. not come. She had a great fancy for a young lawyer there and said “she had promised him to stay there until they were married”. The doctor of the Union there told my father that it was a “monomania” she had but that she was not bad enough to be sent to an asylum. She had run after first one man and then another for 9 or 10 years past both here and elsewhere. Vanity seemed to be the cause of her doing so; but so far as we know, she had never before followed any of them about as we hear she did in Spalding. Still they were always in her mind. She used to plan and moider about the man she liked for the time being, wh. was of course very bad for her. We heard that she slept in the Church porch in Spalding either 2 or 3 nights last year and was wandering all day, I fear with little or no food. The clothes she left there have come home and there are both boots and shoes with scarcely any soles left, she had evidently had her feet wet constantly. It is nearly 3 years since she was last at home. She used to be very strong and healthy; but if she had any illness, she used to be very ill. Between 8 and 9 years since she had inflammation of the bowels (brought on by a thorough wetting) and nearly died, after than she used to suffer from constipation. For many years, her temper was almost unbearable at the time she was unwell, especially if she was not sufficiently so. She has suffered a great deal from neuralgia and had 2 or 3 times a gathering in her head, wh. was very painful, and large quantities of matter and blood ran thro’ her nose from it. I thought perhaps they were from poverty of blood as we had been very poor for many years and were consequently ill fed. My father is very healthy and strong and has always been so. My mother was delicate but there was no actual disease in her family. An aunt of my mothers was very wild in much the same way that my sister was, but she is strong and healthy tho’ nearly 80. My sister was very untruthful and wd. tell any lie to gain her own ends, and as she expressed it “get people on her side” and to try and astonish people. She has been a constant anxiety to us ever since she was a child. I shall be very much obliged if you will kindly let me know how she is and what you think of her.

Yours Truly

Mira A. Wise

Janet’s Denbigh case notes describe her as deluded, often abusive and difficult to manage – at one point she asked the doctor to “cut a piece off her tongue as she cannot control it” – and she remained in hospital until her death in April 1913.

Unfit for marriage

Elizabeth Grace Jones had clearly not enjoyed an easy, self-indulgent life before being admitted stuporose to Denbigh from Bala a few years later.[23] Aged 29 she had kept house for her father for some years before becoming engaged to a young man. When her father died, her intended husband kept on the house and a date for the marriage was announced. But shortly before the date he changed his mind and refused to marry Elizabeth because she was ‘too weak’ and a few days later she became insane, threatening suicide and getting out of her bed at night to ramble in the fields and along the riverside. At which point the heartless young man packed her off to the workhouse. When Elizabeth was examined on admission to Denbigh she was found to be consumptive and she died from tuberculosis, quiet and manageable, just six months later.

…OR FOR WORSE?

The Denbigh records show that for every woman ‘disappointed in love’ another woman would be admitted with a condition attributed to an unhappy or abusive marriage. It is often a matter of reading between the lines although sometimes noted quite explicitly as in the case of Ellen Owen from Holyhead whose hospital notes state that her mind had become deranged owing to her intemperate husband’s ill-treatment of her.[24]

