In 1905 Denbigh Asylum was effectively a building site. An isolation hospital, additional wards for long-stay female patients, an up-to-date laundry, kitchen and dining room, new staff accommodation and a refurbished administrative block had all been completed and yet the struggle to provide safe, sanitary accommodation for patients looked set to continue. There were still more patients than beds and a further phase of building had already begun.

In light of this the old debate, begun fifteen years earlier, about whether it would be wiser to build a second asylum for patients from North West Wales rather than persist with efforts to expand the existing building was raised again. This time, at a special meeting between members of the asylum committee and Carnarvonshire County Council, it was resolved at least to consider a new asylum.[1]

One of the few pleasant spin offs of a seemingly endless building scheme was that Messrs Jones and Sons of Liverpool, the builders contracted to complete the extensions, lent out their traction engine for the patients to be taken on trips and picnics. In June 1904 more than 100 patients visited Bryntrillyn ‘conveyed thither in brakes, and trucks drawn by the traction engine’ and spent the day walking in the surrounding hills.[2]

Musical evenings

Dr Cox and Dr Herbert had remained in post for more than twenty years and this continuity of medical staffing may have gone some way towards making any disruptions caused by the building work more bearable. Concerns for ‘the general contentment and moral discipline of the insane’ also continued to inspire a range of evening entertainments. Patients were taken into town for concerts and theatrical productions and with the appointment of Dr Frank Jones as Assistant Medical Officer in 1902 in-house entertainments were given a new lease of life. A talented musician himself, Dr Jones helped Dr Herbert to stage a variety of musical events and plays in the main hall of the asylum, including a ‘capital Minstrel Entertainment and farce’.

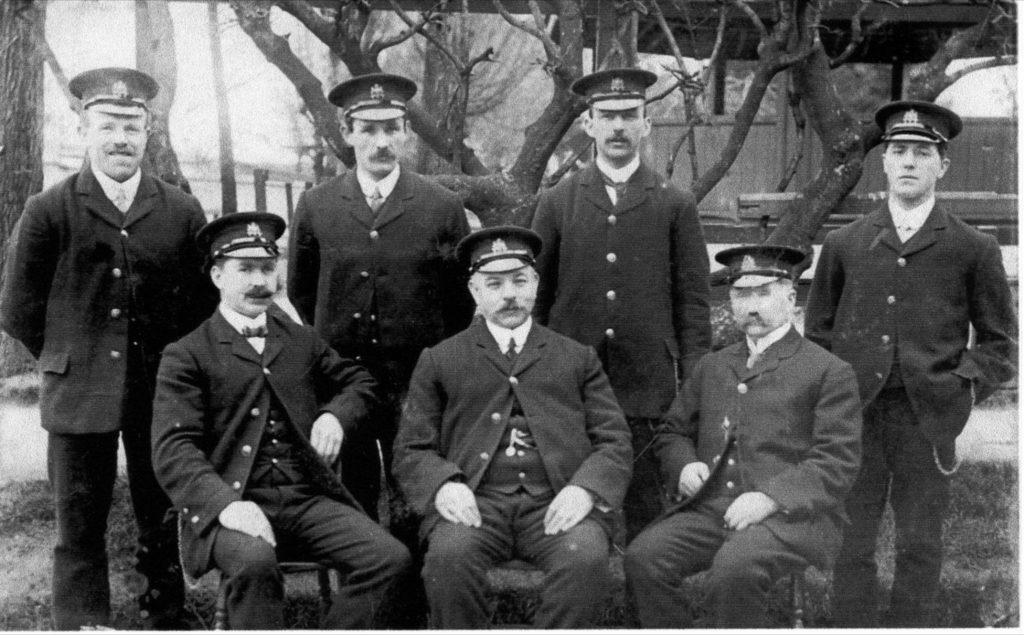

The asylum band established in 1870 still flourished, playing at the weekly dances throughout the year, and smaller ensembles like the group of nurses pictured below with their instruments in the grounds of the asylum were also given an opportunity to show off their skills. There must surely have been very few string quartets which included a banjo!

A winning team

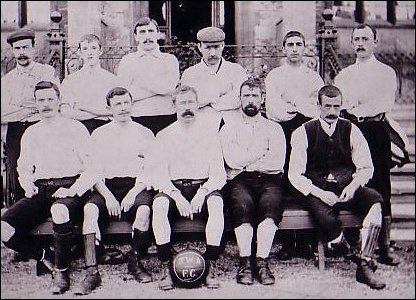

Dr Jones, or Dr Frank as he became known, was also a keen sportsman and patients were encouraged to participate in football matches and tennis parties and in 1905 the asylum boasted this cup winning football team:

A sports day with ‘a liberal supply of substantial and useful prizes many of which were thoughtfully presented by our Denbigh acquaintances’ became a highlight of the summer season which ended with a tea party for patients in the grounds of Denbigh Castle.

The asylum clearly played an important role in the life of the town and, quite apart from the charitable input of wealthy benefactors, this is evident from visits to the asylum by local school children. Children from the National School celebrated Mayday with the patients there in 1905.

In the limelight

During the winter, there were ‘interesting and instructive’ lectures and these included a talk – with lime-light* views – by a former patient, the Rev. Joseph Rhodes, on his work as a missionary in West Africa.[3] The Rev. Rhodes, a Wesleyan minister living in Colwyn Bay, had been admitted to the asylum as a private patient in October 1902, the cause of his mania thought to be an attack two years earlier on his return from Africa where he had contracted malaria. Rev. Rhodes proved a troublesome patient whose condition improved and deteriorated from week to week. Just a few days after ‘a little steady improvement’ is noted, he struck three of his fellow patients. One of them returned the blow:

(Rev. Rhodes) was playing chess today with a patient in No. 3. Another patient happened to disturb one of the pieces when Rhodes slapped him in the face and, in return, got struck on the head by the fist. There is a tiny wound on the right temple.[4]

The minister was discharged on trial in April 1903 ‘relieved’ but, although he recovered enough to deliver his winter lecture, by the summer of 1905 he had relapsed and was readmitted to Denbigh in September of that year (704), his madness on this occasion evidenced by ‘entering a phrenologist’s room and pulling down the pictures from the walls’ and ‘preaching in the open air’. (For further details see ‘Mission to Madness’)

Outings, evening entertainments, lectures and sporting events went some way to maintaining patient well-being but the years 1890 to 1905 represented a turbulent period in the asylum’s history. The Secretary of State had not approved an extension to Denbigh until 1895 and by this time pressure on beds had made it necessary to lease Glan y Wern near Llandyrnog to accommodate convalescing female patients. While some of the male patients had been boarded out to Middlesborough and Derby Asylums.

Peak in patient deaths from tuberculosis

When Dr Cox reported in 1899 that pulmonary tuberculosis (phthisis) had accounted for 26 per cent of patient deaths during the previous year, he attributed the prevalence of the disease to insanitary conditions caused by ‘overcrowding, defective ventilation and drainage, with an impure and unreliable water supply’.[5]

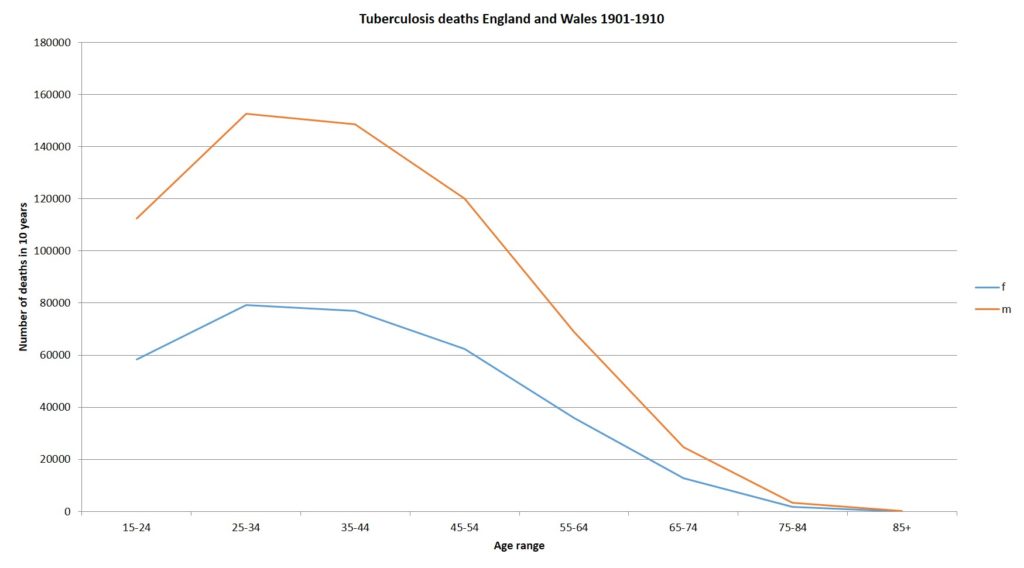

The old water supply was discontinued in 1900 and water piped from the reservoir at Llyn Bran but four years later, despite having clean water, a new sewage system, improved ventilation and ‘continuous efforts throughout the asylum with a view to combating and arresting the development of tubercular infection, to which the insane are especially prone’, it was clear that tuberculosis was not going to go away.[6] In line with national statistics, the number of patient deaths from the disease reached a new peak in 1903/1904.[7]

As the chart above indicates, pulmonary tuberculosis was a disease which primarily affected young people between the ages of 20 and 40 with young men far more susceptible than young women. The difference might be explained by occupation since young men were much more likely to be employed in jobs now known to be related to pulmonary disease such as coal mining and, in North West Wales, slate quarrying.

