Pam Michael (1997), Quarrymen and Insanity in North Wales, Industrial Gwynedd Vol. 2, pp 34-43.

In 1888 a 44 year old quarryman and father of three, D.W from Glandwr, Blaenau Ffestiniog, was admitted to the North Wales Lunatic Asylum. Six months prior to his committal he had met with an accident to his foot whilst working at the Quarry. He was treated for his injury at the Oakley Hospital, and over a period of five months made a good recovery. However, soon after discharge his mind became affected. According to the asylum case notes, he appears to have:

“been labouring under the idea that his long residence in hospital would incapacitate him from further employment”.[1] “About a month ago”, the doctor’s summary of the case continues, “he became low and desponding and on going to his work would not take care of himself viz. the blasting and so on of the rocks. Has latterly become worse, refusing to take his food and restless and sleepless day and night.”

D.W. was described as a steady, temperate and industrious man, and no doubt the experience of being discharged from hospital to almost immediately resume his responsibilities as breadwinner and return to the quarries must have proved unsettling, if not traumatic. The medical certificate signed by the local doctor stated that D.W. “Labours under delusions that he will get no work anymore in the quarries, and that he must leave the place. He also sees the managers in different places in the House. He is constantly untying his boot laces – even at it for hours at a time.” A neighbour further certified, before a magistrate, that D.W. had “on more than one occasion taken a knife in his hand and threatened his own wife”. This quarryman was finally discharged in 1913, having been a patient at the asylum for 25 years.

The description of this man’s illness, and the conjunction of his physical injury and subsequent ‘mental instability’, his anxieties about his ability to carry out his work, his carelessness in the face of occupational dangers, the intrusion of his fears concerning his job into the privacy of his home, and finally his turning violently toward his wife – these ‘symptoms’ of illness, derived from his medical case notes, show how intimately bound up with the concerns of everyday life are the clinical and medical conditions of the insane. Madness presents as primarily a social illness,[2] so much so that some writers have even gone so far as to assert that there is no such thing as mental illness – only “problems of everyday living”.[3]

The case-records of the North Wales Lunatic Asylum, opened in 1848, provide a window on the everyday concerns, anxieties, and behaviour of a broad spectrum of working people from the mid-19th century through to recent times. Partly a subscription hospital, (with contributions towards its building from local gentry, quarry owners, and quarry workers) but primarily a public asylum financed and supported by the five counties of North Wales, Anglesey, Carnarvonshire, Flintshire, Denbighshire and Merionethshire, it served the whole of North Wales, until its closure in 1995.

The run-down of the hospital posed the question of what would become of this rich medical and historical resource. A number of substantial deposits of material had been transferred to the local archive, but a considerable range of material remained in the hospital. In 1993 the School of History and Welsh History of the University of Wales Bangor, received a grant from the Wellcome Trust to support an in-depth study of the papers, and to research the history of mental illness and society in North Wales. This article is based on a small section of that research, but serves to illustrate the case for having the material both preserved and analysed.

Many writers have emphasised the arduous physical conditions faced by the quarrymen, their exposure to extremes of cold and wet, the effects on their health, the frequency with which they experienced rheumatism and arthritis, the high risk from accidents, and the common incidence of chest complaints, and tuberculosis.[4] Quarriers, rockmen and miners had an average expected age of only 48 years.[5] R. Merfyn Jones writes of the quarryman carrying, during his life “. . the involuntary badges of his identity, in particular, his ill-health”. [6]

Whilst there is nothing to suggest that quarrymen were more prone to suffer from mental illness than any other group of workers in North Wales in the 19th century, nonetheless, when their case histories are analysed in detail, they do constitute a distinct group amongst the patients at the Asylum. The details of their committal, and the background information noted down by the medical officer at the Asylum, provide a rare insight into what otherwise has remained a hidden side of the work, and personal and community life of the quarrymen.

The Wellcome Trust funded research project, with support from Clwyd Health Authority, took a 10% sample of all patients admitted to the hospital from its opening in 1848, through to the outbreak of the Second World War. During the period 1875 to 1914 around 10-12% of the males in this sample were quarrymen. They are probably not over-represented as a group, since this proportion seems to do no more than reflect their importance in the labour force of North Wales.[7] A number of government enquiries were carried out which reported not only on the working conditions in the quarries,[8] but also on the physical health of the quarrymen, and the Denbigh records augment these other sources in valuable ways.

Few people have written openly, or at length, about mental illness in Wales. The novel of Caradog Prichard, Un Nos Ola Leuad (Full Moon),[9] is quite exceptional in dealing directly with the experience of insanity. Having worked closely with the asylum records for some years now, I still regard this novel as a very honest portrayal of the intensely personal torment of witnessing a mental breakdown, beautifully evoked through the eyes of a child growing up in a quarrying community. It offers a sensitive literary insight into the harsh experiences which often accompanied a woman’s slide into insanity.