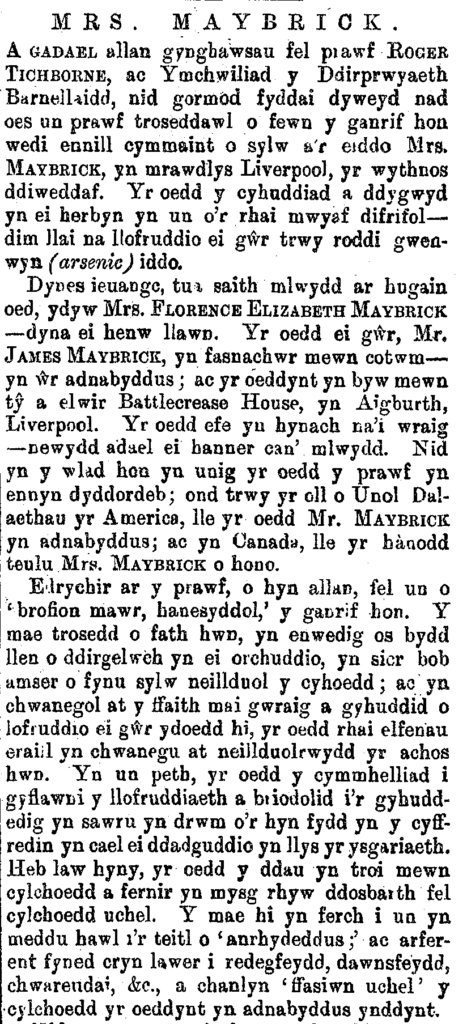

So it may not be surprising that Florence Maybrick, who was tried in Liverpool and sentenced to death for poisoning her abusive much older husband, attracted so much attention in North Wales during the summer of 1889 (see ‘Death Sentence for Immorality’).

Margaret Jones from Deganwy, admitted for the third time in 1890, was not the only female asylum patient to make sympathetic reference to Florence Maybrick and her claim that ‘but for her Mrs Maybrick would have hanged’[25] suggests she was one of the many thousands of people who signed petitions demanding a reprieve.

As well as the Liverpool daily newspapers, which circulated in North Wales as they do today, local Welsh newspapers like Y Baner ac Amserau Cymru (above) kept readers abreast of every development in the case.[26]

And Bangor was one of the first cities in Britain to organise a petition to save Mrs Maybrick from the gallows.[27]

Mrs Maybrick claimed in her defence that she had made the flypaper solution believed responsible for James Maybrick’s death in order to soothe ‘an eruption of the face’ before attending a forthcoming ball. A Bangor chemist, Mr Jones, testified to the court in Liverpool that ladies often came into his shop to buy flypapers, when flies were not in season, to prepare a face wash from the arsenic they contained (see also ‘A complexion to die for!). Not surprisingly sales of fly papers plummeted after the trial and The North Wales Chronicle reported the observation of a druggist ‘in a large way of business’ that: ‘People are afraid to have them in their houses – especially ladies.’[28]

Margaret Jones (4185) and her sister Jane, who was first admitted in 1897, may have felt a special affinity with Mrs Maybrick because their hospital notes suggest they had both suffered at the hands of men. Margaret’s respectability had been compromised by the birth of two illegitimate children and she was, according to the asylum doctors, ‘in need of a change of life’ while dislike and mistrust of her husband is a thread which runs through a succession of Jane’s case notes.[29] For further details of Margaret Jones’ story see ‘Secrets Set in Stone’.

While the rural communities of North West Wales were avidly following developments in the Maybrick trial a series of gruesome murders further afield were also attracting attention and supporters of Mrs Maybrick, whose conviction was based on doubtful scientific evidence, were angered that while she was waiting at Walton Gaol to be hanged, Jack the Ripper remained at large after claiming his sixth victim.

It was Jack the Ripper who inhabited the delusions of Maggie Catherine Williams, an assistant school mistress from Caernarfon, whose melancholia was attributed to the shock of learning that her ‘intended’ had become insane. ‘She saw Marwood ‘The Executioner’ passing the house several times…believed ‘Jack the Ripper’ was in the house’.[30] (See ‘If Pa killed Ma, who’d kill Pa? Marwood’).

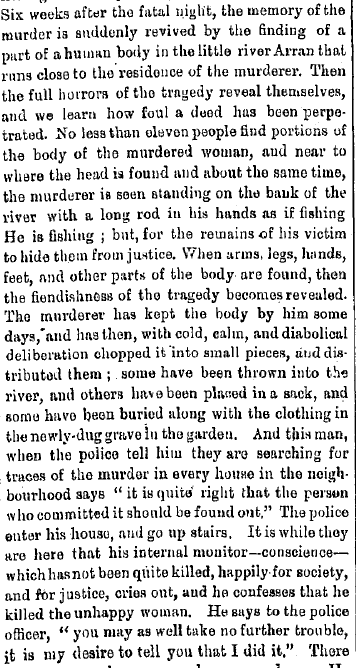

However, if reports of Jack’s horribly mutilated victims sent shivers down the spines of newspaper readers, Whitechapel was a reassuringly long way from North West Wales. In 1877 Elizabeth Roberts’ concerns lay very much closer to home. She lived close by the River Aran in Dolgelley where the body parts of Sarah Hughes had drifted after she had been clubbed and dismembered by her married lover. Cadwalader Jones confessed, after being found trying to retrieve the body parts from the river with a fishing rod, and was hanged for the murder but not before Elizabeth, in constant fear of some harm coming to herself or her children, had begun to find her home intolerable and became depressed and suicidal.[31]

An extract from one of the many reports of Sarah Hughes’ gruesome murder which appeared in the North Wales press and which was thought to have contributed to Elizabeth Roberts’ asylum admission in 1877. The courtroom was packed when the trial of Cadwaladr Jones was opened and according to another report: “Women and children caught in this crowd…were in great danger of being trampled underfoot”.