The beneficial effects of slate dust

However, as late as 1922 Dr J. Bradley Hughes, the Medical Officer at Penrhyn Quarry Hospital was affirming that slate dust was ‘not merely harmless but beneficial’! Dr E. Shelton Roberts had informed him that, during a long acquaintance with the general health of the Penygroes district and the quarries in particular, he had not met with a single case of silicosis or lung trouble among the quarrymen there which was attributable to their work.

Dr John Roberts, a general practitioner in Llanberis, while acknowledging that the percentage of tubercular cases was somewhat high in the three parishes where the quarry workmen lived, said that he considered slate particles to be soft and non-irritant, containing very little silicate and a good deal of iron and sulphur which was a useful germicide.[8]

The asylum case notes suggest that some patients were suffering from tuberculosis when they were admitted and that this may have accounted for the symptoms which brought them there. Eleazor Brereton’s melancholia was attributed to the loss of his wife but he had died from ‘acute tubercule of lungs’ within 6 months of his admission in 1905 (6527). Brought from Anglesey in an excited, agitated condition, Mary Evans had a fever noted within weeks of her admission (6613) and she too was dead within a few months. However, an analysis of long stay patients indicates that the majority of deaths from tuberculosis occurred after 3-5 years in hospital and so the assumption must be that they were infected with the disease while they were in care (see Healy et al, 2012 for further details).

‘Expensive’ remedies for paupers

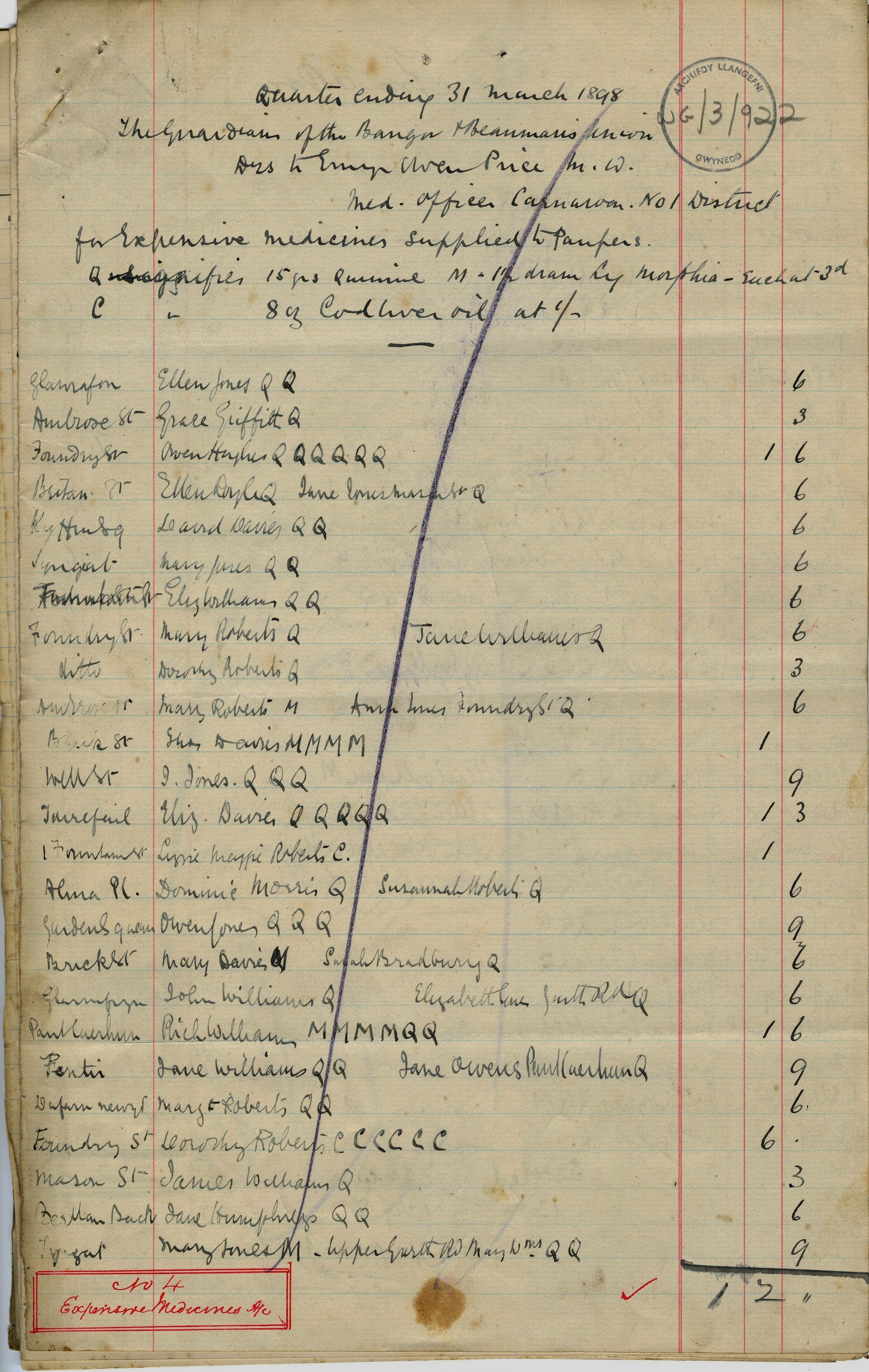

The medication most commonly given to patients suffering with tuberculosis was cod liver oil which was thought to be of value in a wide variety of wasting diseases and in undernourished children. It was not a cheap ‘drug’ in the 19th century and appears on a 1898 account submitted to the Guardians of Bangor and Beaumaris Union by Dr Emyr Owen Price for ‘Expensive Medicines Supplied to Paupers’.[9]

Quinine and Morphia are the two other expensive medicines listed and both cost a mere 3d a dose compared with 1s for a dose of cod liver oil. So that Owen Hughes of Foundry Street, Bangor had 6 doses of quinine for 1s 6d while a neighbour Dorothy Roberts’s 6 doses of cod liver oil cost the Guardians 6s.

Pneumonia was another common cause of death in asylum patients and often followed influenza which continued to plague the asylum and sometimes reached epidemic proportions as it had in 1890. Ellen Ellis’s death 11 days after admission led Dr Herbert to comment:

This poor old woman died today of Pneumonia doubtless due to the Influenza now so prevalent in the house. She used to be quite well up to about four days ago when she suddenly sickened. There have been several similar instances here of late in which patients when admitted have contracted a fatal illness and died within a very short time of leaving their homes; indeed there is no doubt that when Influenza is rife here they run far less risk at home.[10]

Although influenza claimed the lives of several patients in the early part of the year, health problems in 1905 centred around dysentery, as it had the previous year, and strenuous efforts were made to deal with the causes of infection, one of which was a ‘plague of rats…a prevailing source of trouble’ in the older wards.[11] The outbreak was contained by treating patients in the Isolation Hospital.

A laboratory for pathological and bacteriological research was also being ‘used with advantage’ according to the 1904 annual report but what happened to this laboratory is something of a mystery because ten years later Dr Frank Jones was complaining that the asylum lacked both a laboratory and a pathologist. Until 1928 when Dr Ceinwen Evans was appointed to the post of pathologist, blood samples had to be sent to Cardiff for testing.

What an isolation hospital and a new pathology laboratory could not deal with were the pressures placed on asylum staff by unavoidably disruptive building work and patient overcrowding which were almost certainly responsible for a discernible decline in standards of care. In 1904 Dr Cox had to report that a junior nurse had been asked to resign for ill-treating a patient and the Commissioners in Lunacy had insisted on a prosecution. The young woman appeared before the Denbigh Borough Police Court and was fined £2 with costs.[12]

Retaining useful female staff presented particular problems and an exceptionally high turnover of junior attendants and servants was recorded the following year. Along with ‘matrimonial and other domestic engagements’ this was put down to ‘a desire to seek new surroundings or occupation, with the anticipation of more favourable and lucrative positions in similar institutions’. The staff who remained at Denbigh were commended in the 1905 report – with the exception of one male and one female attendant who were asked to resign in consequence of their ‘irregular behaviour’![13]

Hard times

For many people in North West Wales the first five years of the 20th century were especially hard. The communities of the area depended heavily upon slate quarrying for employment and, after a series of recessions and upturns, strikes and lock-outs, the Penrhyn Strike of 1900-1903 led to a permanent depression in the slate industry. Distress was widespread but in Bethesda, where the Penrhyn quarrymen were concentrated, reductions in pay and job losses were only part of the picture. Bitterness between the 500 men who went back to work in 1901 and the 2,000 union men who remained out for another two years lasted far longer than the strike. A letter to the Home Secretary from one of the workers describes how Bethesda became a battleground:

We are molested and intimidated by the men who are still on strike, and their sympathisers…On several Saturday nights now, large crowds have been congregating in the village for the purpose of watching and molesting us and our wives and children… These crowds are most threatening and disorderly, and are beyond the control of the force of the police now stationed here.[14]

As well as fearing for their own safety and the safety of their families the working men, who received an extra pound in their pay-packets for returning to the quarry, were pilloried in strike songs and had to look at notices denouncing them as traitors in the windows of their neighbours’ houses.