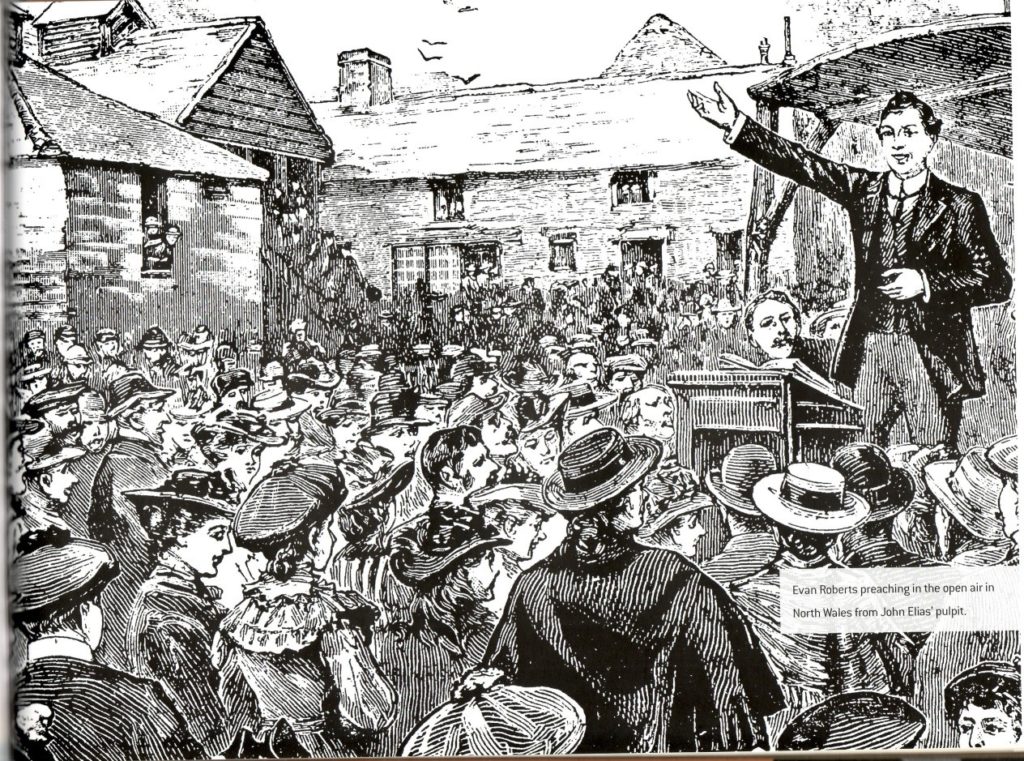

Apart from the legal aspects of committal, there were many reasons why people feared mental illness and were shamed and stigmatised by it, in a way that was not evident with any other form of illness. Individuals attracted attention when they began to behave in ways that were socially unacceptable. Committal was often precipitated by scenes of violence, destruction of clothes and property, offensive use of language, extreme and often embarrassing acts, such as outbursts of preaching in public, singing, shouting, and running naked into the street. People were diagnosed mad by their families and neighbours, because of their inappropriate and anti-social behaviour. Usually it was only then that a doctor was summoned. Some patients were admitted having first been in the workhouse, a very few came from prison, and some were apprehended by the police, either wandering insane, or for attempting suicide, or for outrageous behaviour in a public place. Therefore it was this precipitating behaviour that marked the person as insane, and which led to their committal to the asylum. They had come into conflict with the expected norms of behaviour of their society. It is this that makes the study of mental illness so different from the history of any other form of illness. We learn not only about the form of disease, but also about the social norms which were transgressed; the case papers itemise the personal, family and social conflicts, and the life events which led up to and culminated in the patients compulsory committal to the asylum.[10]

Mental illness was little understood. We still do not fully understand it today. It was feared and dreaded because recovery was unpredictable, and because for many people life would never be the same again. It is interesting that in a lecture given by Dr. R. Alun Roberts in Penygroes in 1968, based on recollections of his own experiences of being brought up in the area, he chose to refer to the alarm caused by mental illness, and the help and support required by members of the insane person’s family:

“Roedd anhwylderau’r meddwl hefyd yn achos braw a chyni yn fynych, a galw pur aml ar gymdogion i estyn help i larieiddio llid ymosodiadau disymwth a ddryswch mewn teuluoedd yn eu tro – eto yn fraw a dychryn i’r ardal.” [11]

The records of the North Wales Hospital illustrate graphically the significance of these comments. R. Alun Roberts was one of Wales’ foremost authorities on agriculture, and his intimate knowledge of the small-holding and quarrying communities of North Wales made him a fascinating and popular speaker. He had a sure grasp of the issues which affected people’s everyday lives.

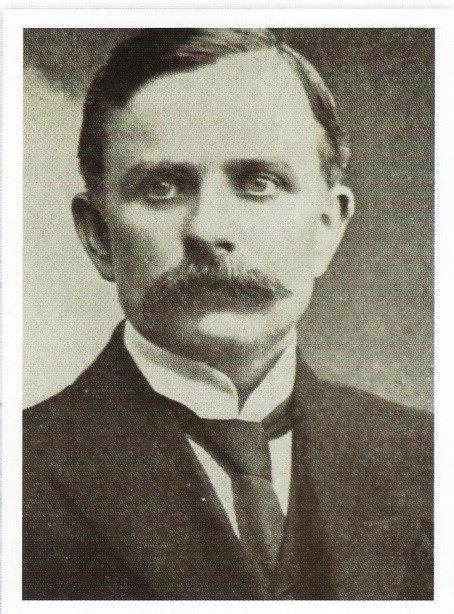

There is of course a perennial problem in researching medical history in that many causes of illness were not recognised at the time, whereas many things that we might now regard as incidental were seen as central then. Some nineteenth century doctors viewed the workings of the body as intimately connected with the health of the mind, and thus regarded constipation, for instance, as a serious disorder directly threatening the sanity of the sufferer. This diagnosis might entail for the patient a course of purgative treatment that we might consider draconian. Therefore in terms of contemporary opinion it would be significant that all of the doctors giving evidence to the Committee of Inquiry into the Conditions in the Open Quarries held in 1893, drew particular attention to the quarrymen’s habit of drinking nothing all day but stewed tea, arguing meanwhile that the high amounts of tannin resulted in a leathery lining to the stomach and severe digestive problems. Dyspepsia, asserted Dr. Evan Roberts of Penygroes, was the chief cause of disease amongst the quarrymen. During the day the men had little to eat, and only a little bread and butter before they left home in the morning.[12] John William, surgeon to the Penrhyn Quarry Hospital, argued that: “If they could provide themselves with better food in the quarry it would be better for them. The worst of it is that they take a heavy meal at night, and go to bed soon afterwards. They are subject to palsy on that account, and also congestion of the brain.”[13] In terms of today’s terminology the doctors were attributing the quarrymen’s ill-health to the ‘life-style’ which they had chosen to adopt. Dr. R.H. Mills Roberts, who was surgeon to the Dinorwic quarries and hospital, went so far as to argue that the occupation as such was “very healthy”. [14]