Moral Madness

References to immorality abound in the Denbigh case notes and it is fair to assume they refer to sexual immorality – ‘accuses the Supt of immoral practices’, ‘believes everyone is accusing her of immoral actions’, ‘uses immoral and obscene language’. Yet sexual intemperance was not listed as a moral cause of insanity. It was categorised as a physical cause along with intemperance in drink and ‘self abuse (sexual)’.

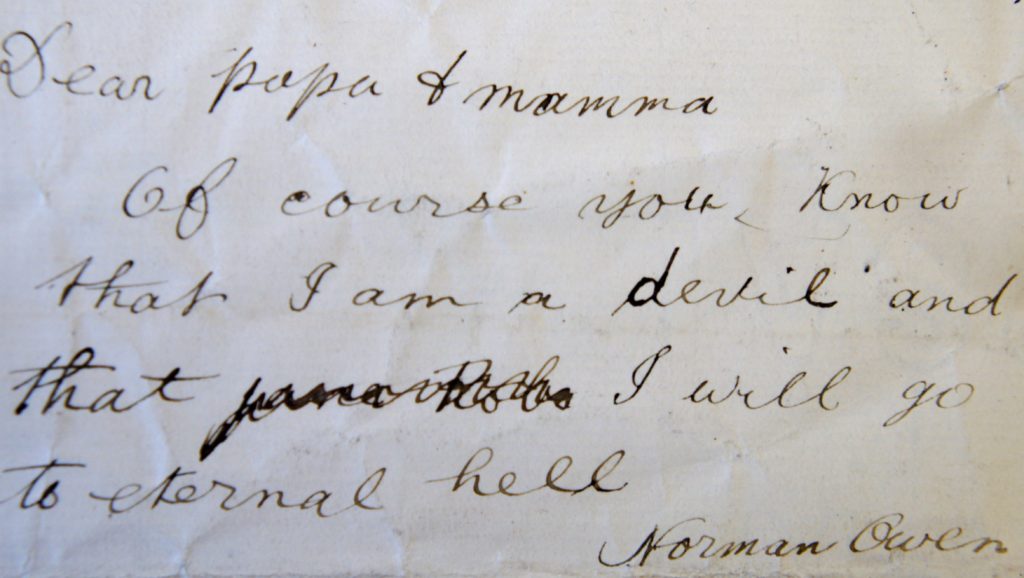

The first time that masturbation was written up as a cause of insanity was in 1885 when it was believed responsible for ‘anergic stupor’ in a 22 year old quarryman admitted with dementia.[32] But by 1890 reference is made to the ‘Insanity of Masturbation’ and Philip Asaph Norman Owen (514), 19, was described as a typical example:

‘Patient is a gawky pale and pasty faced lad with a shambling gait. He during the first day after admission would at times become somewhat communicative and his conversation was free from delusion but displayed the usual religious sentimentalism and ideas of an egotistical nature which are characteristic of the disease… Is in a condition of stupor and stands in the same place or paces about the ward head hung down…’

Philip Owen showed a marked antipathy towards his parents accusing his father, a vicar at Bala, of being a ‘whited sepulchre’ and his mother of being ‘no better than she should be’. He wrote several letters to them which were never sent but kept on record as evidence of his insanity.

At a later point he expressed regret for having spoken ill of his parents and was glad to hear the letters he had written ‘when bad’ had not been posted.