It might be expected that such a climate of fear and distress would give rise to an exceptionally large number of hospital admissions from Bethesda and surrounding villages but this does not appear to be the case. Only two admissions from quarrymen during this period were linked to ‘strike troubles’ but it is unclear whether either of the men concerned was directly involved in the dispute. Price Jones, 45, ‘constantly talking about the strike and loss of wages’, had not worked for the previous 7 years owing to ill health and Hugh Price, 69, had been unfit for work seven months before being admitted to the asylum with melancholia.[15] A third admission was directly attributable to the strike. PC William Jones Owen, 27, had left the police force after being frightened by a crowd of strikers while he was on duty by himself in a lonely part of Bethesda and had become depressed and confused as a result. Tormented by visual hallucinations, the young policeman was noted to have a nervous twitching of the face and tremulous hands but whether this was connected to the dementia he was diagnosed with on admission or to alcohol abuse is unclear. According to his case notes, he had been on duty in Bethesda for eight months prior to admission and ‘might have been intemperate there’. A fellow police officer who came to visit him at the asylum confirmed that William Owen had been a heavy drinker at one time.[16]

It would be impossible to overestimate the hardship experienced by the Penrhyn trade unionists but if the strikers were bound together by their cause and the workers or ‘blacklegs’ bound together by their fear then this might explain why a community catastrophe like the Penrhyn Strike was not reflected in asylum admissions between 1900 and 1903.

A Welsh awakening

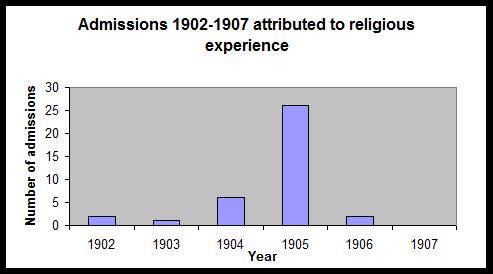

However it has been suggested that the hardships and uncertainties caused by the strike, not only in Bethesda but throughout the slate quarrying communities of North West Wales, made a significant contribution to the Great Religious Revival of 1905.[17] And religious revivalism is a defining characteristic of the 1905 asylum records:

…early in the year an exceptional number of patients were admitted suffering from religious mania, which was attributed in several instances to religious fervour due to the Revivalist movement then prevailing throughout the Principality.[18]

Dr Cox was careful to moderate this opinion by saying that most of the patients affected had a history of insanity or at least a family history and that their consequent ‘impaired emotional and moral sense’ made them especially susceptible to the revival.

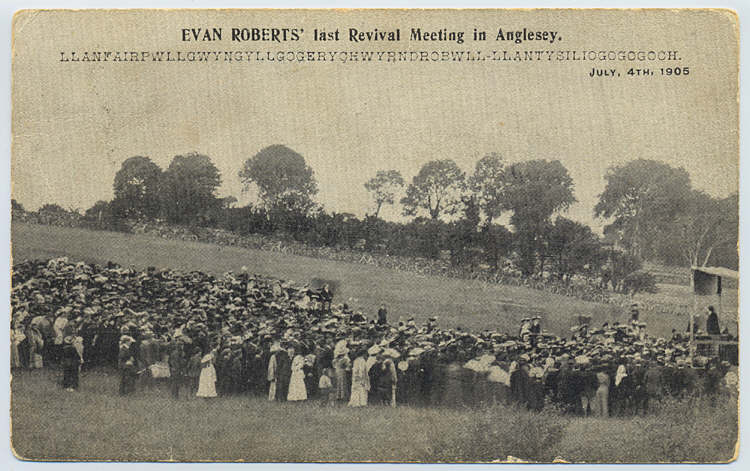

By 1905 the revival movement begun by Evan Roberts at the Moriah Chapel in Loughor near Swansea was in full flow throughout the principality and the North Wales newspapers fed revivalist fervour by running headlines like FIERY VISIONS ON A COUNTRY ROAD, A Carnarvonshire Rival to Evan Roberts and Fervent Meetings in Bethesda, offering illustrated penny pamphlets covering the history of ‘This Marvellous Uprising’. An authoritative statement was sought on rumours that an abnormal number of patients were being admitted to the asylum as a direct consequence of the revival but, like Dr Cox, the Committee of Visitors was keen to play down any link between religious excitement and religious mania insisting that there had been a great deal of exaggeration. (For further information on Evan Roberts and the Religious Revival see ‘If Everyone Went Crazy…’)

However, it can be seen from the chart below that there was an unusually large number of first admissions with an acute psychotic episode towards the end of 1904 and the early part of 1905 with the majority of them linked specifically to a revival meeting.

The admissions often came within days of a meeting and did not signal any further problems suggesting that an intense religious experience can lead to a psychotic episode but not necessarily to a chronic illness. Dr Cox reported early recoveries in those patients whose mental disturbance was related to religious excitement with an average period of residence ranging from 2-7 months for men and slightly longer, 5-11 months, for women (see Linden et al 2010 – Religion and Psychosis: the effects of the Welsh religious revival in 1904-1905).

The mental symptoms in most instances were of an acute character and marked by excessive exaltation and perversion of judgement. It is interesting to observe, however, that the larger proportion of the cases in question have yielded to early treatment, and were recommended for discharge during the course of the year.[19]

This was certainly the case for Mary Williams (6542), described as a ‘respectable girl in service at Carnarvon’, who became suddenly insane after returning home from a revival meeting at her local chapel, shouting, singing hymns and breaking a window. Mary spent three months in the asylum before being discharged recovered. William Jones of Nantlle (6533), afflicted suddenly with acute mania after taking a prominent part in the religious revival – ‘although always inclined that way’ – was also home again within three months and never readmitted.

For a brother and sister from Dolgelley, weaver William Roberts (6470) and farmer’s wife Anne Jones (6491) the outcomes were very different. Both were admitted soon after attending revival meetings but, whereas William recovered quite quickly from his episode of psychosis and was discharged within 12 months, Anne’s condition steadily deteriorated into dementia and she remained in the asylum until her death in 1942 at the age of 78.

Revival meetings also marked the beginning of a lifetime’s illness for a 16 year old butcher’s errand boy from Barmouth, Rowland Griffith Davies (6493) who was admitted to Denbigh at the end of January with religious melancholia. Young people like Rowland were well represented at revival meetings and a sceptical view might be that this was because they provided an opportunity for girls and boys to meet together without the usual parental supervision.

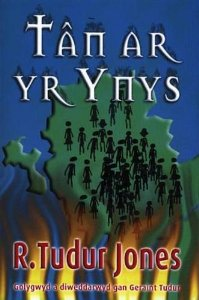

In his book about the revival on Anglesey, Tan ar yr Ynys: Diwygiad 1904-05 ar Ynys Mon (Fire on the Island: Revival 1904-05 on Anglesey), R Tudor Jones compares the revival meetings to hiring fairs where young agricultural servants would gather to meet prospective employers – and each other![20]

Rowland told the asylum doctors that he had attended prayer meetings for five consecutive nights until 2am and that: ‘boys of 10 and 12 years were also there until that hour.’ Dr Cox would have considered the boy one of those patients likely to be ‘perverted by influences of this nature’ because three of his paternal relatives had been insane. Rowland went on to have 12 further admissions to Denbigh with either melancholia or mania and he died there in 1944.

Wish you were here…

Chapels were keen to contain any religious excitement considered excessive. When the ‘hwyl’ of a meeting in Bangor was disrupted by one of the congregation testifying rather too loudly instructions were given to start a hymn and the man concerned had no choice but to join in with the singing.[21] However, while the outburst of one over- excited individual could be controlled by fellow worshippers, police were needed to control a crowd of revivalists gathered in Bangor to object to the dancing at a ball of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers Volunteers.[22]

If dancing was frowned upon then reading novels attracted similar approbation. Evan Roberts singled out some of the young women who attended his early meetings as reckless characters for: ‘Reading novels; flirting; never reading their Bibles’.[23] In fact, the asylum case notes of the period tell us that it was not only young women who read novels. When William Williams was admitted to Denbigh in December 1904 novels were blamed for his acute mania. His notes on admission read: “Was crossed in love 3 years ago. Latterly he has been a great novel reader, chiefly Marie Corelli’s works”.[24] (see ‘Damned By the Critics but Read By the Queen’). A farm labourer from Anglesey, William did not survive tuberculosis long enough to see the Great Revival in full flow and hopefully not long enough for him to feel ashamed about reading his romantic novels which it seems likely had nothing to do with his confused, restless state of mind.

Religious excitement may have contributed to Mary Griffith’s melancholia (6582) but as she had given birth to a child at precisely the time the revival was at its height in North Wales the two factors were thought to be mixed up together. Mary was suicidal when admitted, showed no interest in her baby and would get out of bed only to wander away from home but she recovered quickly and was discharged quite well within three months. This ‘revival’ baby may have been instrumental in Mary’s readmission to Denbigh 20 years later. Mary’s reception order in 1925 has daughter Maggie Griffith stating that her mother had asked her to hire someone to shoot her.[25]

Puerperal Insanity: childbirth or poverty?