Displayed in the medical testimony given to this Parliamentary Committee was a tendency to blame the quarymen themselves, and also to some extent their wives, who were seen as largely responsible for the failure to provide an adequate diet. This is also true in regard to the evidence on accidents, which were portrayed as being mainly due to the negligence of the workmen, their carelessness and disregard for safety procedures. The local doctors in the quarrying areas invariably seen to have adopted this ‘personalistic’ form of explanation for the quarrymen’s ills.

A close reading of the case notes of the quarrymen sent to the asylum does reveal the extent of physical injuries endured by them, and give some indications of the psychological reactions which they might suffer. D.W. was not the only quarrymen whose physical injury had precipitated an attack of ‘insanity’. Another quarryman from Blaenau Ffestiniog, D.L., was admitted to the North Wales Lunatic Asylum in August of 1897.[15] On his committal certificate it stated that “he does not sleep and will not go to work. He talks incoherently and at times gets violent,” But the asylum doctor added the following observations: “Patient fractured his leg on the 24th December, 1896 (it was a compound fracture of the tibia). Soon afterwards a change was noticed in him and the injury is undoubtedly the cause of his mental disorder. The symptoms are now those of ordinary melancholia. He is reported to have been a steady and hardworking man.” For a person such as this the loss of mobility and of confidence associated with an injury of this type, must have made an early return to work such as quarrying, which required a high degree of physical stamina, really very daunting. Slate quarrymen began their day by descending ladders to the level of the rock faces, and ended it with climbing back up again. Throughout the day the men would work on ledges, where a stumble or a loss of balance could lead to certain death, and where blasting and falls of rock represented continuous danger. Yet clearly there was an assumption that as soon as a wound had healed the male breadwinner should resume his duties, and any reluctance to do so was viewed as shirking. The absence of any insurance, industrial compensation, or welfare state system to support the families of these victims, must have added enormously to the feelings of overwhelming responsibility. This might be expected to have a demoralising and depressive effect on men, even when healthy, or more so after suffering an accident.

D.L. was described as a man of below average height, fair development and moderately well nourished, but “low and depressed with no energy”. In the North Wales Asylum he became deluded, imagining that his wife and family were there, and hearing voices. By the following year he was reported to be in good health, eating and sleeping well and working out on the hospital farm, although he was “very reticent”. He was not discharged until 1900, aged 51, three years after his admittance.

Amongst the cases treated at the North Wales Asylum were a number of quarrymen and quarry labourers who suffered from epilepsy. This must have been hazardous not only for the man but for his fellow workers. Dr. John William told, in his evidence to the 1893 Committee of Inquiry, how he had one patient, who was subject to fits, who was in the habit of being sent into the Penrhyn Quarry Hospital “nearly every other day”. It is indicative surely, of the level of necessity that must have forced men such as this to take work in so dangerous an occupation.

Some epileptic sufferers became very violent around the period of the onset of fits. A quarryman who was admitted to the asylum in 1875 had threatened to murder his mother, and the lodgers gave testimony that he was threatening to strike them without provocation.[16] In the asylum he proved to be very quarrelsome and violent; he got into a fight with another epileptic patient whom he kicked violently in the abdomen and who died the following day from a rupture of the Ilium. After a succession of epileptic attacks, this quarryman died in the Asylum in 1878. Epilepsy was at this time still regarded as primarily a form of mental illness.

It is really quite extraordinary how some of these men managed to continue working in an industry which required so much physical stamina. Take the following examples of victims of head injuries.

R.J.R. was a 34 year old slate quarryman living at Gwastadnant, Llanberis, when he was committed to the asylum in 1891.[17] He had worked regularly at the quarry until about a fortnight before his committal, when he had become insane. It was his third attack of insanity, although this was the first time he had been sent to the asylum. He is described for us by the hospital doctors:

“Patient is a very tall man 6ft. 2ins. height and although thin is not badly built. Face pleasant but expression marred by a large scar and depression over right eye. The whole frontal eminence being as it were driven in and the site of a severe depressed fracture can be readily made out. The right eyeball more prominent that the left, and there is also considerable strabismus of same eye. He states that it was fractured at age of 14 and that he had another severe injury in same spot at 26. Shortly after injury he began to have fits but several members of his family are also epileptic. Fits average one a month but have lately become more numerous.”

R.J.R. suffered a fit shortly after his admittance to hospital and became violent and unmanageable and so was confined to a locked room. The doctor stated that the patient, when free from epileptic attack, was “an intelligent and well disposed man.. Very anxious to return home and is evidently very fond of his family.” The doctor was very anxious to see if somehow the epilepsy could be kept under control. The hospital had by now begun experimenting with bismuth as a treatment for epilepsy. The patient was discharged a couple of months after with advice from the doctor on how to cope with the attacks, and a prescription for medicine to take whenever the fits became more numerous.