The quality of letters written home were often used as an indication of whether a patient was ready for discharge so that Hannah Roberts, admitted from Pwllheli Workhouse in 1876, left the asylum soon after it was noted that she had ‘written some very good letters’. In contrast, Elizabeth Thomas, admitted from Anglesey in 1889, was being considered for discharge when she wrote a letter which indicated that there was ‘still some perversion of the woman’s reasoning faculties’ and it was thought advisable to detain her for a while longer.[33]

Welsh Water for Argentina

Emigration continued to be blamed for asylum admissions and in 1890 John Jones (4175) was described as ‘very strange in his mind’ after spending a year in America. However, the records from this period also provide an insight into Welsh emigration to Argentina.

William Robert Thomas (525), a merchant from Amlwch, appears to have been amongst the earliest emigrants to Buenos Aires where he was well placed to take advantage of developing trade between Welsh settlers in Patagonia and the outside world. He spent more than 23 years in Denbigh, described as a case of ‘circular insanity’ with alternating periods of depression, excitement and lucidity, and he died there in 1914.

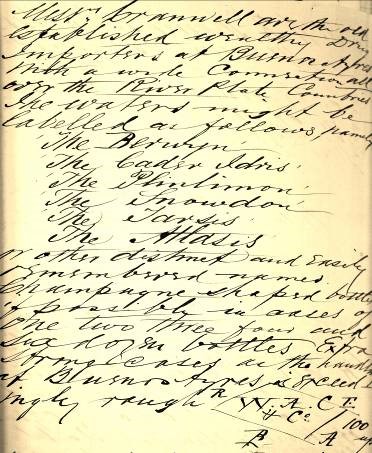

The records indicate that for much of his time in hospital William Thomas remained preoccupied with business, fearing that business rivals in Argentina would make capital out of his absence, and attached to his case notes are letters, orders and what appear to be plans for new enterprises (to view William Thomas’ case notes click here).

For the most part these are illegible but an order for ‘A small shipment of Cheap Carpets for Sale to Juan Barreiro & Co of Buenos Ayres’ addressed to William Evans & Sons of Bangor can be identified along with an order for ‘Welsh Cattle’ from Colonel Platt c/o Mr Thomas of Brynddu, Anglesey.

William Thomas also had plans to bottle and sell mineral waters from Ruthin, England (!) and and some of the labels he envisaged for the waters – ‘The Berwyn’, ‘The Cader Idris’, ‘The Plinlimon’, and ‘The Snowdon’ – might fit nicely into today’s Welsh bottled water market.

His notes read:

Messrs Cranwell are the old established wealthy Drug Importers at Buenos Ayres with a wide connection all over the River Plate Countries.

The waters might be labelled as follows namely

The Berwyn

The Cader Idris

The Plinlimon

The Snowdon

The Tarsis

The Atlasis

or other distinct and easily remembered names. Champagne shaped bottles if possible in cases of one two three four and six dozen bottled. Extra strong cases as the handling at Buenos Ayres is exceedingly rough…

Each bottle to be labelled in the same manner as champagne, black letters on

white ground…also to accompany the shipment 120 Posters or Placards 36 inches x 28 inches or thereabouts with the following: Aquas Minerales Incomparables de las Fuentes de Ruthin, Inglaterra.