It is clear from the Denbigh records that community events like religious revival meetings and personal circumstances like poverty, domestic discord or illness contributed to the insanity of some new mothers. When Mary Owens was admitted ‘wild and maniacal’ from Pwllheli Workhouse in 1876 having torn her clothes into rags and threatened to kill her children, it was noted that her husband had not looked after her well, providing her with only ‘scanty food’ during a troublesome confinement.[26] Elizabeth Hughes, undressed and insane, was found by a neighbour carrying her baby towards the seashore at Llaneilian on Anglesey determined to do away with herself and her child and her notes describe a similar history of neglect during pregnancy, ‘she often went without food’.[27] Catherine Mattinie Jones, an unmarried domestic servant with a ‘Madonna-like countenance’, was thought to be suffering from tuberculosis when she was admitted to Denbigh in 1893 after becoming violent, smashing crockery, undressing herself ‘at irregular and all hours of the day’ and throwing a boot at her baby.[28] And Alice Roberts – a ‘common prostitute about the streets of Holyhead’ – spent the night in an old cowshed before giving birth to her baby in the street. When the police found her eight months later running about the streets naked, cursing and sometimes praying, it became clear that she had been ‘more or less unhinged’ since the birth believing that people accused her of murdering the child who had died a week or so later.[29]

Mild depression had long been recognised as a more or less normal outcome of confinement – Queen Victoria was ‘troubled with lowness’ after the birth of each of her nine children – but more florid conditions such as the ones described above fell under the diagnostic umbrella of puerperal insanity. The term came to be used during the 19th century to describe a wide range of conditions but it is possible that, rather than representing a distinct postnatal illness, the insanity described in the asylum records may simply reflect the daily hardships endured by pauper women like Mary and Elizabeth which were exacerbated during pregnancy. In some cases childbirth may have triggered an illness that was waiting to happen.

Continuing ‘confinement’

Ellen Eliza Griffith’s postpartum insanity could not be attributed to poverty however. Married to a prosperous farmer in Llanfaes, near Beaumaris, she was admitted to Denbigh as a private patient in 1890 with an attack of mania which may have been, if not induced, then at least aggravated by being confined to her bedroom after the birth of her first child.

Stands up in bed and feels along the bedroom wall saying she sees insects creeping on the wall, when there are no such things to be seen.

Says she sees red and black colours, which develop into hideous forms representing something which she fails to describe in a way to be understood. …Jumps out of bed and threatens violence to those nursing her.[30]

There are striking similarities between Eliza’s experience and the account of an unnamed mother in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s closely autobiographical book which describes the descent into madness of a young woman locked into a top floor room to ‘rest’ after the birth of her child had left her mildly depressed. The mother is disturbed by the ‘smouldering unclean yellow wallpaper’ in the room:

There are things in that paper that nobody knows but me, or ever will.

Behind that outside pattern the dim shapes get clearer every day. It is always the same shape, only very numerous. And it is like a woman stooping down and creeping about behind that pattern.

The outside pattern is a florid arabesque, reminding one of a fungus. If you can imagine a toadstool in joints, an interminable string of toadstools, budding and sprouting in endless convolutions… All those strangled heads and bulbous eyes and waddling fungus growths just shriek with derision! [31]

It was common practice, as an extension of their ‘lying-in’, to confine newly delivered mothers to a bedroom away from the rest of their family where their frantic efforts to escape, often by jumping through a window, would provide the rationale for an asylum admission. Ellen Davies, an unmarried farm servant born with a ‘double hare lip’ was admitted to Denbigh after beating her sister and trying to jump through a window with the intention of getting to Cader Idris – a mountain she would have been able to see from her home in Dolgelley.[32] The daughter of ‘respectable people’ in Llanllyfni, Margaret Jones had torn all her bedding and thrown food at her parents before trying to jump through her bedroom window.[33]

The current view that postpartum psychosis is best regarded as an ordinary psychosis triggered by childbirth rather than a distinct phenomenon has been questioned by Tschinkel et al who found that of the 101 first admissions to Denbigh asylum between 1875 and 1924 with puerperal insanity, 38 women displayed clinical features which could not be precisely matched to any other ICD10 classification.[34] This study also found that far fewer women are now admitted to hospital with the same symptom profile and this has resulted in the closure of a specialized post partum unit, the Heidi Humphreys Unit, which was opened at Ysbyty Gwynedd in 1995.

The delights of chloroform!

Whether or not postpartum psychosis can be established as a disorder distinct from other disorders, it has always been linked to suicide. Suicidal intentions were common amongst patients admitted to Denbigh Asylum after childbirth and two women from North West Wales were dead within a week of their discharge.

In October 1905 Mary Ellen Doughan (6649), a labourer’s wife from Bethesda, was admitted after giving birth to her second child. The labour had been natural and Mary Ellen’s reception order suggests that she had been ‘helped’ with chloroform although this had not quite provided the ‘delightful’ experience that James Young Simpson described in 1847 after first using chloroform in his obstetric practice:

I have employed it also in obstetric practice, with entire success. The lady to whom it was first exhibited during parturition had been previously delivered in the country by a perforation of the head of the infant, after a labour of three days’ duration. In this, her second confinement, pains supervened a fortnight before the full time. Three hours and a half after they commenced, ere the dilatation of the os uteri was completed, I placed her under the influence of the chloroform, by moistening, with half a teaspoonful of the liquid, a pocket-handkerchief, rolled up in a funnel shape, and with the broad or open end of the funnel placed over her mouth and nostrils. In consequence of the evaporation of the fluid, it was once more renewed in about ten or twelve minutes. The child was expelled in about twenty-five minutes after the inhalation was begun. The mother subsequently remained longer soporose than commonly happens after ether. The squalling of the child did not, as usual, rouse her; and some minutes elapsed after the placenta was expelled, and after the child was removed by the nurse into another room, before the patient awoke. She then turned round, and observed to me that she had “enjoyed a very comfortable sleep, and, indeed, required it, as she was so tired,[3] but would now be more able for the work before her.” I evaded entering into conversation with her, believing, as I have already stated, that the most complete possible quietude forms one of the principal secrets for the successful employment of either ether or chloroform. In a little time, she again remarked, that she was afraid her “sleep had stopped the pains.” Shortly afterwards, her infant was brought in by the nurse from the adjoining room, and it was a matter of no small difficulty to convince the astonished mother that the labour was entirely over, and that the child presented to her was really her “own living baby”.

Perhaps I may be excused from adding, that since publishing on the subject of ether inhalation in midwifery, seven or eight months ago,[4] and then for the first time directing the attention of the profession to its great use and importance in natural and morbid parturition, I have employed it, with few and rare exceptions, in every case of labour that I have attended, and with the most delightful results. And I have no doubt whatever, that some years hence the practice will be general. Obstetricians may oppose it, but I believe our patients themselves will force the use of it upon the profession.[5] I have never had the pleasure of watching over a series of better and more rapid recoveries, nor once witnessed any disagreeable result follow to either mother or child, whilst I have now seen an immense amount of maternal pain and agony saved by its employment. And I most conscientiously believe, that the proud mission of the physician is distinctly twofold — namely, to alleviate human suffering, as well as preserve human life.[35]

Ten days after the birth of her child Mary Ellen, deluded that she was being chloroformed and that her clothes and food were full of chloroform, was proving quite uncontrollable and ’dangerous to herself and others’. She had threatened to stab her husband and there were fears she would harm her baby. A good looking woman, ‘nicely spoken and well behaved’, she was expected to make a quick recovery and within four months she was discharged ‘in the best of spirits’ to the care of her husband.

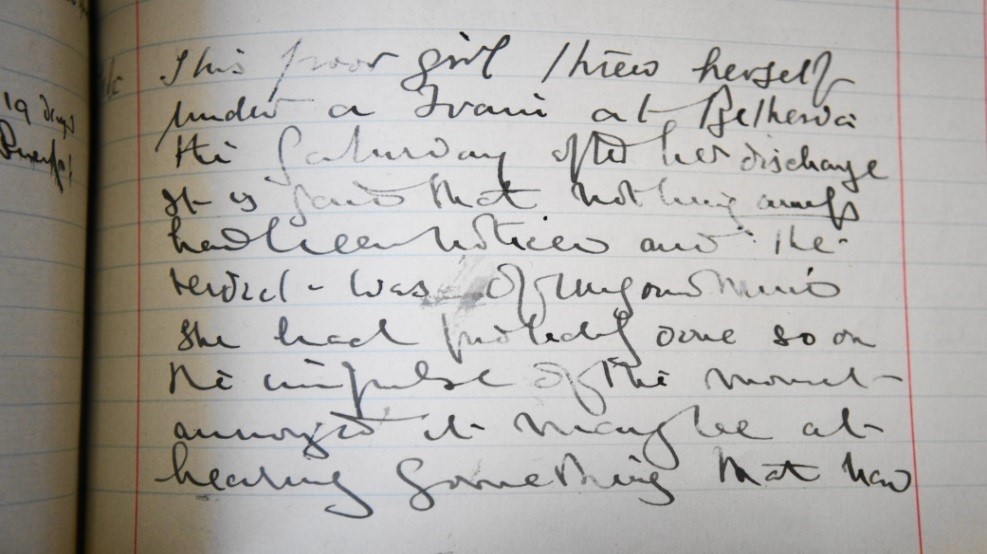

Mary Ellen threw herself under a train at Bethesda the Saturday after her discharge.[36]