The dangerousness of the occupation was common to all who worked there, and whilst many men were injured, some were killed. The Quarry Committee of Enquiry showed that in the ten year period from 1883 to 1892, there had been 110 fatal accidents in the slate quarries in Carnarvonshire. However they remarked upon the difficulty of obtaining firm statistics, and made recommendations regarding the details to be recorded in coroner’s statistics.[18] Some indication of the general incidence of accidents are to be obtained from the quarry hospitals themselves. Open any of the bound volumes of newspapers from the late nineteenth century housed in the University of Wales Bangor and you will come across references to quarrying accidents. The quarry owners and managers combed the pages of the newspapers and sought to refute any reports which they regarded as unfavourable to the quarry owners. On August 2nd, 1893, Mr. Prichard, the Working Manager to the Penrhyn Quarry, wrote to the Manchester Guardian to complain about a report published in their newspaper about an accident which had taken place at the Penrhyn quarry in which a crane had tipped over killing a workman. According to the original report a “large piece of slate rock fell from an upper gallery and threw the crane over.” Not so according to Mr. Prichard, who stated that:

“instead of a large piece of rock falling from an upper gallery, a comparatively small piece came down from a height not exceeding five feet above the floor of the gallery on which the men were working. The movement of the piece of rock was observed by the men who stood close by watching it come down; contrary to their expectation, the stone knocked over the crane, which in falling caught deceased as he was running off.”

Thus the manager and the owner sought to lay the blame squarely with the workmen.

Lord Penrhyn personally visited the scene of the accident, and he found that the fatality was solely due to the carelessness of the men composing the party, of whom one fell a victim to their own indifference to risk, and felt it his duty to inflict some punishment upon the men who were at work with the deceased in order to impress upon them, and the workmen generally, the responsibility which rests with them of taking proper precautions for their own safety and that of their fellow workmen; and it is to be hoped that the suspension of the bargain takers in question, until after the end of the next quarry month, will have the desired effect.”

Such punitive language and action displayed little in the way of sympathy for the victim. There must have been an ever present level of tension among the workmen. Many of the quarrymen who gave evidence to the Quarry Committee of Enquiry emphasised the danger of falling rocks, and stated that a simple way to reduce the hazard would be to employ men to clear the stone from the edge of the galleys periodically, and to have qualified men to inspect the workplace for safety. The system of letting divisions of the rock face to a gang of skilled quarrymen for a bargain, was conducive only to exacting the greatest possible output from the quarries, and not to ensuring safety standards. To make their bargain the men could not afford to spend time in the unproductive task of clearing waste rock, and it was said that the galleys were often strewn with debris. No doubt, as the Rev. John Rowlands observed of Welsh workers generally in 1869, the dread of illness and its consequences for families served to heighten their sense of exploitation.[19]

Faced with enormously powerful employers the quarrymen themselves could only hope to influence their conditions of work through a strong combination. Thus from the very beginnings of their unionism they had sought to enforce unity in order to gain strength. This was inevitably at the expense of any of those who did not conform, and the methods and tenacity with which not only the quarrymen but also the community in which they lived enforced sanction against them is legendary. They were labelled “cynffonwyr”, “bradwyr”, they were spat upon, refused lodging, they could not enter certain shops or pubs, and when the strikers returned to work they refused to work alongside the men who had betrayed them; there were even rumours of threatened accidents befalling the ‘blacklegs’. Much of this information has been carried in popular oral tradition, but occasionally incidents such as one in August, 1893, were reported in the newspapers. After a strike at the Llechwedd quarry, some of the men, notably those most involved in organising the strike, had not been taken back. A disturbance had broken out, and according to the report:

“ . . It appeared that a number of men attacked an old man named Hughes in an upper mill and dragged him out, attempting, it is alleged, to throw him over a precipice. Had they succeeded the man would have met with instant death, but fortunately the man slipped out of their grasp and ran for safety into the quarry office. The crowd rushed to the lower mill and seized another man named Hughes. In the meantime Mr. J.E. Greaves and Mr. Warren Roberts, as they were proceeding for luncheon to Plas Waenydd, noticed a crowd running so they turned back and arrived just in time to rescue the man out of the middle of the crowd. The man was down on the ground. He was removed to a place of safety and attended to. The two men assaulted had been working the quarry when the others had ceased.”

The intimidation experienced by blacklegs and others who refused to conform to the will of the majority, and the psychological effect which this could have upon them, is illustrated by some of the case histories of patients who were sent to the asylum.

In April, 1875 a quarryman Thomas Morris from Brynia, Bethesda was admitted.[20] On the committal papers certifying him for admission it stated that he was inattentive to his duties – also under the impression that his neighbours and fellow workmen are against him and saying that he is anxious to go to his father, sister and children who are dead. His wife testified that he had been getting up at midnight, under the impression that his fellow workmen will take him away and sacrifice him. A neighbour, Owen Thomas, had found him by the Felin Fawr reservoir, praying and saying that he was giving up his wife and children to the Lord and that his spirit would soon follow them; he was attempting to commit suicide. And another of his acquaintances, Thomas Jones, Penyffridd, had witnessed him attempting to cut his throat with a pair of scissors. The certificate was signed by Hugh Hughes, Ogwen Terrace, Bethesda. The form also tells us other information about Thomas Morris; that he had nine children of whom six were still living, the youngest of them being seven years old. His bodily health had previously been very good, the doctor stating that he had not lost a day’s work for many years. His disposition was described as sober and industrious, and he was a deacon with the Wesleyans. On his arrival at the hospital the asylum doctor was obviously concerned to establish whether or not these feelings of persecution were delusions. He clearly decided that they were not. The doctor wrote these notes on the patient’s case record:

“He exhibited symptoms of insanity for the first time six months ago. The Penrhyn quarrymen were on strike but he was one of the few who kept on working – and being greatly annoyed by the former – it preyed on his mind and produced these attacks. On admission he was extremely low and unhappy – moaning and shedding tears but perfectly rational and well aware of his condition. He said that his mind had given way and that everybody, as he thought, were conspiring against him and that he was now being punished for his sins. No delusions.”