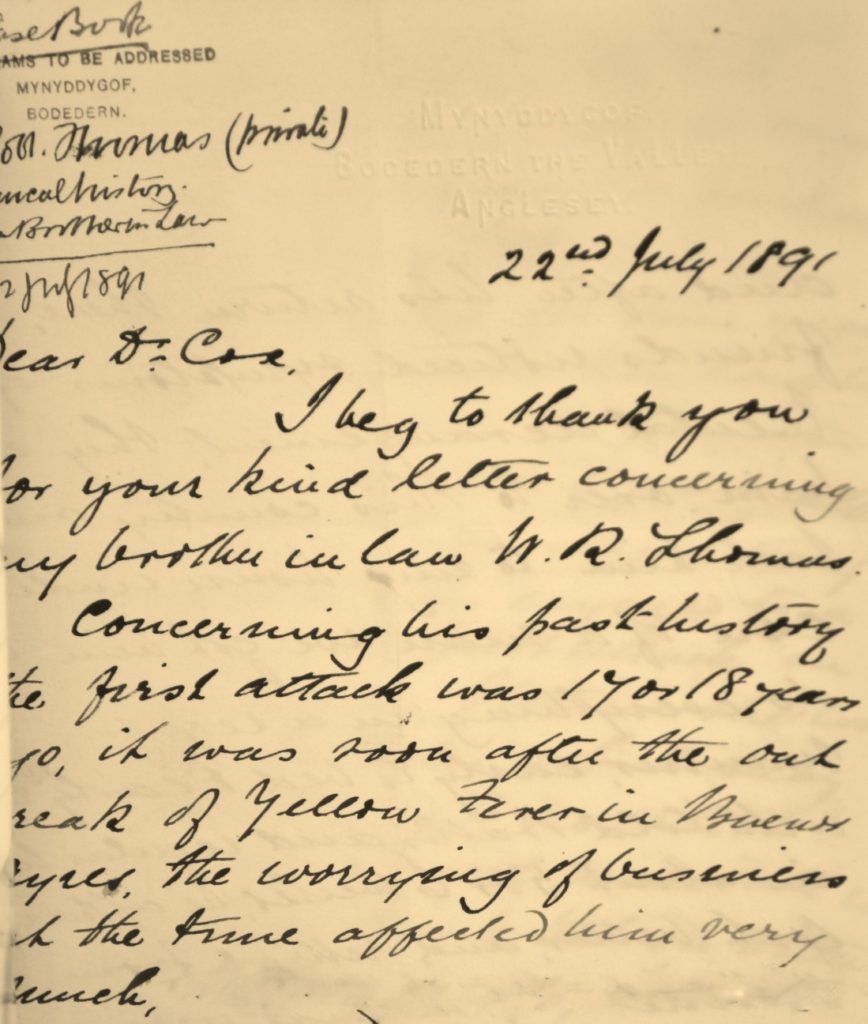

A letter to Dr Cox from the patient’s brother-in-law, Edward Parry, provides a comprehensive history.

(continued)…………….he had partners but they did not take much of the responsibility and soon after he came over to this country, he appeared to me rather unhinged in his ideas, very excitable, high notions of himself. He travelled over Europe and again returned to South America and after his return there his friends noticed symptoms of mental derangement. They sent him over to this country and I took him to my house under the care of a man, we got him to do everything in a regular manner, early to bed and early rising with cold baths and regular meals and in about 5 or 6 weeks he apparently got better and retired from business by mutual arrangement with his partners. He stayed at home for some time, but again got anxious for business and returned to London where he commenced a Commission Agency between this

country and Buenos Ayres, believing that would be less worrying, but he had to travel between the two countries very frequently, he succeeded very well, but there was a peculiarity in him at times, but he continued the business for some years.

I am not quite sure how long he has suffered from the present attack, possibly 4 or 5 years although he had lucid intervals. I may state that he was engaged to a lady before the first attack in Buenos Ayres. I believe she was a Roman Catholic which may have something to do with it. He has been a most moderate man as regards drink but on other points I am not prepared to answer – he was always a most ambitious young man, nothing short of a large fortune, proud, and a very jovial man. He is not now connected in any business and the yarn he speaks about it is a delusion. Latterly he had a tendency to wander at large, to be cruel and very jealous and his talk very rough and unkind, hinting that he would do something worse. During the lucid intervals he knew all that had passed and appeared very depressed and sorry for what he had said and done. The hereditary taint is very slight, I believe a brother of his grandfather became an Imbecile due to some misfortune in connection with marriage. Thanking you again for taking such interest in his case and hope you will be able to give a good report in due time.

With very kind regards,

I am, Dear Sir, Yours Truly,

Edward Parry

It seems the patient’s first attack was 17 or 18 years earlier, ‘soon after the outbreak of Yellow Fever in Buenos Ayres’. Yellow Fever raged in the city during 1871 – only six years after the first settlers from Wales arrived in Argentina – and Mr Parry’s letter suggests that William Thomas was already settled there by this time with established business partners. While worries about business during the epidemic were thought to have affected his brother-in-law badly, Mr Parry offers a further explanation:

I may state that he was engaged to a lady before the first attack in Buenos Ayres. I believe she was a Roman Catholic which may have something to do with it.