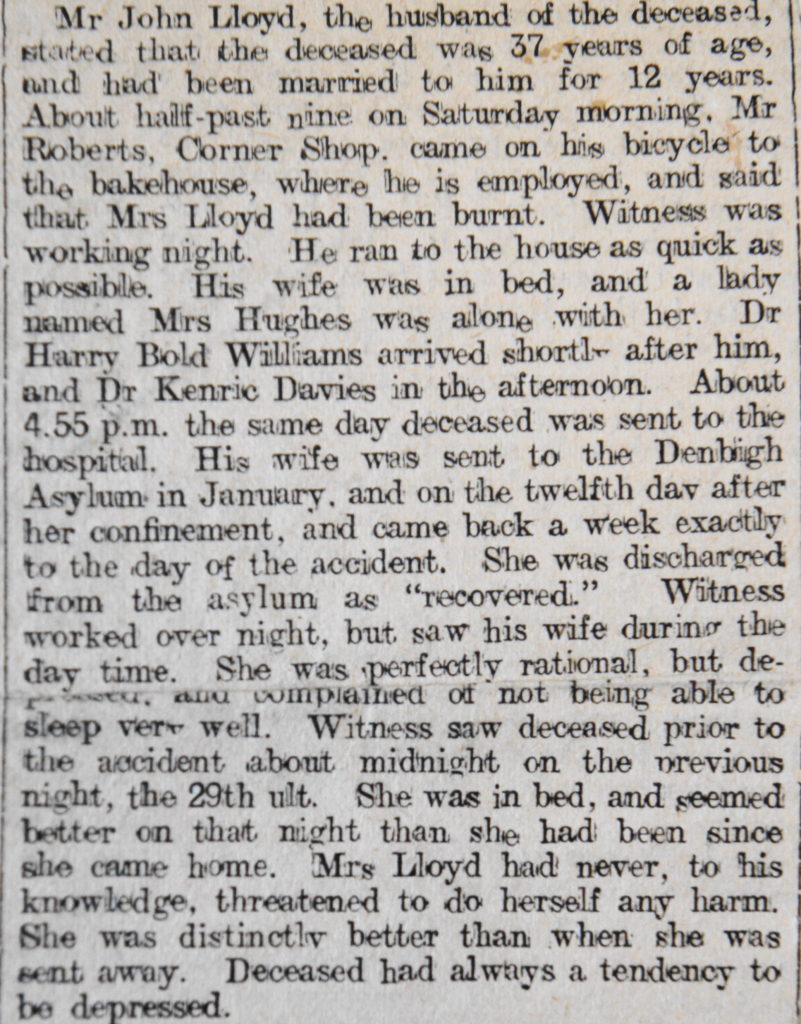

The circumstances of Mary Ellen Doughan’s death on the railway line conclusively indicated suicide but the death of Mary Lloyd, outlined below, was not quite so clear cut and the subsequent inquest returned a verdict of accidental death.

‘Sad Burning Fatality at Llandudno – A Melancholy Case’

A newspaper cutting carrying this headline is pasted into the 1903 case book and the following extract from the report suggests that Mary’s state of mind remained fragile despite her recent discharge from the asylum. [37]

Mary Lloyd, a Llandudno baker’s wife, had been admitted to Denbigh shortly after the birth of her sixth child in January 1903 after attempting to get out of her bedroom window, claiming to be ‘the Virgin Mary come to life again to prevent women having children’. Mary made a steady improvement and was discharged ‘recovered’ after six months. Just a week later her 9 year old daughter May found her mother in flames, ‘her flannelette nightdress having caught alight from a candle which had fallen to the floor’.

Although the inquest returned a verdict of accidental death the newspaper report goes on to suggest another grim possibility:

A neighbour found Mrs Lloyd ‘in a terrible state, and her clothes burnt to dust’. The witness expressed the opinion that Mrs Lloyd was very depressed at times and did not seem any better on her discharge from the asylum. In her opinion “it was a mistake to relieve her from the asylum as they did.

‘Unfit’ to multiply

When he took up his post as assistant superintendent in charge of the women’s section in 1883 Dr Herbert noted the cases of insanity attributed to pregnancy and childbirth. Many years later as chairman of the Denbighshire County Council’s ‘Committee for the Care of Mental Defectives’ he drew upon this experience to support the view that the multiplication of the ‘unfit’, a group which included the recovered insane, should be limited through sterilization.[38]

Vast numbers of wives suffered insanity due to pregnancy. Most of them would recover, but they would return again and again and the children they bore would themselves create further children in their own mental image…

Already we are a C3 nation, what we shall be in fifty years time I dare not contemplate.[39]

Dr Herbert’s eugenic concerns, shocking to read of now but not unusual in the 1930s, were not shared by the National Birth Control Association, which was campaigning for contraception rather than sterilization, nor by colleagues within the county council. The management committee at Denbigh, after lengthy consideration, also rejected his proposals for sterilisation. Dr Herbert subsequently turned his attention to birth control and, in a report which linked poverty with eugenic undesirability, he included amongst the categories of married women eligible for contraceptive advice ‘the wives of the very poor’. Women on discharge from mental hospitals, women suffering serious disease and those with a history of difficult labours were also listed in his report and in 1931 the County Council agreed that ‘women in poor circumstances who are, in consequence of too frequent pregnancies, falling into ill health’ should be provided with advice. Dr Herbert’s work in the asylum and his interest in the biological aspects underlying mental pathology could therefore be said to have paved the way for the establishment of birth control clinics in North Wales.

Depression and a widening gender gap

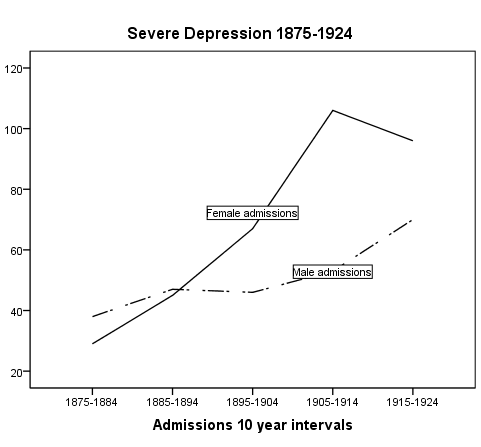

Admissions to Denbigh had been increasing steadily since 1890 and, while Dr Cox reported in 1905 that ‘male admissions continue to prevail’, almost as many women as men were admitted from North West Wales during the year. More significantly, a close inspection of retrospective diagnoses reveals a changing dynamic.

1905 Asylum Admission: Current diagnoses

| Diagnosis | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Dementias | 1 | 5 |

| Organic disorders | 10 | 6 |

| Alcohol related disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Schizophrenia | 13 | 13 |

| Delusional disorder | 1 | 2 |

| Acute and transient psychosis | 11 | 7 |

| Unspecified non-organic psychosis | 2 | 3 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 8 | 7 |

| Depressive episode | 7 | 9 |

| Post partum disorder | 0 | 4 |

| Neurotic disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Personality disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Mental handicap | 0 | 0 |

| Epilepsy | 4 | 1 |

| General paralysis of the insane | 1 | 0 |

| Insufficient data (no case notes) | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 58 | 57 |

While the records from 1875 to 1890 show more men than women being diagnosed with a severe depressive episode, after 1890 there was a sharp rise in female admissions with this diagnosis and this was a trend which became more pronounced after 1905 and continues [40] That the picture began to change 40 years before depressed patients could present voluntarily for care works against the commonly used explanation that women are simply more likely to report their symptoms and reasons for the change must remain uncertain.

In 1905 seven men and nine women were admitted from North West Wales severely depressed and a third of these patients had attempted suicide. A revised system of issuing special ‘Caution Cards’ for suicidal patients had been operating since the 1890s when the inadequacy of existing arrangements for supervision were clearly exposed and it was this group of depressed patients who most needed constant observation.

Ellen Jones of Tremadoc (6960) who believed her blushing to be responsible for the onset of melancholia – ‘she thinks it is noticed by others who place their own construction on it’ – was put on a Special Caution Card in 1905 after Dr Herbert had seen her running away ‘over the rails’ in an attempt to get to the station and ‘put herself under a train’. Cards were also issued for Catherine Jones, a single woman whose insanity was attributed to the loss of a servant ‘to whom she was attached’ (6559) and for Maggie Williams a young domestic servant from Portmadoc who had tried to drink paraffin after the failure of a love affair (6579). With careful nursing and vigilance, these women all recovered in a relatively short time.

However, no system is fool proof and a year later, just two days after being admitted to Denbigh, a Pwllheli housewife used her stockings to hang herself from her bedstead. Ann Hughes, a private patient with a ‘pleasant and taking personality’ had not been thought actively suicidal and no caution card issued although she had been put in the constant care of a nurse and ‘eats with spoon etc.’[41] Her case notes describe events:

I was called hurriedly about 9.35 (pm) and, on arriving in her room a minute afterwards, found her suspended to the rail at the head of her bed by a pair of long black stocks firmly knotted together at each end. Her whole weight, some 13 stone, or nearly so, was suspended and she was evidently quite dead.