On admittance Morris was rather thin, and so he was given quinine to improve his appetite and a draught of chloral to help him sleep, and at the end of a fortnight he was beginning to improve. On 4th May the doctor made the following entry:

“Has continued steadily to improve. He acknowledges that he has been greatly benefitted here and that it has been the means of saving his life. Was today visited by his wife and son. Is perfectly rational in his conversation and with regard to his discharge says that he will submit to the decision of the doctor.”

Morris was discharged recovered in July. The fact that he was able to recognise his own illness was a key factor in securing his early discharge. It implied that behind his acute anxiety and suicidal tendencies, was a ‘rational’ being.

In 1881 a 30 year old man from Bethesda, David Parry Jones, was sent to the asylum.[21] He had been refusing to attend his work, had not been sleeping, had been noisy and troublesome, and had assaulted his housekeeper so that she had been obliged to flee from the house in the middle of the night. Evidence was given by his uncle, John Wheldon, of Llwyn Celyn, Llanberis who stated that he “refuses to work and goes from house to house in search of a wife”. On the notes attached to the case were further details elicited from the relieving officer, and David Parry Jones’ nephew. These stated that:

“At the election of 1874 he was the only Conservative among the Quarrymen and was generally disliked by them after which he became low spirited. Subsequently a liberal union was formed among them and he refused to join and was in consequence taunted by them. He took this seriously until 3 or 4 years ago when he became excited; and he has been alternately excited and depressed ever since. He believes that all his neighbours are his enemies though this is not true – now at any rate.”

In the asylum he was found to be in rather poor health. The doctor’s case note records that he “is reserved but answers questions rationally. Says that he came here for a wife and that it is very upsetting that he cannot get one.” He was discharged the following year, and apparently returned to work, for he was still described as a quarrymen when he was re-admitted to the hospital some 11 years later, after another violent episode, this time toward his niece. On this occasion he was not discharged and remained in the hospital for the rest of his days.

Social, political and religious influences permeate the case histories of the patients sent to the North Wales Asylum during the nineteenth century.

Religious ideas and notions were particularly prevalent, religion being a dominant force in the communities which the hospital served in the nineteenth century. Biblical imagery was widespread and often exotic, with birds and creatures, as well as biblical figures such as Job, Lot, John the Baptist, featuring amongst the delusions of the insane. Patients burst into lengthy bouts of preaching, fell upon their knees in prayer, and often suffered lengthy torment under the belief that they were sinners, irredeemably condemned to suffer purgatory.

E.W, a slate quarryman from Rallt, Plas Meini, Ffestiniog was only 20 years of age when he was sent to the asylum, suffering from religious mania.[22] He was constantly muttering and praying that “the fools may be made wise” and going through gesticulations with his hands, and placing himself on his knees. He was described as an intelligent looking lad with fair complexion and hair, and pale blue eyes. On his left side, about the angle of the 8th or 9th rib was the mark of an acubrix (sic.) large and deep, caused, he said, by a fall in the quarry in which he had probably sustained a compound fracture of the rib, as this bone presented much thickening. In the hospital he desperately wanted to go home; he hoped he said to become a preacher. However he was found to be masturbating, (which was regarded at the time as almost inevitably giving rise to insanity) and also to have suppurating joints; his big toe turned gangrenous and came off. Yet at the end of the following year he was discharged to the care of his family. This frequently happened. When the patient’s family realised that the afflicted person was not going to be cured at the hospital, and that they would probably die, they preferred to take them home to allow them to spend the rest of their days in the company of their friends and relatives.

This patient was possibly suffering from tuberculosis. The incidence of tuberculosis was extremely high amongst the quarrying communities, partly the result of crowded housing conditions, poor diet, and the working conditions at the quarries. At the time a link was often made between the incidence of tuberculosis in certain families and the occurrence of insanity. Both were widely viewed as hereditary in origin until at least the turn of the century.

Some 17% of the patients admitted to the asylum between 1875 and 1914 were aged 60 years and over. Men who had survived years of hard work as quarrymen, who had brought up their families, and lived a full life, could show signs of mental illness in their declining years, and spend their latter days in the asylum. In fact men were often referred to as old, who were only in their fifties.

T.P. a 57 year old slate quarryman, of Brynhyfryd, Llanberis, who had always been regarded as steady and industrious, had been found by a neighbour on the street late in the night prior to his committal, behaving in an extremely excited manner, and using violence to anyone who approached him. He was a widower, and the father of six children, five of whom were living, the youngest being 16 years of age. Doctor W. Lloyd Williams, of Bryngwyddfan, Llanberis, wrote on the medical certificate which consigned T.P. to the asylum:

“During the last fortnight, I have observed the patient to be unnaturally talkative, going about the streets from early morning till late at night, preaching as he calls it to crowds of people. His whole conversation is irrational and at times if contradicted particularly he threatens to strike with a stick.”

In fact this man had experienced a stroke about a year previously, and had never been the same since, being described as “peevish and irritable”. On examination in the asylum he was found to have hemiplegia on the right side, though his other organs were apparently healthy. He was very confused in his ideas, preaching and discussing all kinds of schemes, and although he appeared to realise where he was, it did not seem to interest him. He was very irritable and would strike at the slightest provocation. His memory was much impaired. It was the change in behaviour that frightened and alarmed people. His son testified to his father’s behaviour being “unnatural”, and he said that he had become unmanageable. T.P. remained in the asylum for five years, until his death in 1900.

Another quarryman, aged 62 years, D.G. from Talysarn, bore the scars of two serious accidents in his working life, one to his left foot and another to his skull. The doctor noted that on examination, the “Patient is a tall elderly man, bald head and short grey whiskers. There is an old scar on his cranium and two scars on his nose – the front part of his left foot was amputated 15 years ago for an injury.” According to the local policeman Daniel had occasional bouts of intemperance. When the certifying doctor filled out the required lunacy papers, he wrote: “This man states he is possessed of property which he does not possess and that he earns enormous wages – also states that he is going to make a railway round the world, he is constantly praying and preaching incoherently.” His wife, Mary, had told the magistrates that “. .he goes into shops and orders various items that are not necessary in large quantities, such as gold watches and chains and that he threatens to strike her when opposing him.”