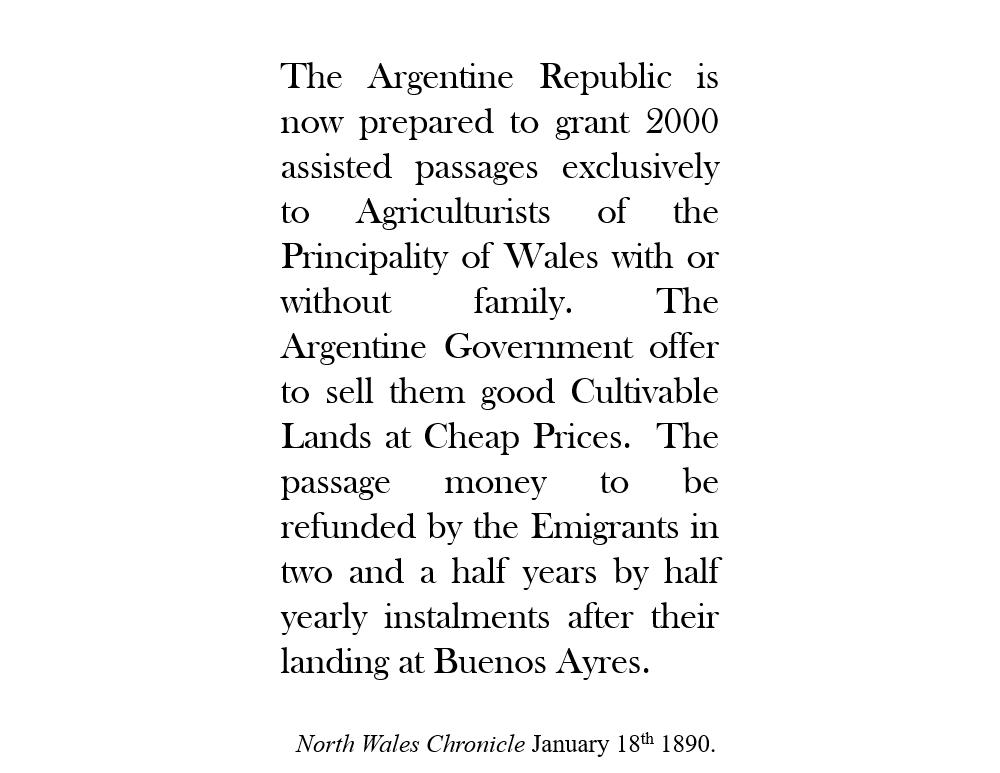

By 1890 the Welsh settlement in Patagonia was thriving and the Argentine government was keen to attract more immigrants, who were provided with food and lodgings in Buenos Ayres until they could be conveyed to the colony in Chubut. In January the North Wales Chronicle carried a paragraph headed EMIGRATION TO THE ARGENTINE REPUBLIC in which it was reported that:

William Thomas’s face is recorded as ‘much tanned’ and in 1890 it was thought that over-exposure to the sun carried the risk of subsequent insanity. This was not noted as a contributory factor in his case but theories circulating around this time linked sunstroke to the insanity of emigrants to the Americas and sailors and soldiers serving overseas and may well have influenced the diagnoses of Dr Cox and his assistants. Dr Theo. B. Hyslop’s paper Sunstroke and Insanity was presented to the Medico-Psychological Association in 1890 and in that year five of the male patients admitted to Denbigh were recorded as having become insane after an attack of sunstroke. Three had been affected in America and one, a sailor, during a voyage to India.

Moses Williams of Llanfairfechan, the fifth man whose insanity was attributed to sunstroke, was diagnosed with GPI (general paralysis of the insane).[35] Dr Hyslop quotes a Dr Mickle who ‘believes that sunstroke is not uncommonly a cause of general paralysis among British soldiers in India’. And while not prepared to define precisely the relationship of syphilis to sunstroke he claims that ‘undoubtedly syphilis precedes attacks of sunstroke’.[36] At this point, whatever suspicions there may have been that a link existed between syphilis and GPI, sunstroke seems to have clouded the picture.

1890 Lunacy Act

The 1890 Lunacy Amendment Act was intended to consolidate procedures for the admission of lunatics but was not welcomed by medical and clerical asylum staff. R. Percy Smith, Royal Bethlem Hospital, condemned the Act as ‘specially framed…to drive Superintendents of Asylums and Hospitals to Madness’. [37] And in his annual report, Dr Cox referred to the increased workload imposed by ‘numerous additional returns of medical and statistical nature’ required by the Commissioners.[38] A strict new system of certification meant that several patients were admitted to Denbigh in 1890 with incomplete or incorrectly completed papers and they had to be sent into town for new orders to be signed.