In a subsequent newspaper article ‘SUICIDE AT THE ASYLUM – THE INQUEST’ it was reported that Dr Cox laid blame for the suicide firmly on the attendant who, when Ann Hughes had complained of cold feet, had allowed her to keep her stockings.

The nurse should not have undertaken to allow the patient to have stockings or the other garment, a dressing gown, without having a particular consent of a medical superior. She should, in fact, have made a special request….I consider that she was wanting in forethought and consideration…She yielded, no doubt, to the appeals of the patient, but I consider that she was not adopting a distinct rule which is well known and in vogue here.

The inquest jury disagreed and found that the patient had received ‘all due care’ but suggested that her bedstead was not suitable for use by someone with any suicidal tendency.[42]

Dr Cox’s annoyance may have been especially marked by the fact that this suicide had broken a long record on the female side. In his annual report the medical superintendent noted that 30 years had elapsed since the last female suicide at the asylum. Perhaps this was a genuine error or maybe he was ‘massaging statistics’ by maintaining the view that Emily Clara Murphy’s drowning just 20 years earlier had been an unfortunate accident. On a visit to Rhyl with her attendant, Emily had quite suddenly jumped over the side of the pier and drowned. She had been looking forward to her day out and, although the incident is reported as suicide in the 1895 annual report, Dr Herbert suggests in Emily’s clinical notes that her action may have been:

…the result of a sudden impulse and it may be without any definite wish to destroy life, perhaps induced by the sight of the cool green water underneath the Pier.[43]

Another discharged patient drowned in 1895, this time in the Menai Straits, but Dr Cox had no such doubts about Jane Jones’ intentions. Becoming melancholic after the death of her invalid mother and the loss of some money she had invested in a ship she went to live in Menai Bridge with her sister who found her trying to strangle herself and threatening to plunge herself into the Straits. After spending three months in the asylum she was removed by her relatives against the advice of Dr Herbert who ‘explained to them personally her condition and warned them strongly as to the possibility of suicidal tendencies becoming suddenly and unexpectedly developed.’ A few weeks later, after her relatives had gone out, Jane left the house, locked the door behind her and threw herself into the Straits. Her body was noticed floating by some visitors and recovered a short time later.

The North Wales Chronicle carried a short paragraph about the inquest in which Jane, described in her case notes as ‘Supervisor Servant in a good family’, was identified as former housekeeper to local philanthropist Mr Richard Reynolds Rathbone of Glan Menai.[44] The Rathbones, a Liverpool family of non-conformist merchants and ship-owners, had strong links to North Wales and after marrying Frances Susannah Roberts, an Anglesey gentlewoman, in 1859 Richard Reynolds Rathbone spent much of his time at the family home in Llandegfan. Could Jane’s lost money have been invested in a Rathbone ship?

Despite measures taken to prevent patient suicides – removal of shoelaces, neckties, scarves and cutlery, the dispersal of groups thought to be sharing suicidal ideas and constant supervision of those ‘under card’ – attempts were still made using whatever means were available. Nooses were made from sheets and scraps of strong tick clothing and one woman tried to strangle herself with her long hair. But only four in-patients from North West Wales were successful. Suicides were always entered into the deaths register and noted in annual reports while inquests on the four patients who killed themselves after being discharged were reported at length in the local newspapers and cuttings pasted into the case book. Such detailed record keeping, above and beyond what the regulations stipulated, allows for some degree of confidence in establishing a suicide rate for asylum patients – which seems to compare very favourably with the suicide rate for psychiatric patients today (see Healy et al Mortality in Schizophrenia and Psychosis).

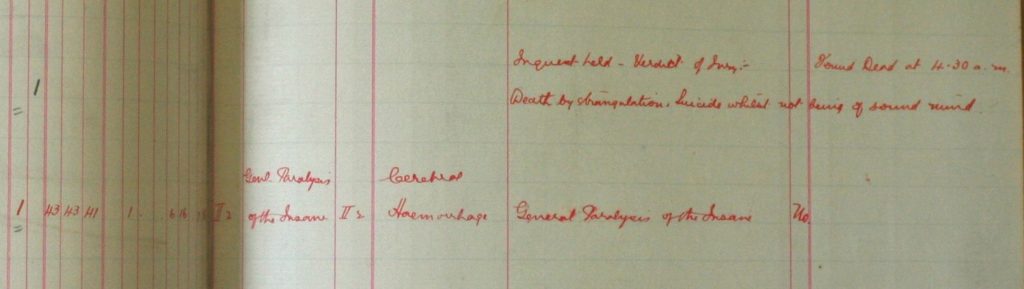

Extract from Death Register recording a female suicide ‘death by strangulation’.

Workhouse v asylum

Reception orders and case notes generally suggest that a suicide attempt would guarantee admission to the asylum and this is made explicit in the case notes for 16 year old Owen Pritchard, who was brought from Conway Workhouse after attempting to hang himself with his neckcloth:

States that he was ill used in Workhouse and that he attempted to commit suicide in order that he might be brought here, a workhouse inmate having told him that.[45]

Owen was soon looking ‘all the better for his stay here’ and subsequent attempts to harm himself were not taken seriously but dismissed as being intended simply to alarm. And probably to make certain that he wasn’t sent back to the workhouse!

Asylum doctors wanted asylum beds to be occupied only by those patients who could not safely be managed in a workhouse hospital. It was thought that, given enough attention, elderly demented paupers or young idiots could be adequately cared for in the workhouse. Dr Herbert did not think Mary Griffith (6589) – quiet and perfectly manageable – needed to be held in the asylum. Despite her many delusions she ‘ought to do in the Workhouse’. And Dr Cox’s response had been scathing when Richard Pritchard, aged 16 and weighing just 48 lbs was brought from the Carnarvon workhouse because he was ‘becoming too strong for the Workhouse accommodation’:

His noisy and dirty habits proving too much for the delicate and refined susceptibilities of the Workhouse Master he has suddenly developed a strength…which his general appearance certainly belies.[46]

However, despite being more than happy to discharge less troublesome patients to the workhouse Dr Herbert was harshly critical of the care they were likely to receive there. When Margaret Jones, an old lady with a long history of psychosis, was readmitted to the asylum from the Bangor and Beaumaris workhouse he referred to her as:

A striking example of the superiority of Asylum to Workhouse life. On leaving here she was a big, well nourished and healthy old woman. Now she is feeble and decrepit and shrunken to half her former size…Moreover her habits have become dirty and her appetite feeble.[47]