Obviously, when someone began to behave in ways such as this it could be an acute source of embarrassment to the whole family. According to the case notes he much resented being sent to the asylum, and denied any claim to possessing large wealth. His memory was rather poor – he couldn’t work out how long he had been in the asylum, and he claimed that his age was 79. In fact confusion over age was quite common. Shortly afterwards, this man had some sort of a seizure, and became partly paralysed, and he finally died in the hospital in May 1905. The cause of death was put down as Softening of the Brain.

Of course, problems such as dementia and other age related illnesses are no respecters of occupation, class or status. In 1877 the wife of a quarry manager was admitted to the Denbigh asylum suffering from the effects of bereavement following the death of her husband, and also from dementia.[23] She had previously been sent to the workhouse. She died in the hospital in the January of 1879. And in 1895 Dr. John William, former surgeon to the Penrhyn Quarry hospital, and authority on the health of the quarrymen, author of the pamphlet Peryglon i Iechyd Y Chwarelwyr, was admitted as a private patient to the asylum. This, unlike a pauper committal, required evidence from two separate medical authorities. Here is the evidence recorded by the second of the two certifying doctors Dr. Arthur Hughes of Barmouth:

“Incoherency, is under many delusions such as believing that he is at home in practice at Bethesda, that his two thighs are dislocated, that he goes out fishing and takes hundreds of trout daily. He has the appearance and habits of an insane person and cannot sustain unbroken conversation for any length of time.” [24]

A few notes were added to his case history at the asylum, to the effect that:

“This patient has been a surgeon to the Penrhyn Quarries for many years. He married for the second time some years ago a woman many years his junior. Soon after this he is said to have become intemperate. He gave up his quarry practice some time since and was engaged in private practice until 9 weeks ago when he became insane. A month ago he went to live with his sister at Dolgelley but has steadily become worse.”

In the hospital John William appears to have been totally disoriented and was ‘full of all sorts of delusions’. In 1897 a case note records:

“Same in every way, as deluded as ever, owns Merionethshire a present from the Queen. Is having a palace and hospital built with about 1,000 beds and he is going to be the head surgeon. Has married the daughter of the Tsar of Russia, whom he has delivered of a child. A very jolly old fellow, in good health.”

The case notes tell us that he ate and slept well, and seemed perfectly content, although his delusions were “too numerous to mention”. He finally died of pneumonia in 1909.

It would be misleading to suggest that all cases followed on from some bodily ailment, or injury, or arose from incapacity or old age. Sometimes the onset of insanity could be startling and unpredictable. Lewis Davies was lodging at the same address, 33 Glynllifon Street, Blaenau Ffestiniog, as Evan Williams, and testified that the latter went out at 12.00 o’clock noon, and seemed rather in an excited state, and went on to the top of the Mountain close by, and very suddenly undressed perfectly naked, and ran about for miles.[25] He was said to be continually talking incoherently about religious matters – he claimed that he had at last seen Satan – and was continually repeating this all day. On admission to the asylum, in January, 1890, he was described as a strongly built, respectable looking fellow, but on the first night he was violent and struggling and had to be put in the padded room. He then quietened down, and over the next fortnight showed some improvement. But on February 11th, the case note records, he “unfortunately relapsed and is now in an acutely maniacal condition, and during the last 2 days has been confined to the padded room. Refuses all food – and have had to give it to him forcibly with teapot.” He did however once again improve, and was finally discharged recovered in 1891. Force feeding of patients occurred fairly frequently, and was regarded within the hospital as an effective means of dealing with cases of self-starvation. There seems to have been no attempt during these years, either by the doctors or anyone else, to question its moral efficacy.

The behaviour of the insane is often colourful and bizarre, and some cases must certainly have made a dramatic impression on passing observers. In 1879 a slate quarry labourer from Penmachno, Richard Richards was admitted to the asylum.[26] He had been out of work for three months but a fortnight previously had got a job. He was said to have over exerted himself, and on the fifth day he drank a considerable quantity of whiskey, soon after which he had jumped out of bed shouting that he was murdered, and was taken to the police station, and after which he gradually became worse. It appears that he was taken to the workhouse, because it was there that the certifying doctor filled out the forms securing his transfer to the asylum:

“Swearing. I have heard him saying that he will save us all from everlasting punishment. He was boring a hole in the wall pretending to be blasting. Shouting terribly all kinds of nonsense. I am a bull and that he was Joseph Thomas of Carno. (A famous preacher of the time.) He was also climbing up the workhouse gate calling himself Jesus Christ.”

Around the same time a 35 year old quarryman from Mynachlog in Ffestiniog began to act in strange ways, saying that he possessed large sums of money and demanding to search the neighbours’ houses for it, at the same time blacking his face imagining himself to be a Christy minstrel.[27] He too was sent to the asylum.

In 1880 another quarryman from Ffestiniog fancied that he had wires going through his bowels, and that people were intending to cause him injury.[28] But the hospital doctor soon recognised the symptoms – the thick and drawling speech, and feeble and unsteady gait signified that he was suffering from General Paralysis of the Insane, the tertiary stage of syphilis, for which there was no cure. At the time the connection between General Paralysis and syphilis was not sufficiently understood, and the ‘supposed cause’ of his illness was put down as ‘anxiety of mind’.