Among these patients was the 15 year old boy John Warrington (503) who was brought to the asylum from the Clio, an industrial training ship moored in the Menai Straits, with a certificate signed only by the ship’s doctor (see ‘Clio Training Ship’ for more information).

It is tempting to see John Barker’s note that the patient ‘was brought here…at the time that the Com. in Lunacy were making their visit’ as an indication that the asylum staff might not ordinarily have been quite so keen to have all the boxes ticked!

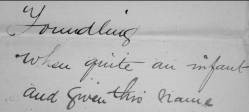

Like most of the boys aboard the Clio John was an orphan, whose name was taken from the town of Warrington where he was found abandoned soon after birth.

Sent to the ship at the age of 12 because he could not be kept in school – “would rather be rambling, having on two occasions rode on the Buffers of an express train for miles”[39] – he is described on the warrant as mischievous but honest and very kind-hearted. John’s asylum case notes suggest that he was not benefited by the three years he spent aboard the Clio.

Dr Cox decided fairly early on that the boy was not insane but noted:

There is an absence of self control – a lack of knowledge of right or wrong – and very likely an inherent predisposition to vice and laziness as evinced by his intolerance of all forms of discipline. He is a boy who if left to his own devices would, through laziness and his animal propensities, very soon prove a danger to the community.

However, John would not prove a danger to the community in North Wales. He was discharged back to the Warrington Union 2 months after his admission to Denbigh along with the prediction that he ‘will never do well at anything’.

Richard Jones, 18, from Blaenau Ffestiniog was one of the relatively few boys from North West Wales who found himself on board the Clio. Admitted to the asylum in 1902 with a diagnosis of moral insanity, he remained in care for the following eight years. Described by Dr Herbert as a ‘most intelligent youth except that his appreciation of right and wrong is deficient’, Richard settled into the hospital routine well, working daily and promising to turn over a new leaf. However, within a few weeks he was found trying to hang himself by his scarf from the top of the bedstead and later told an attendant that it was fear of being sent home which had prompted the attempt. Richard’s reluctance to return to Blaenau Ffestiniog was matched by his father’s reluctance to have him home. Richard Jones Snr, a butcher, was ‘not very anxious to have him but…would see him when he (the patient) is 21 years’. Useful and well behaved, the young man was kindly treated at Denbigh, played tennis regularly with Dr Herbert and was entered for and passed a First Aid Ambulance examination. His father was eventually persuaded to take him home on trial but returned him before the time was up and Richard remained in the asylum for another four years. Dr Herbert’s frustration is evident in the case notes: ‘Has grown up and should be taken home by his father’.[40]

Annum difficile

1890 was a difficult year. Since the 1870s patient numbers had been steadily and continuously increasing and acutely ill patients were being admitted to an asylum already full of chronic cases who were unlikely ever to be discharged. By 1890 any patient who could possibly be discharged to family or workhouse had already left. In 1889 the House Committee had presented a report recommending an extension and this marked the beginning of a long and bitter dispute with the Commissioners in Lunacy who favoured building an additional asylum elsewhere.

To make matters worse the pneumonia and Russian ‘Flu epidemics at the beginning of 1890 resulted in an unusually high patient mortality rate. And because attendants were also falling sick the existing problems of understaffing were exacerbated. Overcrowded, fractious patients (lack of space was thought to be responsible for more than a few black eyes[41]) – and overworked staff almost certainly led to an increased use of restraint and seclusion.

In addition to these difficulties the medical and clerical staff had to deal with a whole new level of bureaucracy imposed by the 1890 Lunacy Amendment Act.

Against this background it is not surprising that case notes fell somewhere short of perfect. Fanny Lloyd (4140) was admitted in January 1890 but her first case note is dated March:

No notes of patient’s condition were made at the time of her admission owing to the pressure of work consequent upon the epidemic of Pneumonia then raging. Consequently in this and most of the cases admitted during the last 3 months but very meagre notes will be found tho’ they were examined and treated as usual but there was no time to record the same.