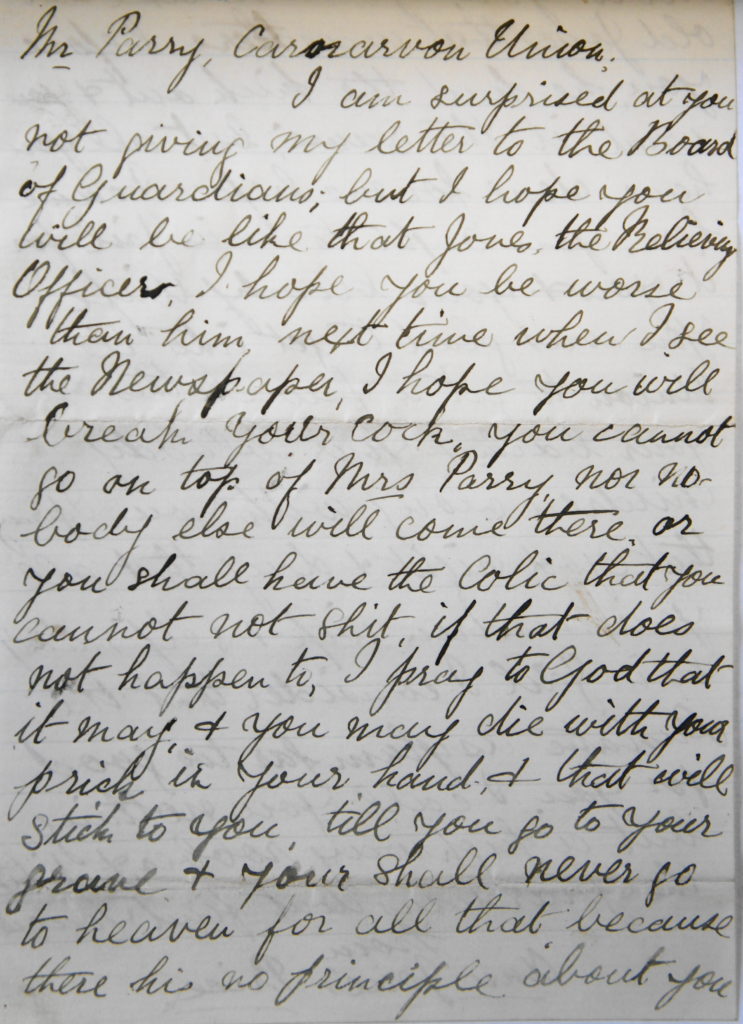

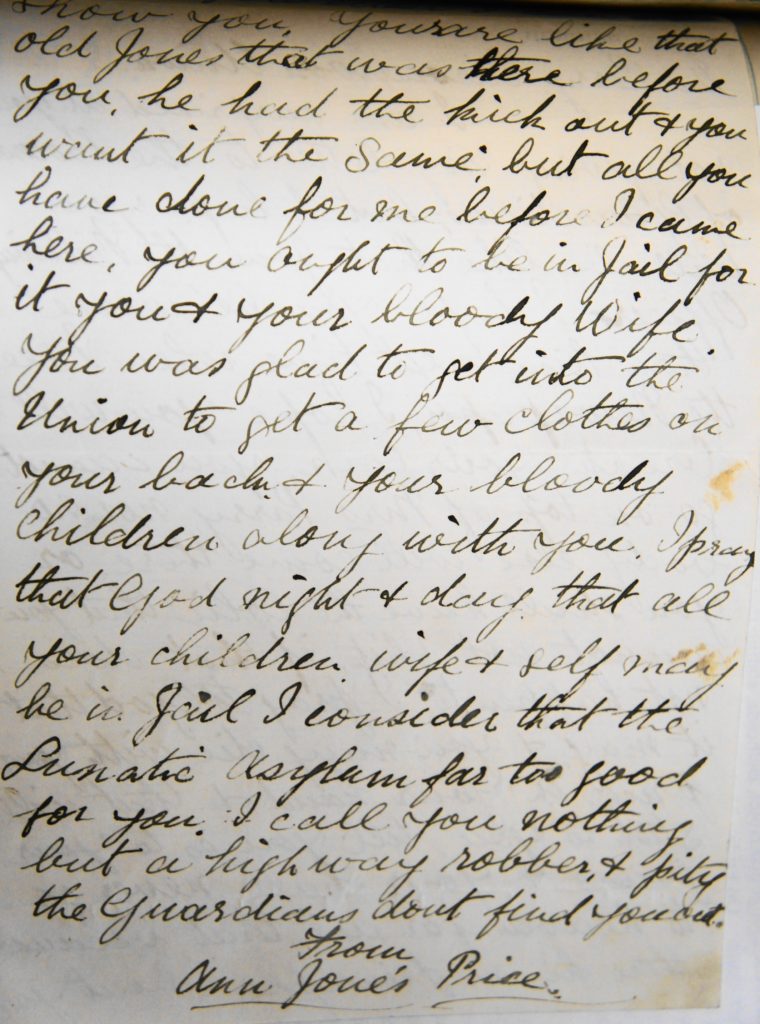

Ann Price Jones made clear her own feelings about the Carnarvon workhouse – and more particularly about John Parry the master – in a letter pasted into her case notes.[48]

(…nor in them that carries the same trade as you either. I can…)

It may have been hard for Dr Herbert to interpret Ann’s letter as a legitimate complaint and he dismissed it as one of the ‘rambling accusations against the Workhouse authorities of ill treatment etc. etc. which have no truth in them’. Yet the anger which prompted Ann’s violent and destructive behaviour in the asylum may have had some foundation in her ill-treatment by Mr Parry and his predecessor. While Dr Herbert accepted that her stepfather had ‘purposely ill-treated her with the object of obtaining her money’ and in this way contributed to her transformation from steady hardworking servant girl aged 18 to drunken prostitute aged 23 he failed to endorse her allegations of mistreatment at the workhouse.

However, in April 1905 a few weeks after Ann Price Jones had been boarded out ‘relieved’ to Carmarthen Asylum, Margaret Owen (6565), a 68 year old widow, was admitted to Denbigh from Carnarvon Workhouse complaining that she had been:

…tormented by the Workhouse Porter (at Carnarvon) who has tried to kill her and calls her all the filthy things he can. She hears him doing so here and she imagines he has followed her. He also incites others to abuse her.

Margaret was suffering from senile dementia but her ideas about the porter may have had some validity because Ann Williams (6566) admitted to the asylum a few weeks later with melancholia also complained of being unkindly treated at Carnarvon workhouse and ‘she also detests the Porter’. William Thomas (6508) arrived at Denbigh with the marks of restraining anklets on his ankles and a wound on his forehead having been straight jacketed at the same workhouse.

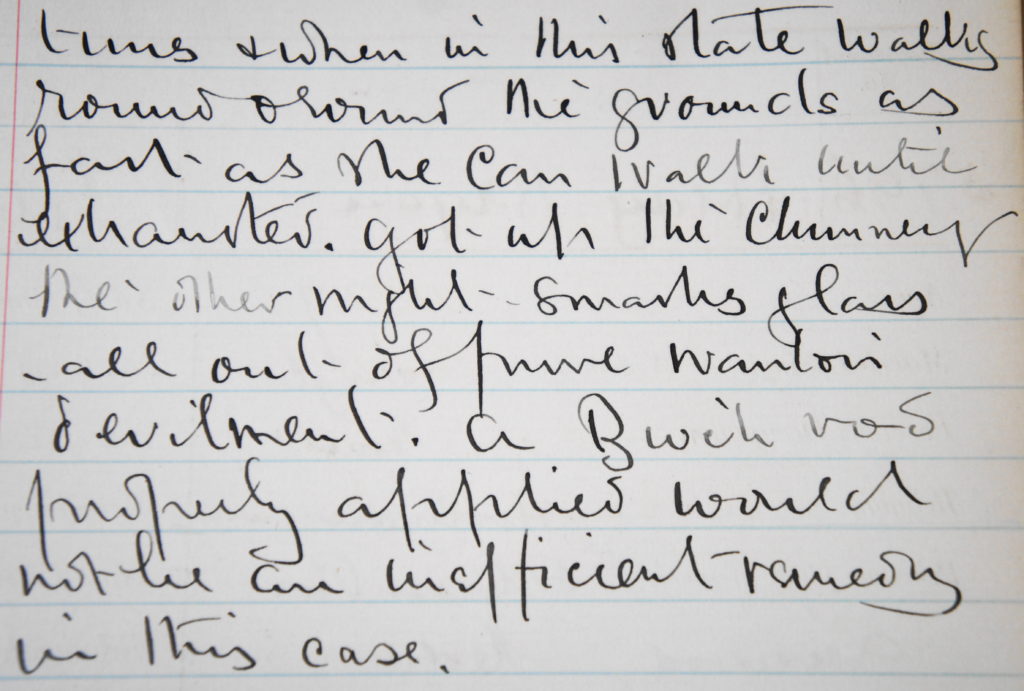

Ann Price Jones terrorised her attendants, smashed windows and made regular attempts to harm herself but she also proved a useful nurse ‘feeding and dressing patients and doing ward cleaning’. Dr Herbert, describing her during one of her quieter spells as a slumbering volcano whose difficult behaviour might best be remedied by a birching!

Ann was one of very few asylum patients (1 per cent) to be diagnosed by modern psychiatrists with a personality disorder. Ten to fifteen times this number of patients were admitted to the North West Wales DGH Psychiatric Unit in 1996 with a diagnosis of personality disorder and, when other patients who had a personality element to their mental illness, such as those with alcohol or drug related disorders were included the difference was even greater.[49] (see Healy et al 2001 Psych bed Utilization).

Alcohol was certainly a factor in Ann’s insanity – she had regularly been held in Carnarvon Gaol for being drunk and disorderly – but her case notes hint that she may also have developed ‘morphinomania’ as a result of her treatment at the asylum. She was treated for the symptoms of gastric ulcer in 1887 (although later case notes attribute her stomach problems to her having swallowed nails!) when her pain was ‘best relieved by Morphia hypodermically’ and until 1895 she was given injections at least daily when the pain was severe. When readmitted in 1901 her condition was described as ‘not unlike as if she were under the partial influence of an hypnotic’ and she ‘liked an opiate at night’ during her final admission to Denbigh where she died of liver disease in 1912.

Morphine based laudanum was readily available and affordable to buy over the counter in chemists and grocers shops and was extensively used by the poorer classes. Morphine was also the principal ingredient of patent medicines like J. Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne, along with lesser amounts of chloral and tincture of cannabis indica. Advertised as a cure for most common ailments from coughs to dysentery versions of the chlorodyne mixture were made by every chemist and sold without restriction during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Ann would not have found it impossible to maintain a habit.

Whiffs of change?

It is to be hoped that Dr Herbert’s reference to the application of a birch rod in Ann’s case was whimsical. Yet by the beginning of the 20th century asylum doctors had cause to feel frustrated that they still had no effective remedies for insanity at their disposal and were using treatments that differed little from those they had used in 1875. Heredity and family weakness were generally used to explain the failure to find a cure.

Although the range of diagnoses in 1905 generally remained limited to the various forms of mania, melancholia and dementia new classifications for disease would soon appear in the Denbigh case notes. Bessie Hughes, a 17 year old domestic servant, admitted in October 1905 suffering from ‘Depression with Stupor’ (6644) was described just a few months later as ‘a good example of Dementia Praecox’. This rediagnosis predates a national conference on the classification of insanity at which a new disorder of primary dementia (effectively an English translation of dementia praecox) was proposed. In fact Bessie was discharged cured after 9 months in hospital and was never readmitted but her diagnosis of dementia praecox in early 1906 illustrates how ready the medical staff at Denbigh were to receive Emil Kraepelin’s ideas. Often referred to as the founder of modern psychiatry, Kraepelin advocated disease course as a classificatory principle for mental disorders and dementia praecox, later schizophrenia, was characterised by progressive dementia (to read more see Healy et al 2008 – ‘Historical Overview: Kraeplin’s impact in psychiatry‘).

In this context, it may be significant that from 1905 patients were less likely to be classified on admission and their diagnosis would change over the duration of their stay. For example John Robert Griffith, a 20 year old bank clerk, was admitted without a diagnosis in 1907 but thought to be suffering from mania when he was examined a week or so later. Three years later he is referred to as ‘A chronic Dementia Praecox case. No volitional power. Walks about aimlessly and often laughs and makes grimaces without cause.’ [50]

While new medical treatments for insanity remained elusive, from 1905 psychological treatments were attracting interest. Brought to the UK by Ernest Jones, a Welsh neurologist who had read of Freud’s work in a German psychiatric journal, these treatments would be given impetus by the numerous psychological casualties of World War 1 – mostly young, fit men with no history of madness in their families.

The major social and economic changes taking place in North West Wales in the early part of the 20thcentury, including the great religious revival which ultimately made way for a more secular society and the irreversible decline of an industry which had been a foundation of the region’s economy for almost a century, are clearly reflected in the records from Denbigh asylum. But changes in the wider society can also be identified from the case notes.

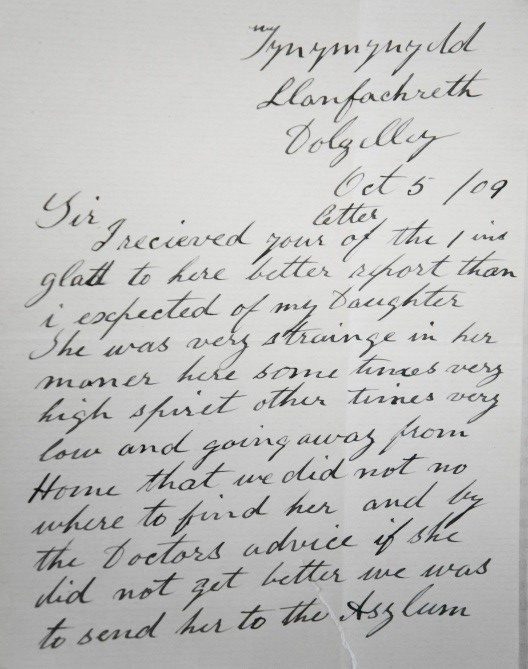

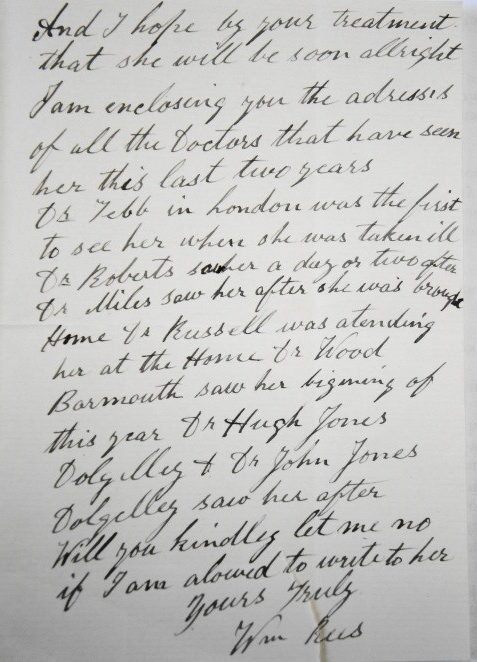

Dr Herbert’s assessment of Margaret Rees, a 25 year old domestic servant, as ‘easy and refined in her conversation and very intelligent and well informed’ did not prevent him from noting that she ‘talks a little foolishly upon ‘The New Religion’, ‘Women’s Rights’ etc.’’[51] Letters from Margaret’s father and her Dolgelley doctor are pasted into the case book and suggest her troubles began in London where she was presumably in service and where an intelligent young woman would have been well aware of the various working women’s movements being formed at the time. Margaret may even have been amongst the 250,000 people who gathered in Hyde Park in support of women’s suffrage.[52]

A domestic servant with the degree of education this young woman’s notes suggest may have been an exception because, although by the turn of the century the majority of people in England and Wales were literate to the extent that they could sign their own names, access to anything more than the most rudimentary education was limited. The aim of the 1902 Education Act was to enable children to build on basic skills by establishing grant aided secondary schools but these schools could charge fees for most of their places.

This may explain why, in 1905, Robert Lewis’s melancholia was attributed to worry about providing ‘an expensive education’ for several of his children (6661). A quarry brakesman at Blaenau Ffestiniog, it seems Robert was struggling to put his own children among the fewer than 10 per cent of children who would receive a secondary education. However, it turned out that this was not the struggle which brought him to the asylum – it soon emerged he was suffering from pneumonia and he died, still delirious, after just 9 days in hospital.

These were small changes and much greater social, economic and cultural upheaval lay years ahead. But as 1905 at Denbigh ended with the usual Christmas dance and a dinner prepared by a newly-appointed ‘man-cook’ and his team of male patients, there was more than a whiff of roast turkey in the air!

Read more ‘1920‘.

Footnotes

[1] 57th Annual Report, Minutes of a conference on the subject of future accommodation for patients held September 1905.

[2] 56th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report 1904.

[3] 56th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report 1904

* ‘Lime-light’ or ‘calcium-light’ was a type of stage lighting in widespread use in theatres by the 1870s. Created by directing an oxyhydrogen flame at a cylinder of quicklime, it was used to highlight solo performers.

[4] DRO/HD/1/372/Case no. 6079

[5] 50th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report 1898-1899

[6] 56th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report 1904

[7] Office of National Statistics

[8] Gwynedd Record Office, Report from Penrhyn Quarry Hospital, Bethesda, January 1922.

[9] Llangefni Record Office WG/3/922

[10] DRO/HD/1/Case no. 5654

[11] 57th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report

[12] 56th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report

[13] 57th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report

[14] Gwynedd Record Office, Extract from a petition sent by employees at Penhyn Quarry who had returned to work asking for protection against the strikers, from a report on the Bethesda Riots Standing Joint Police Committee in 1902.

[15] DRO/HD/1/372/Case nos. 5833 and 6039

[16] DRO/HD/1/372/Case no. 6026

[17] R. Merfyn Jones, The North Wales Quarrymen 1974-1922, University of Wales Press (1982)

[18] 57th Annual Report, Medical Superintendent’s Report 1905

[19] AR 1905 Medical Superintendent’s Report

[20] R Tudor Jones, Geraint Tudor (ed.) Tan ar yr Ynys: Diwygiad 1904-05 ar Ynys Mon, Gwasg Gwynedd (2004)

[21] North Wales Chronicle Jan 7th 1905

[22] North Wales Chronicle Jan 7th 1905.

[23] Kevin Adams, A Diary of Revival: The Outbreak of the 1904 Welsh Awakening, CWR (2004).

[24] DRO/HD/ 1/375/Case no. 6460

[25] DRO/HD/1/356/Case no. 10478

[26] DRO/HD/1/331/Case no. 2585

[27] DRO/HD/1/356/Case no. 9636

[28] DRO/HD/1/339/Case no. 4616

[29] DRO/HD/1/335/Case no. 3711

[30] DRO/HD/1/337/Case no. 501

[31] The Yellow Wallpaper, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1892, reprinted by Virago Press 1981, pp 16-30.

[32] DRO/HD/1/331/Case no. 2674

[33] DRO/HD/1/339/Case no. 4663

[34] Tschinkel, S, Harris, M, Le Noury, J, Healy, D (2007) Postpartum psychosis: two cohorts compared, 1875-1924 and 1994-2005, Psychological Medicine, 37, 529-536.

[35] James Young Simpson, ‘On a New Anaesthetic Agent, More Efficient than Sulphuric Ether’, Lancet, November 21st 1847, 549-550.

[36] Entered into the case book as an addendum to Mary Doughan’s clinical notes.

[37] DRO/HD/1/344/Case no. 6121

[38] Julie Grier (1998), Eugenics and Birth Control: Contraceptive Provision in North Wales 1918-1939, Social History of Medicine.

[39] Quoted in Grier, CMAC, SA/FPA/A11/61A, Dr Herbert, pamphlet ‘Family Limitations’.

[40] It remains the case that women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with severe depression. Of 203 patients admitted to the Hergest Unit between 1995 and 2005, 57 per cent were women (Harris et al, 2011. The incidence and prevalence of admissions for melancholia in two cohort (1875-1924 & 1995-2005). Journal of Affective Disorders, 134 (1-3): 45-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.015).

[41] DRO/HD/1/346/Case no. 721

[42] North Wales Chronicle 18th August 1906

[43] DRO/HD/1/334/Case no. 451

[44] North Wales Chronicle, July 27th, 1895.

[45] DRO/HD/1/363/Case no. 3677

[46] DRO/HD/1/366/Case no. 4297

[47] DRO/HD/1/337/Case no. 4203

[48] DRO/HD/343/Case no. 5793

[49] Healy et al.(2001), Psychiatric bed utilization: 1896 and 1996 compared, Psychological Medicine, 31, 779-790.

[50] DRO/HD/1/375/Case no. 734

[51] DRO/HD/1/348/7337

[52] Greater London Authority (2002)