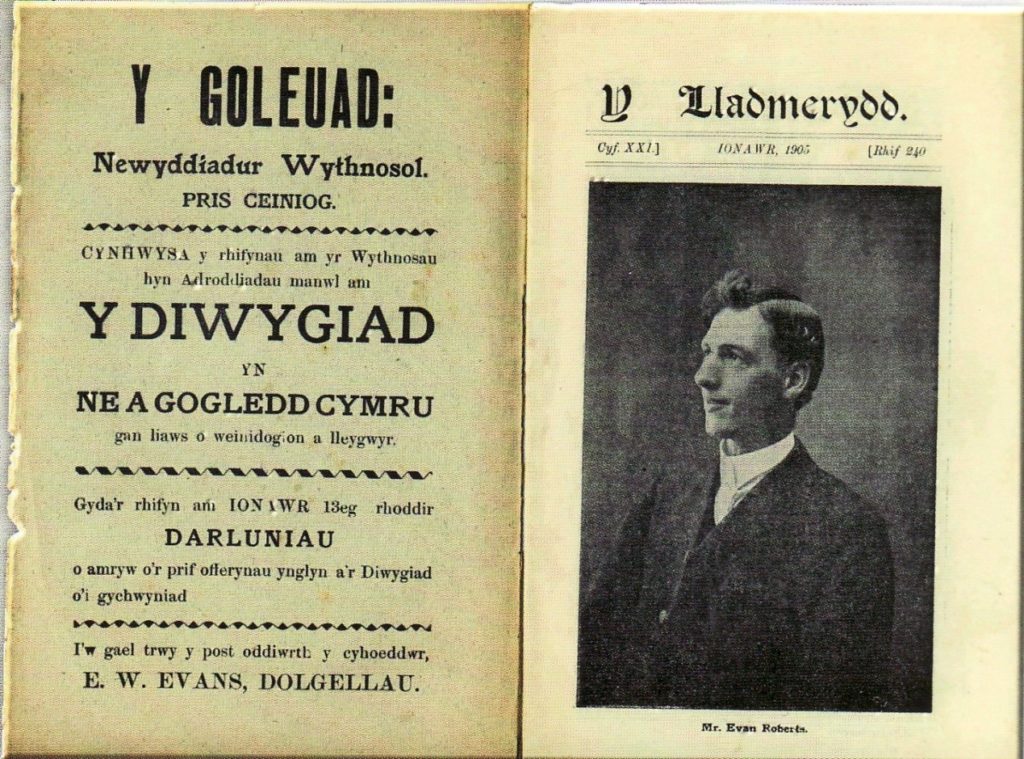

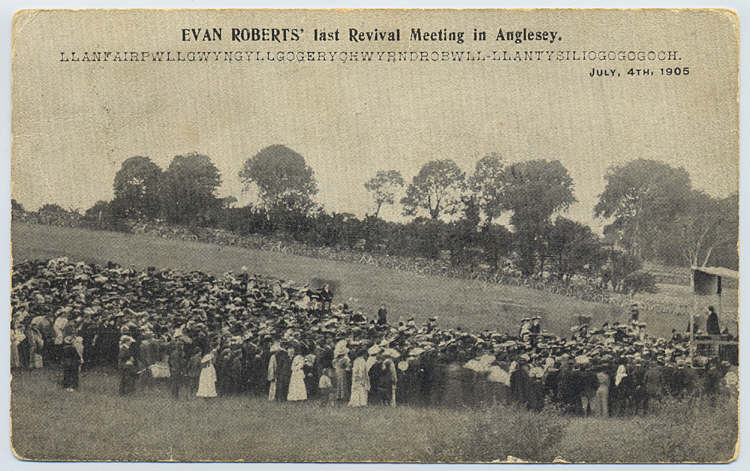

All forms of mental illness were frightening to the relatives. But happily not all ended in tragedy. In fact about 35% of all patients committed to the hospital were discharged cured within 12 months, some in far less. In 1905 a 20 year old quarryman insisted that he saw the Holy Ghost in the form of smoke, changing to the shape of a dog; his manner, conduct and language were totally at variance with his usual habits.[29] He had always been a quiet, and steady young man until he began to take an active part in the Religious Revival meetings, when some change in his behaviour was noticed. Once in the asylum he rapidly improved and within a month he was discharged cured.

Finally, the case of Griffith John Griffiths, a 26 year old quarryman from Pentre, Llanllyfni, admitted to the asylum in 1878, in a feeble condition, and suffering from Acute Mania.[30] The evidence adduced on his committal certificate states: “Entire change of character. Loss of memory. Talks about deceitfulness of parents. Obscene language and wants women in his bed with him.” He had apparently become strange in his manner and behaviour some four to six months ago, becoming low spirited and sometimes not speaking for hours together. He did not work for a month, and then went to work for a fortnight but gave up in the same space of time. Now he was not so low spirited but had become noisy and abusive and it was said that he “rambles about shouting”. On his arrival at the asylum it was noted that he was “slight and spare – eyes blue – pupils dilated – complexion pale – hair dark, slight moustache. He was talking and shouting in high spirits, and still wanting women.” He was given plenty of sedatives and purged, and then allowed to feed himself up on plenty of food. His bodily health improved, and he became quieter, and grew stronger, but remained very simple and childish; and he was discharged in November of the same year. However in October 1881 he was once again committed to the asylum, after endeavouring “to throw several of his fellow-workmen to the Quarry, a depth of over one hundred yards”. The asylum doctor observed what appeared to be a slow degeneration of the brain, and the patient thereafter remained in the asylum until his death in 1906.

The foregoing cases serve to illustrate the wide variety of symptoms, in terms of behavioural patterns, which could be perceived to constitute mental illness. They enable us to appreciate how such “ymosodiadau disymwth” (disturbing attacks) would indeed cause “braw a chyni yn fynych” (terror and anguish frequently). It is easy to understand why such events are so rarely spoken of or written about by victims, families or associates. The records preserved at the archives in Ruthin enable us to re-explore this opaque area of history, and hopefully by naming make familiar, and thus less strange and threatening to us all.

ur initial attempts to utilise the records of the North Wales Asylum assuredly validate two sets of contentions. Firstly that of a group of scholars who have become explorers of the “underside of society”, who contend that the investigation of the submerged, the outcast and the deviant impells us toward a fuller appreciation of the taken-for-granted aspects of the so-called “normal”.[31] Secondly, that of C.Wright Mills “. . . that the biographies of men and women, the kinds of individuals they invariably become, cannot be understood without reference to the historical structures in which the milieux of their everyday life are organised”.[32] Inscribed in most of the records of the asylum patients are clues to domestic relationships and normative patterns in communities. Those of individuals from some distinctive occupational groups potentially provide much more as we begin to chart their very direct linkages to capitalist enterprise, and to collective responses to economic exploitation.

Dr. Pamela Michael

Footnotes

[1] Denbighshire Archives, Ruthun, HD/1/365 Case no. 4004, date of admittance 13/9/1888

[2] Porter, Roy A Social History of Madness, 1987, George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd., London.

[3] Szasz, Thomas The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct Dell, New York, 1961.

[4]Lindsay, Jean A History of the North Wales Slate Industry, David and Charles, Newton Abbott, 1974, pp.234-242; Jones, Emyr Canrif y Chwarelwyr, Gwasg Gee, Denbigh, 1964; Jones, Emyr Bargen Dinorwig, Ty ar y Graig, Caernarfon, 1980; Jones, R.M. The North Wales Quarrymen, 1874-1922, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1981.

[5] Jones, R. M. The North Wales Quarrymen, 1874-1922, op.cit. p.35.

[6] ibid. p. 34.

[7] There are two serious problems in analysing the statistics. Firstly, the decennial Census of Occupations records the numbers working in ‘mines and quarries’. There are far fewer miners than there are quarrymen admitted to the hospital, so whether the one is over-represented at the expense of the other is difficult to ascertain. Quarrying predominated in the western counties of North Wales, mining in the east. It may be that the relieving officers, the key persons responsible for arranging a legal ‘certificate of lunacy’ which would dispatch the patient to the asylum, were more active and responsive to problems identified as insanity amongst the quarrymen of Carnarvonshire, than their counterparts amongst the miners of Flintshire. Hence a difference in referrals would not necessarily imply a difference in incidence. Secondly, the asylum, did not follow the same rules of recording occupations as the census enumerators. They relied on self-reportage, or on the word of family or relieving officer. Therefore if a man referred to himself as a ‘labourer’ then he was recorded as such on the admissions papers to the hospital, even though he may have been a labourer in the quarries.

[8] Report of the Quarry Committee of Inquiry, 1893; Report of the Departmental Committee upon Merionethshire Slate Mines, 1895.

[9] Prichard, Caradog Un Nos Ola Leuad, 1988, Gwasg Gwalia, Caernarfon.

[10] Voluntary admissions did not occur until after the passing of the 1930 Mental Treatment Act.

[11] Roberts, Robert Alun Y tyddynnwr chwarelwr yn Nyffryn Nantlle: atgotion am Ddyffryn Nantlle, Caernarfon: Llyfrgell Sir Caernarfon, 1969, (Darlith Flynyddol Llyfrgell Penygroes, 1968.)

[12] Report of the Quarry Committee of Inquiry, 1893, evidence of Dr. Evan Roberts, par. 73-82

[13] ibid. evidence of Dr. J.William, 265

[14] ibid. statement of Dr. Mills Roberts, p.24. Although interestingly Dr. Mills Roberts was to establish his medical career on the basis of publications relating to cases of head injuries treated by him at the quarry hospital, e.g. see British Medical Journal, August 15, 1903 ‘Dinorwic Quarry Hospital: cases of head injury . .’; also for treatment of other accidents reported by him in Transactions of the Clinical Society of London, vol. 30.

[15] Denbighshire Record Office HD/1/370, Case no. 5271, date of admission 23/8/1897

[16] ibid. HD/1/360 Case no. 2427, date of admission 20/2/1875.

[17] Denbighshire Record Office, HD/1/365 Case no. 4262, date of admission 15/1/1891

[18] Report by the Quarry Committee of Inquiry, December, 1893, London, p. iv, Appendix II, p. 4-5, and evidence of Dr. William Ogle, p. 77-84.

[19] cited in Jones, I.G. ‘The People’s Health in Mid-Victorian Wales’, Mid-Victorian Wales: The Observers and the Observed, 1992, Cardiff, University of Wales Press, p.48-9, and footnote p.176.

[20] Denbighshire Record Office HD/1/360 Case no. 2441, date of admission 16/4/1875

[21] Denbighshire Record Office HD/1/361 Case no. 3059, date of admission 5/2/1881

[22] Denbighshire Record Office HD/1/360 Case no. 2614, date of admission 30/9/1876

[23] ibid. HD/1/360 Case no. 2692 date of admission 31/7/1877

[24] ibid. HD/1/368 Case no. 566, p. 122 (private patient) date of admission 23/4/1895

[25] ibid. HD/1/365 Case no. 4143, date of admission 11/1/1890

[26] ibid HD/1/361 Case no. 2851, date of admission 11/2/1879

[27] ibid. HD/1/360 Case no. 2541, date of admission 13/3/1876

[28] ibid. HD/1/361 Case no. 3041, date of admission 9/12/1880

[29] ibid. HD/1/374 Case no. 6531, date of admission 7/3/1905

[30] ibid. HD/1/360 Case no. 2769, date of admission 8/5/1878

[31] Most notably Erving Goffman and Richard Cobb, and many students of deviancy from Durkheim onwards.

[32] Mills, C.W. The Sociological Imagination, New York, OUP, 1968.