Yet the case notes still convey a sense that each patient’s condition and background were given careful consideration. Perhaps the medications were not always carefully written up but it appears patients were seen regularly and that medical staff came to know them well enough to make personal comments about them as well as reporting any improvement or deterioration. ‘A well behaved and a very decent fellow in every way’ was Dr Cox’s description of Hugh Robert Williams (4166) who firmly believed he was the Queen’s son and had been born in Windsor Castle. And Jane Roberts, a blacksmith’s wife admitted with puerperal mania (4145) was a ‘very nice little woman’.

The notes also suggest that the doctors had conflicting views about sending their ‘relieved’ patients to the workhouse to make space in the asylum. While it was thought Rowland Rowlands (4190), ‘a very harmless and well conducted old man’ would do well in a workhouse, Margaret Jones (4203) was considered ‘a striking example of the superiority of Asylum to Workhouse life’.

What is apparent from the 1890 notes is that the staff at Denbigh, despite being overworked and having to endure constant criticism from the Lunacy Commissioners, had a genuine interest in the people who came into their care. This was not assembly line medicine.

Read more ‘1905‘.

Footnotes

[1] 30th Annual Report 1878, Medical Superintendent’s Report

[2] Cited in Pam Michael, chapter 7, page 88 – The gossiping Guide to Wales.

[3] 41st Annual Report 1889, Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy.

[4] 41st Annual Report 1889, Report of the House Committee as to the Necessity of Increased Accommodation.

[5] Anglesey Record Office/WG/3/19/Letter to Bangor and Beaumaris Union

[6] 42nd Annual Report 1890, Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy.

[7] 42nd Annual Report 1890, Medical Superintendent’s Report.

[8] North Wales Chronicle January 25th 1890.

[9] DRO/HD/1/363/Case no. 454

[10] DRO/HD/1/331/Case no. 2477.

[11] DRO/HD/1/363/Case no. 3695.

[12] DRO/HD/1/336/Case no. 3978.

[13] Doyle, D., Per rectum: a history of enemata, J R Coll. Physicians Edinb 2005; 35; 367-370.

[14] 42nd Annual Report 1890, Medical Superintendent’s Report.

[15] The first successful use of ether as an anaesthetic in NW Wales was at the Penrhyn Quarry Hospital, Llanberis in 1847, less than three months after the announcement of its discovery reached London. Chloroform was discovered the following year. In O V Jones (1984), “The Progress of Medicine: A History of the Caernarfon and Anglesey Infirmary 1809-1948, pp 66-67.

[16] DRO/HD/1/360/Case no. 2424

[17] DRO/HD/1/Reception Order?/Case no. 2411.

[18] Hare, E (1981) The Two Manias: A study of the evolution of the modern concept of mania, Br J Psych; 138; 89-99.

[19] DRO/HD/1/336/Case no. 3896

[20] DRO/HD/1/337Case no. 4263

[21] DRO/HD/1/335/ Case no. 468

[22] DRO/HD/1/336/Case no. 3890

[23] DRO/HD/1/340/Case no. 4944

[24] DRO/HD/1/337/Case no. 4104

[25] DRO/HD/1/341/Case no. 5233

[26]Y Baner ac Amserau Cymru (Denbigh), August 14th 1889, Issue 1684.

[27] Daily News (London, England), August 12th 1889, Issue 13525.

[28] North Wales Chronicle, January 18th 1890.

[29] DRO/HD/1/Case nos. 452 and 5458 respectively

[30] DRO/HD/1/340/Case no. 5135

[31] DRO/HD/1/331/Case no. 2746

[32] DRO/HD/1/363/Case no. 3640

[33] DRO/HD/1/Case nos. 2543 and 4051 respectively

[34] North Wales Chronicle January 18th 1890.

[35] DRO/HD/1/367/adm no. 4369

[36] Theo. B. Hyslop, MD, Sunstroke and Insanity, British Journal of Psychiatry (1890) 36 : 494-504.

[37] R. Percy Smith, The Working of the New Lunacy Act, British Journal of Psychiatry (1890) 36: 597-599.

[38] 42nd Annual Report 1890, Medical Superintendent’s Report.

[39] DRO/HD/1/366/adm. no. 503

[40] DRO/HD/1/372/adm. no. 647

[41] 37th Annual Report 1885, Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy